NEW REPUBLIC, ALEX SHEPHARD

Joshua Green’s Devil’s Bargain is pitched as a book about Steve Bannon, the former Breitbart News executive chairman who is now chief White House strategist, but it isn’t a biography per se.

The now-familiar checkpoints of Bannon’s life—his working-class roots and Catholicism, his stints in the Navy (the source of his Islamophobia) and Goldman Sachs, and his stewardship of Breitbart—are mere fodder for an inevitable ending: the election of Donald Trump

Which is to say that Devil’s Bargain is really a campaign book.

Devil’s Bargain argues that... Trump’s victory would not have been possible without Bannon. It was Bannon who brought decades of anti-Clinton knowledge and connections when he took over the Trump campaign and guided it through its burn-everything-down final act.

The deciding voters in the 2016 election mostly broke toward Trump in the last two weeks, following the now infamous letter from then-FBI Director James Comey that resurrected Clinton’s email scandal. Trump’s data team, Green reports, labeled these voters “double-haters” who despised both candidates equally. However, if the Comey letter ultimately gave these voters the reason they needed to vote against Clinton, Devil’s Bargain shows that the plot to make Clinton look unviable went back decades.

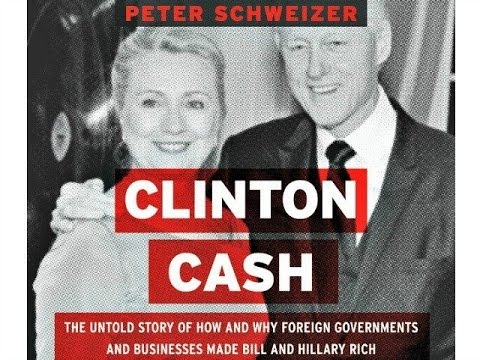

Bannon is notably not one of these career anti-Clinton fighters. But he did found the Government Accountability Institute, a think tank that existed to fund Peter Schweizer, the author of Clinton Cash. Bannon’s key insight was that the sheen of respectability goes a long, long way. Bannon fed Schweizer’s controversial, often flimsy findings to major outlets like The New York Times, making Clinton’s alleged corruption and

untrustworthiness a legitimate target for inquiry rather than a font for conspiracy theories.

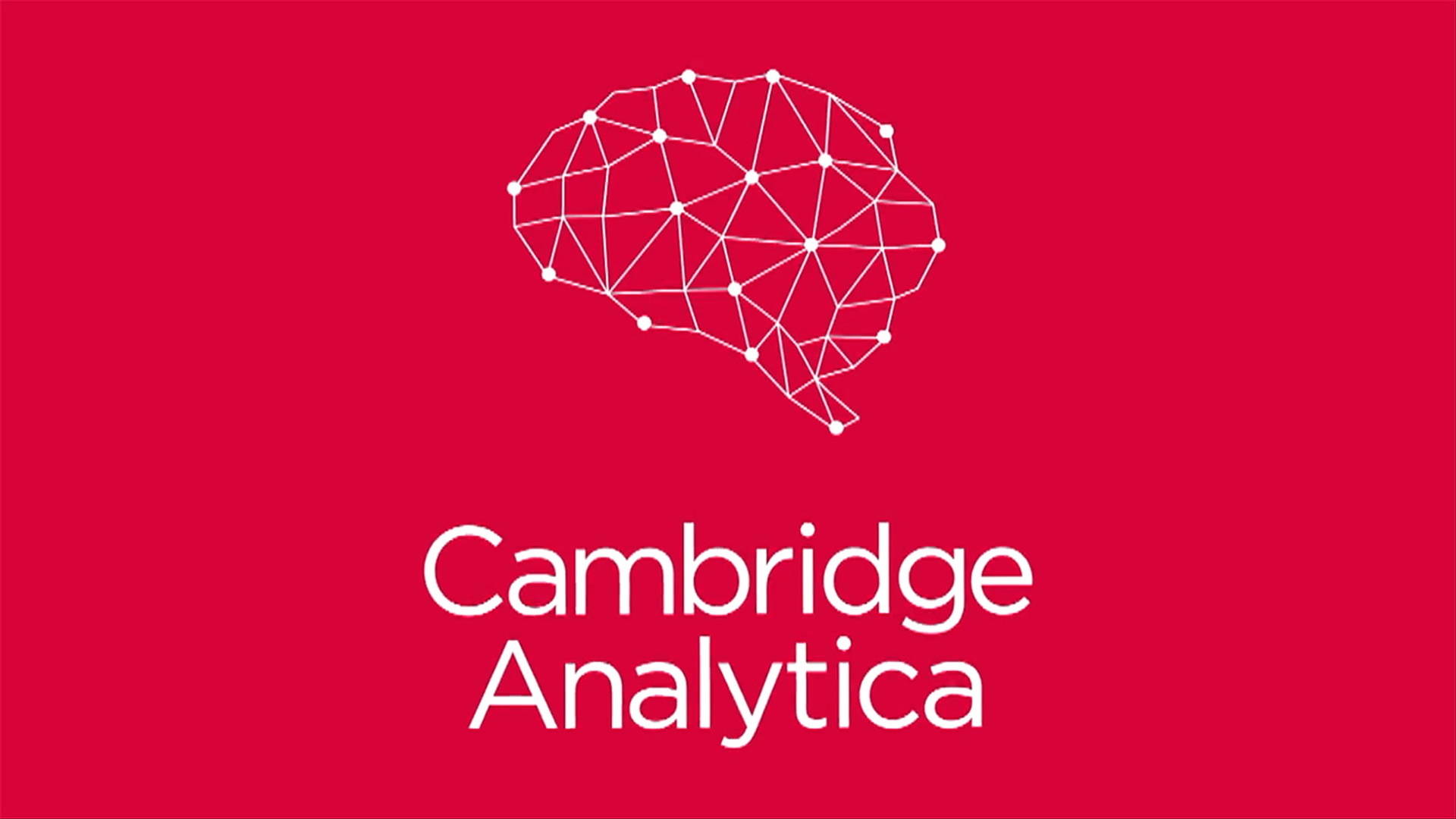

The Government Accountability Institute, Green writes, was only one cog in a machine built to bring Clinton down. There was also Breitbart News, where provocateurs like Milo Yiannopoulos fed raw meat to a rabid anti-Clinton, anti-globalist, anti-SJW [SocialJusticeWarriors], and Islamophobic base; Glittering Steel, where Bannon made Leni Riefenstahl-ish movies about the corruption of the Clintons and the need for populist outsiders; and Cambridge Analytica, the data firm that helped bring us Brexit and that could provide sophisticated analysis and targeting to campaigns like Trump’s. The Mercers funded all of these entities, and Bannon was involved with every one of them except Cambridge Analytica. “By the time Clinton launched her presidential campaign in 2015,” Green writes, “all four of these groups were up and running like the machine they were envisioned to be.”

|

| Robert Mercer, Trump supporter and owner of Cambridge Analytica. Photograph: Rex |

Because Trump’s victory was so unexpected, his success has often been rooted in the force of his personality. “If I didn’t come along, the Republican Party had zero chance of winning the presidency,” Trump told Green in 2016. Nothing in Devil’s Bargain contradicts that claim, but Green argues that it was only by fully embracing Bannon’s white nationalist worldview and his win-at-all-costs anti-Clintonism that he could have won the presidency.

| Drawing by John Spring |

Only someone with his and Bannon’s transgressive instincts, along with their seeming incapacity for moral and intellectual embarrassment, could have defeated the well-oiled if soulless machine that was Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign.

---

They also grasped that much that was supposed to matter in politics no longer did — detailed policy papers, for instance, or personal decorum. Trump, Green writes, “figured out that the norms forbidding such behavior were not inviolable rules that carried a harsh penalty but rather sentiments of a nobler, bygone era, gossamer-thin and needlessly adhered to by politicians who lacked his willingness to defy them.”

Republican political operatives had spent the Obama years wondering about the “missing” white voters who had failed to show up for John McCain and Mitt Romney. Turns out, they (or others like them) were online, and Bannon — whose own fantasies were suggested by a portrait he had of himself in his office, dressed as Napoleon — was proposing to supply this army with the necessary ammunition.

Much of it would come from the bile factory at Breitbart News. Another part would be supplied by the Government Accountability Institute, a Tallahassee, Fla.-based nonprofit that mined the “deep Web” and dug up the dirt on the Clinton Foundation for Peter Schweizer’s 2015 blockbuster “Clinton Cash.”

A data-analytics firm, Cambridge Analytica, an offshoot of a British company “that advised foreign governments and militaries on influencing elections and public opinion using the tools of psychological warfare.”

A data-analytics firm, Cambridge Analytica, an offshoot of a British company “that advised foreign governments and militaries on influencing elections and public opinion using the tools of psychological warfare.”

What all of this added up to was a kind of alt-G.O.P. — agile and indifferent to norms and boundaries — that could supply the Trump campaign with everything it needed to win.

|

| Illustration: James Melaugh |

Bannon is by upbringing and temperament a son of the embattled South, a working-class Catholic who grew up in Richmond, Virginia, when the state was still a backward fief, ruled by Senator Harry F. Byrd Jr., an early leader of Southern “massive resistance” to civil rights. From the start, Bannon seems to have been a younger version of Pat Buchanan: a noisy, brawling, bred-in-the-bone anti-Communist. Educated by Benedictines at a Catholic military school, he went on to Virginia Tech and then enlisted in the Navy in 1977. He was a navigator on a destroyer in the North Arabian Sea in 1980 when the Carter administration was putting the last touches on its disastrous secret mission to free the Iran hostages.

His hatred of the weakling Jimmy Carter soon transubstantiated into trembling worship of Ronald Reagan. Bannon had the fanatic’s insatiable need to find, or invent, cartoon heroes and heavies. But he also had a quick, absorptive mind. Enrolling in the Harvard Business School at twenty-nine, he outperformed his younger classmates but remained rough around the edges and was lucky to land at Goldman Sachs in the Gordon Gekko era.

Like Trump, Bannon gravitated to media—not in Manhattan, but in Hollywood. Goldman Sachs sent him there in 1987, when studios were being bought and rebuilt, like real estate tear-downs, attracting all manner of hucksters. Bannon was an ambiguous player in this murky world. Today the best-known item in his growing legend—first reported by Green in his 2015 profile—is that he gets a handsome income in residuals from Seinfeld; it was included in a package of TV shows he got a stake in as part of a financing deal. Seinfield, of course, became a colossal hit, and Bannon’s payout has been estimated to be as much as $32 million. Connie Bruck dug into this claim for The New Yorker and found no solid evidence for the Seinfeld payout—and much skepticism on the part of people close to the show.

But Hollywood financing is complex. Devil’s Bargain reveals that Bannon does get Seinfeld residuals, though the amount is far smaller than what has been reported; according to Green, on his White House disclosure statement Bannon listed the figure as “$2 million and counting.” It is a measly sum by Hollywood standards and supports the testimony of movie-business sharks who have little memory of Bannon. “I never heard of him, prior to Trumpism,” the media tycoon Barry Diller has said.

Green, more generously, describes Bannon’s Hollywood season, and his various other adventures, as preparing him for his true vocation as ringmaster of the new, Trump-led right. Bannon’s talent, like Trump’s, is finding and picking up the strains of hidden grievance: against “media elites,” feminists, civil rights activists, left-wing professors, and, above all, immigrants.

----

In Hong Kong, where Bannon went in 2005 to put together a licensing deal involving the video game World of Warcraft, he discovered the teeming community of gamers, millions of “intense young men…who disappeared for days or even weeks at a time in alternate realities.” He sensed “the powerful currents that run just below the surface of the Internet,” Green writes, and “began to wonder if those forces could be harnessed and, if so, how he might exploit them.”

By this time, Bannon was also producing and writing political films of his own—crude armies-of-the-night clashes that were frankly modeled on Leni Riefenstahl: the gathering storm, the threat of violence, the Wagnerian soundtracks, the “technique of fear,” as his longtime screenwriting partner told Connie Bruck.

Bannon’s first film, In the Face of Evil, which glorified Reagan’s part in winning the cold war, left reviewers cold—“very much like Soviet propaganda,” one wrote. But it thrilled a small but intense contingent of Hollywood conservatives.

Since the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, animus had been building against the big studios, “so non-understanding of normal human Americans,” as Peggy Noonan said at the time. In December 2004, Bannon and others, “peasants with the pitchforks storming the lord’s manor,” as he told a New York Times reporter, congregated at an event called the Liberty Film Festival. After one screening Bannon was crushed in a bear hug by the online provocateur Andrew Breitbart, “squeezing me like my head’s going to blow up and saying how we’ve gotta take back the culture.”

| Andrew Breitbart speaks at a 'Cut Spending Now' rally at the conservative Americans for Prosperity 'Defending the American Dream Summit.' NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images |

Breitbart wasn’t yet the “pirate king” of the new tabloid right that was forming on the Internet. The title still belonged to his mentor and longtime boss, Matt Drudge, the Walter Winchell of Internet gossip, complete with rakishly tipped fedora....Drudge, Breitbart, and Bannon are routinely depicted as wild-eyed extremists. ...they spoiled for a Day of the Locust showdown with the Lotus Eaters in Hollywood and inside the Beltway, a heroic purging of the sewage pipes, concocted a kind of political porn—gossip and exposé commingled with conspiracy. There is a long half-forgotten history of this on the right dating back to McCarthy-era best-sellers like Washington Confidential (1951), which mixed sleazy tidbits (the actual telephone numbers and street addresses of prostitutes) and warnings that, despite McCarthy’s hosing the stables, the Pentagon and State Department were infested with Communists and “fairies.”

|

| “Washington Confidential” claimed to be an inside look at crime, graft and scandal in the nation’s capital. (Collection of John Kelly) |

----

Bannon, still making movie paeans to emerging political stars on the right (Sarah Palin was another subject), had yet to grasp the most important lesson of tabloid politics. It works best as a form of attack. And an inviting target was already there. One of Bannon’s collaborators, David Bossie, was a Clinton hater whose excesses had gotten him fired from the congressional committee investigating Whitewater.

| David Bossie |

Through his organization Citizens United Productions, Bossie produced Hillary: The Movie in time for the 2008 primaries, but the Federal Election Commission restricted its advertising on the ground that it was plainly opposition propaganda. Bossie protested that this was an infringement of his First Amendment freedoms, and eventually the dispute reached the Supreme Court, which in 2010 ruled in his favor. The Citizens United case shattered the rules on campaign spending and began the unlimited flow of money into politics.

|

| A poster for Hillary: The Movie. |

In 2011, Bossie took Bannon to Trump Tower to meet Donald Trump, who was thinking of running for president, and the chemistry was immediate. Unlike the political professionals, Bannon, like Trump, was “fluent in the argot of Wall Street and Hollywood,” Green writes. But at the same time, in his disheveled eccentricity, he posed no “alpha male” threat. Thereafter, at conservative events, Trump sought out Bannon, asking, “Where’s my Steve?”

|

Cohn approaches his Bentley, 1977.

By Neal Boenzi/The New York Times/Redux.

|

...Trump saw politics not as a form of entertainment but as pure entertainment aimed at specific audiences and markets. He also knew a good deal about tabloid politics. His tutor was another down-market genius, Roy Cohn, the lawyer and former counsel for Joe McCarthy.

| National-Enquirer-26-December-2016_01-519x600-1056342.jpg |

Already in the 1990s, according to a recent account in The New Yorker, Trump had entered an alliance of sorts with The National Enquirer, transforming from a subject of its scurrilous headlines into a “source” for salacious stories on others; during the 2016 campaign the Enquirer became one of Trump’s strongest mouthpieces. But it was Trump’s TV series The Apprentice that elevated him from Page Six to weekly living room fixture, with his arch bombast and casino bluster. In its first season, in 2004, the show drew an average audience of some 20 million viewers. (By comparison, in 2016 the first Republican debate, which set a record, drew 24 million. All the rest drew many fewer. The Democratic debates got puny audiences, sometimes of 5 million.) No candidate since Ronald Reagan had entered politics as well known as Trump.

The Apprentice was an ideal launching pad for a second reason. It included black contestants in power suits, taking their place at the Trump Tower conference table for the end-of-show drubbing from the egalitarian boss, who also dispensed “insider” wisdom. It was an attractive way for Fortune 500 companies to reach minority consumers with the message that you could find nonwhite faces in corporate boardrooms. Actually there were very few such faces, and hardly any in Trump’s own company. But...According to private demographic research conducted at the time,” Green reports, Trump “was even more popular with African-American and Hispanic viewers than he was with Caucasian audiences.”

[But, in 2011, Trump leapt on the race-tinged “birther crusade” against President Obama....Why,...Green asks, did Trump needlessly “torch his relationship with minority voters”?

| Donald Trump and Randal Pinkett in 2006. Bennett Raglin/WireImage.com |

One answer is that Trump, the enlightened boss, was a fake, and his show a Potemkin village. Randal Pinkett, an African-American Rhodes Scholar who won The Apprentice competition in its fourth season, spoke out against Trump during the election, saying that Trump made racist comments to him and tried to talk him into sharing the victory with a white female runner-up. Pinkett has also said that when he joined the Trump organization—his prize for winning the competition—“I never sat in a room with another person of color over my entire year there.” For Trump, it appears, ideas about race aren’t fixed beliefs, but movable parts of the scenery.

| Robert Mercer and his daughter Rebekah Mercer attend the 2017 TIME 100 Gala on April 25, 2017 |

----

Green shrewdly sees a second motive for Trump’s clinging to the birther fantasy: it tapped into a huge new constituency. In his transactional world of “commutative property,” Trump had traded one audience for another. His canny insight—or instinct—was to understand that the Republican nomination would go to the candidate who traveled the farthest downstream, not just to viewers of Fox News but to the audiences who tuned in to conspiratorial talk radio and drew their news from customized Internet feeds and social media.

In early 2012, Bannon had been helping Andrew Breitbart raise capital for a relaunch of his site and secured $10 million from the hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer and his daughter Rebekah—“the alt-Kochs,” Green calls them. But in March of that year, Breitbart dropped dead of a heart attack on a sidewalk in Brentwood, at age forty-three. At Breitbart’s funeral, Bannon told Drudge he was going ahead with the relaunch and would be in charge himself. He had the blessings of the Mercers.

He had a new theme, the perils of immigration, one component of his populist nationalism and its hatred of “secular” globalist “elites.” Again Washington Confidential is a useful guide. Its authors told lurid stories of a crime- and sex-crazed black population, growing but half hidden, which set upon white citizens and the police, who were powerless to make arrests and get convictions because of liberal politicians and judges. Bannon updated this case in Breitbart, only now the threat came from lawless immigrant hordes streaming across the border into “sanctuary cities,” where they committed crimes, including murder and rape, and again went unpunished. In 2013, Bannon set up a Breitbart bureau in Lubbock, Texas, to report on this. He also got to know border agents. Many of Trump’s slurs against Mexican immigrants came from them, Green reports, and for the like minded had the ring of the truth at last being spoken by a candidate unafraid to defy political speech codes.

----

[Washington Confidential presented two useful lessons: One: if you have the dirt, go with it. The second was, if you don’t have it, make it up, since “narrative truth” outweighed “factual truth,” as a former Breitbart writer later explained.

[Breitbart followed these precepts when he] posted on one of his websites a video of a speech to the NAACP by Shirley Sherrod, a Georgia official in the US Department of Agriculture, in which she seemed to say she’d discriminated against a white farmer. The video cost Sherrod her job even though it turned out to have been ruthlessly doctored. This was too much even for Fox News, which had broadcast Breitbart’s edit of the video and was now under attack. Breitbart was banished from respectable conservative precincts, only to redeem himself a year later by breaking the story of Anthony Weiner’s salacious tweets.

----

....Green asserts, with a good deal of supporting evidence, that from the beginning the election was less about Trump—a “blunt instrument for us,” as Bannon said—than about Clinton. Another of Bannon’s projects was setting up an operation, the Government Accountability Institute, in Tallahassee, which produced anti-Clinton literature—not Drudge-style leaks, but carefully planned lines of attack, “storyboarding it out months in advance.”

The Government Accountability Institute,s great product was a book, Clinton Cash, a muckraking exposé on the Clinton Foundation by Peter Schweizer that had just enough substance for wide circulation.*

Bannon took the findings, including Bill Clinton’s contacts with foreign governments while Hillary Clinton was secretary of state, to The New York Times. It was his deftest stroke. With his businessman’s knowledge of media finances he knew newspapers were struggling. Advertising revenue was shrinking, and newsrooms could no longer afford to invest money and staff on a secondary investigative story like the Clinton Foundation. The paper had already been partnering with nonprofit newsrooms like ProPublica. Bannon also knew that reporters, while often liberal, aren’t ideological. They want good stories, just as Drudge and Breitbart did, even if they adhere to much more scrupulous standards. Indeed, there were questions to be raised about the Clinton Foundation, though nothing illegal was turned up, in contrast to the Trump Foundation, whose glaring tax avoidance shenanigans got little attention in the press. To Clinton supporters, it gave new credibility to the “vast right-wing conspiracy,” as Hillary Clinton had called it in 1998.

....and Trump’s 2016 victory was its most bountiful harvest. The crowning evidence came during the final months before the election, when Rebekah Mercer told Trump he should formally appoint Bannon to run the campaign he had hitherto been advising from the sidelines—and not just Bannon, Mercer suggested, but also the pollster Kellyanne Conway, whose history of Clinton-bashing dated back to the 1990s. Conway’s husband, George Conway, had been Paula Jones’s lawyer in her sexual harassment suit against Bill Clinton. David Bossie also joined, as Conway’s deputy.

In early October, after the Access Hollywood video showing Trump’s lewd boast about sexual assault was leaked to The Washington Post, Bannon mounted the tu quoque counteroffensive, with appearances by Jones and others. Andrew Breitbart also contributed, from beyond the grave. His revelations about Anthony Weiner had started another trail of investigation, and it got tangled with the election when the FBI director James Comey rashly said the bureau had captured e-mails on the computer of Weiner’s wife, Huma Abedin, a member of Clinton’s inner circle, that might relate to the FBI’s investigation of Clinton’s use of a private e-mail server when she was secretary of state. Clinton has said this last October surprise cost her the election. Green reports that the Trump campaign’s own “data analytics” registered a sharp break toward Trump at exactly that time.

----

But if Trump is easily distracted, Bannon is not. Green’s book is in part a cautionary tale: both Trump and Bannon have a history of being taken lightly only to rear up and catch the skeptics by surprise. Bannon was scoffed at in Hollywood, and in the early stages of the election he seemed no match for Roger Ailes. Most thought Trump would be laughed off the stage once the votes were counted. Those assumptions are now haunting memories. Bannon is still with us, [albeit no longer in the Oval Office] and for the time being his “blunt instrument” is still in the White House.