Born in Depression-era Brooklyn, Justice Ginsburg excelled academically and went to the top of her law school class at a time when women were still called upon to justify taking a man’s place. She earned a reputation as the legal embodiment of the women’s liberation movement and as a widely admired role model for generations of female lawyers.

Working in the 1970s with the American Civil Liberties Union, Justice Ginsburg successfully argued a series of cases before the high court that strategically chipped away at the legal wall of gender discrimination, eventually causing it to topple. Later, as a member of the court’s liberal bloc, she was a reliable vote to enhance the rights of women, protect affirmative action and minority voting rights and defend a woman’s right to choose an abortion.

On the court, she became an iconic figure to a new wave of young feminists, and her regal image as the “Notorious RBG” graced T-shirts and coffee mugs. She was delighted by the attention, although she said her law clerks had to explain that the moniker referred to a deceased rapper, the Notorious B.I.G. She also was the subject of a popular film documentary, “RBG” (2018).

When she was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in 2015, her colleague and improbable close friend, conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, wrote about her dual roles as crusader and judge. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg has had two distinguished legal careers, either one of which would alone entitle her to be one of Time’s 100,” wrote Scalia, who died in 2016.

After Scalia’s death, the Senate took no action to confirm President Barack Obama’s nominee to the court, U.S. Appeals Court Judge Merrick Garland. President Trump, who took office in 2017, has nominated two new justices to the court, Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh, the latter succeeding Justice Anthony M. Kennedy.

NPR reported that Justice Ginsburg, in a statement dictated to her granddaughter in recent days, said, “My most fervent wish is that I will not be replaced until a new president is installed.”

A landmark moment for Justice Ginsburg came in 2011, when the court for the first time opened its term with three female justices. Justice Ginsburg said in an interview with The Washington Post that it would “change the public perception of where women are in the justice system. When the schoolchildren file in and out of the court and they look up and they see three women, then that will seem natural and proper — just how it is.”

Her outspoken feminism played a role in Justice Ginsburg’s success. President Bill Clinton acknowledged that in 1993 when he nominated her to replace retiring Justice Byron White. At the time, she was a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

“Many admirers of her work say that she is to the women’s movement what former Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall was to the movement for the rights of African Americans,” Clinton said in Rose Garden ceremony. “I can think of no greater compliment to bestow on an American lawyer.”

(Justice Ginsburg herself usually demurred when the comparison was made, saying that Marshall literally risked his life defending Black clients in the segregated South and that her legal work required no such sacrifice.)

On the court, Justice Ginsburg’s most notable rulings and dissents advanced feminist causes.

In 1996, she authored a groundbreaking decision ordering the Virginia Military Institute to admit women, ending a 157-year tradition of all-male education at the state-funded school.

While Virginia “serves the state’s sons, it makes no provision whatever for her daughters. That is not equal protection,” Justice Ginsburg wrote in United States v. Virginia. The 7-to-1 decision — her friend, Scalia, was the dissenter — was the capstone of the legal battle for gender equality, she said later.

“I regard the VMI case as the culmination of the 1970s endeavor to open doors so that women could aspire and achieve without artificial constraints,” Justice Ginsburg said after the decision.

Among them was a protest of the court’s decision to uphold a federal ban on so-called partial-birth abortions. “The court deprives women of the right to make an autonomous choice, even at the expense of their safety,” Justice Ginsburg wrote. “This way of thinking reflects ancient notions about women’s place in the family and under the Constitution — ideas that have long since been discredited.”

In another, she objected to a ruling that said workers may not sue their employers over unequal pay caused by discrimination alleged to have begun years earlier. That case had been filed by Lilly Ledbetter, the lone female supervisor at a tire plant in Gadsden, Ala., who sued after determining she was paid less than male co-workers.

In an interview with The Post in 2010, Justice Ginsburg said the Ledbetter case struck a personal chord.

“Every woman of my age had a Lilly Ledbetter story,” she said. “And so we knew that the notion that a woman who is in a nontraditional job is going to complain the first time she thinks she is being discriminated against — the one thing she doesn’t want to do is rock the boat, to become known as a complainer.”

She called upon Congress to take action, and once Democrats were in control, it did. Obama signed the law relaxing the deadlines for filing suits.

If the law is often complex, her view of equality was simple, she once said.

“It has always been that girls should have the same opportunity to dream, to aspire and achieve — to do whatever their God-given talents enable them to do — as boys,” Justice Ginsburg said in a 2015 conversation at the American Constitution Society. “There should be no place where there isn’t a welcome mat for women. . . . That’s what it’s all about: Women and men, working together, should help make the society a better place than it is now.”

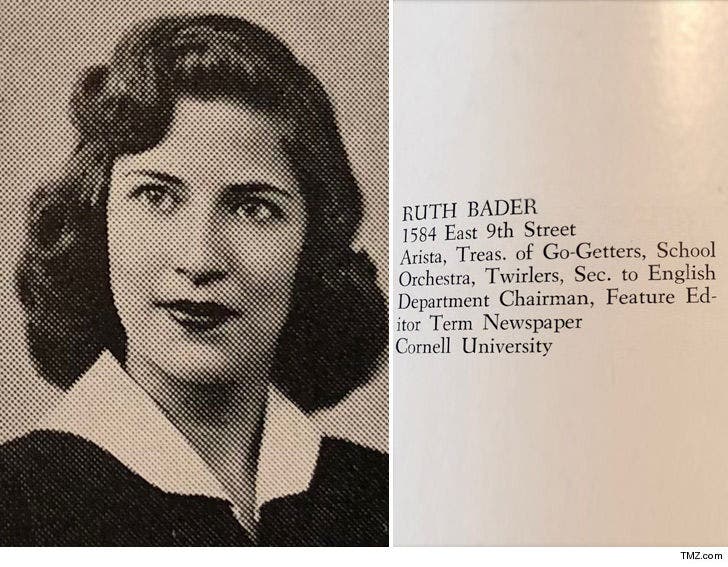

Baton twirler and bookworm

Baton twirler and bookworm

Joan Ruth Bader — her mother suggested using her middle name in kindergarten to avoid confusion with other Joans in the class — was born on March 15, 1933. She was the second daughter of Nathan Bader, a Jewish immigrant from Russia who became a furrier and haberdasher, and the former Celia Amster.

As a schoolgirl, Justice Ginsburg — known to friends as “Kiki” — was smart, popular and competitive, both a bookworm and a baton twirler. But her early life was also shadowed by tragedy. Her older sister, Marilyn, died of meningitis at age 8, leaving Justice Ginsburg to be raised as an only child. She later said she grew up “with the smell of death.”

Raised in Flatbush, then a striving working-class neighborhood of Jewish, Italian and Irish immigrants in Brooklyn, Justice Ginsburg was molded largely by her mother, who had graduated from high school at 15. Her mother never went to college, instead taking a job to help her oldest brother through Cornell University.

Celia Bader was determined that her daughter would have a different path. She stored away money given by her husband for personal expenses to establish a college tuition fund.

But tragedy struck again. By the time Justice Ginsburg was a teenager, her mother was battling cervical cancer. She died in 1950, on the day before Justice Ginsburg graduated near the top of her class from Brooklyn’s James Madison High School.

By the time Celia Bader died, the college fund was $8,000. But her daughter did not need it; she had won enough scholarships to cover her expenses. She ended up giving most of the money to her dad.

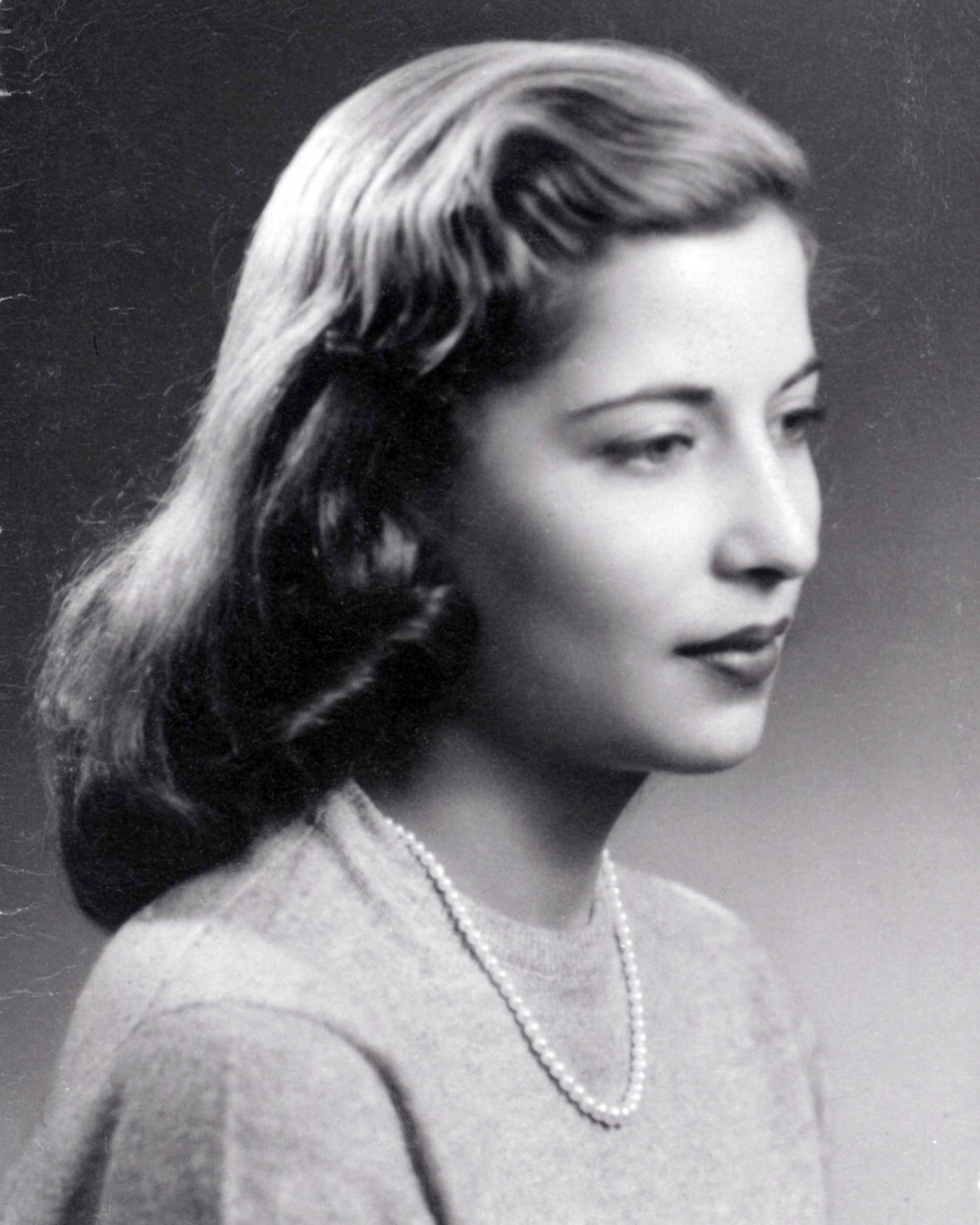

Justice Ginsburg, like her uncle, attended Cornell, where on a blind date she met her future husband, Martin Ginsburg, a confident, fun-loving fraternity member and a standout on the university’s golf team. She later said he was the first boy she ever dated who cared about what was in her head.

After graduation, Martin Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School while Ruth completed her senior year, graduating first in her class in 1954.

Shortly after, they married. He was drafted into the Army, and the couple moved to Lawton, Okla., where Martin was stationed at Fort Sill. While Martin served his two-year hitch, Ruth took a civil service exam and came close to landing a good job at Lawton’s Social Security office.

A problem emerged when she mentioned that she was pregnant. She was told that she would not be allowed to go Baltimore for training, forcing her to settle for a lower-paying job as a typist.

After Martin’s Army discharge in 1956, the couple went to Cambridge, where Ruth also enrolled in Harvard Law, one of nine women in a class of more than 500.

Those were the days of relentless grillings by professors using the Socratic method, a high-pressure situation made even more intense for female students by the prevailing view that they were operating in a realm where they did not belong.

At one point, Dean Erwin Griswold asked the women of the class what it felt like to occupy seats that could have gone to deserving men. (In 1993, on the eve of her Supreme Court confirmation, Griswold told the Harvard Crimson he long favored admitting women but that he had been overruled by the university’s governing board. He added that in asking women such a provocative question, he was playing devil’s advocate. “I think she completely misunderstood it and should have known better,” he said.)

Further complicating matters for Justice Ginsburg as a Harvard student was the responsibility of being a new mother after the birth of her daughter, Jane. (Jane eventually attended Harvard Law as well, one year behind future Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.)

Through it all, Justice Ginsburg was an academic star at Harvard. She earned top grades and a spot on the law review. But crisis soon invaded her life once again when her husband was diagnosed with testicular cancer. The prognosis was dire. “At the time, there were no known survivors,” Justice Ginsburg said.

Doctors treated the ailment with both radiation and surgery. Justice Ginsburg collected carbon copies of class notes from Martin’s classmates, and she typed his papers as he dictated before turning to her own studies. Martin eventually recovered and after graduation snagged a job at a New York firm.

In 1958, Ruth transferred from Harvard to Columbia Law School to complete her legal training. There, she continued to thrive, again making the law review and tying for first in her class at graduation in 1959.

Once she started looking for work, she could not find a job at New York’s top firms.

“I struck out on three grounds — I was Jewish, a woman and a mother,” Justice Ginsburg reflected later. “The first raised one eyebrow; the second, two; the third made me indubitably inadmissible.”

Nor could she land an interview for a clerkship with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, despite a recommendation from a dean of Harvard Law School. Frankfurter made it clear that he simply wasn’t ready to hire a woman.

Eventually, she landed a position as a clerk for a federal district court judge, after a Columbia law professor lined up a man as a replacement in the event Justice Ginsburg faltered.

After her clerkship, Justice Ginsburg signed on for a summer fellowship to study the legal system in Sweden. The six weeks in Stockholm proved to be an awakening, as she was thrust into the midst of that country’s burgeoning debate about gender roles in raising families.

The question was easily settled in Justice Ginsburg’s personal life, even as it roiled around her. She and Martin shared child rearing and household duties. She liked to tell the story of her response to receiving repeated calls from school administrators about discipline problems with her son, James.

On one “particularly weary” day, she told the school, “This child has two parents. I suggest you alternate calls, and it’s his father’s turn.”

During her tenure on the court, Martin, a tax expert and later a Georgetown University Law School instructor who died in 2010, often baked cakes for justices’ birthday celebrations. He also was a reliable contributor to the spouse lunches and dinners held by the justices at the court.

Martin Ginsburg once proposed this response to public requests for Justice Ginsburg’s “favorite recipe”: “The Justice was expelled from the kitchen nearly three decades ago by her food-loving children. She no longer cooks and the one recipe from her youth, tuna fish casserole, is nobody’s favorite.”

A 'sparrow,' not a robin

In 1963, Justice Ginsburg became the second woman to join the faculty at New Jersey’s Rutgers Law School. There, her feminist awakening continued, even if she probably would not have described it that way.

When Justice Ginsburg learned that her salary was lower than that of male colleagues, she joined an equal pay campaign with other female teachers, which resulted in raises for the women.

While teaching at Rutgers, she also began taking on cases on behalf of the New Jersey branch of the ACLU. She battled successfully for maternity leave rights for teachers in New Jersey, who previously faced the threat of dismissal when they became pregnant.

In 1972, Justice Ginsburg became the first woman hired with tenure at Columbia Law School. Around that time, she also became the first director of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project.

At the ACLU, Justice Ginsburg led a team of lawyers that brought six cases before the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1979. They won five, victories that eventually altered the nation’s legal terrain by establishing that the constitutional guarantee of equal protection applied not only to racial minorities but to women as well.

In many ways, she was an unlikely revolutionary. Friends called her shy, and detractors and even her family said she could be humorless. But at times, she could be whimsical and was known to have a wry wit. Opera was her passion, and she said she would have been a diva instead of a justice if she’d had the voice of a robin instead “of a sparrow.”

In 1994, she and Scalia appeared in 18th-century costumes as extras in the Washington National Opera’s production of Richard Strauss’s “Ariadne auf Naxos.” Later, composer-librettist Derrick Wang took words from their opinions and put them to music in an opera called “Scalia/Ginsburg.” She often was asked why that order, instead of alphabetical?

Seniority reigns at the Supreme Court, Ginsburg answered, and Scalia got there first.

Roe and Clinton

Her early victories at the Supreme Court prompted President Jimmy Carter to appoint her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in 1980.

On an appeals court that often divided along ideological lines, Justice Ginsburg frequently straddled the middle. She dissented from the majority’s refusal to hear the case of an Air Force officer who wanted to wear a yarmulke while on duty, saying the prohibition reflected “callous indifference” to his religious faith.

On the other hand, Justice Ginsburg voted to dismiss a case brought by a gay sailor discharged from the Navy, and she voted against a minority set-aside program in O’Donnell Construction Co. v. District of Columbia. She developed enduring friendships with conservative jurists Scalia and Robert H. Bork while all three served on the appeals court.

A strong supporter of abortion rights, Justice Ginsburg nonetheless alienated some of her erstwhile allies with a 1984 speech at the University of North Carolina, where she criticized the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Roe v. Wade that guaranteed abortion rights.

The court’s 1973 ruling was too sweeping, she said, contributing to the divisive rancor that has accompanied the abortion issue ever since. She suggested that the court and the cause of abortion rights would have been better served had the court simply overturned the Texas law outlawing almost all abortions, which was at issue in the case.

She clarified her position in a 1993 lecture in which she argued that the justices should have grounded the right to abortion not in the concepts of “personal liberty” and “privacy” that spring from the 14th Amendment, but in the amendment’s equal protection clause.

Her novel views on Roe created a significant hurdle for her ascension to the high court. After White announced his resignation in 1993, Justice Ginsburg, then 60, was among a large group of potential nominees placed before Clinton.

Justice Ginsburg faced opposition from a new generation of women’s activists who, citing her abortion rights speeches and record as a moderate on the appeals court, argued that her views were too narrow and that time had passed her by.

Justice Ginsburg also had her supporters, including her husband, who helped organize an effort that resulted in a torrent of letters and telephone calls to the White House that prompted Clinton to give her a second look. Clinton was also spurred on by Senate conservatives who pointed to Justice Ginsburg as a moderate that they could support, which appealed to Clinton’s New Democrat leanings. Clinton announced her nomination on June 14, 1993. She was confirmed just over two months later by a 96-to-3 vote.

After the president announced her nomination, the normally reserved Ginsburg took time to thank a list of people and causes, including the civil rights and women’s movements, her husband and two children, her mother-in-law and first lady Hillary Clinton. Then, she offered one final tribute.

“It is to my mother, Celia Amster Bader, the bravest and strongest person I have known, who was taken from me much too soon,” Justice Ginsburg said. “I pray that I may be all that she would have been had she lived in an age when women could aspire and achieve, and daughters are cherished as much as sons.”

A prolific dissent writer

Justice Ginsburg’s lot was to serve on a court with a majority more conservative than she was. As a result, she became much more known for her dissents than her majority opinions. More-moderate justices such as Sandra Day O’Connor, whom Justice Ginsburg greatly admired, and Kennedy often were the ones who wrote when the court was ideologically divided.

Justice Ginsburg wrote a powerful dissent in one of the pivotal cases in her time on the court — Bush v. Gore — which resulted in George W. Bush’s win in the 2000 election. The majority criticized and then shut down a recount by Florida officials, which she would have allowed to continue.

“Ideally, perfection would be the appropriate standard for judging the recount,” she wrote. “But we live in an imperfect world, one in which thousands of votes have not been counted. I cannot agree that the recount adopted by the Florida court, flawed as it may be, would yield a result any less fair or precise than the certification that preceded that recount.”

When Justice John Paul Stevens retired in 2010, Justice Ginsburg became the senior justice among the court’s liberals: her fellow Clinton nominee Stephen G. Breyer and Obama’s choices for the court, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Under Justice Ginsburg’s direction, the liberals often answered major decisions with which they disagreed with one unified dissent. And they swallowed any differences they had with Kennedy to join him in a string of liberal victories at the court on same-sex marriage, affirmative action and abortion. (Justice Ginsburg later became the first justice to perform a same-sex marriage ceremony.)

When the court in 2016 struck down Texas restrictions on doctors and abortion clinics, Kennedy assigned the majority opinion to Breyer. But Justice Ginsburg issued a rare concurrence to make the point that abortion rights remained — for now — firmly established.

As long as Roe remains good law, Justice Ginsburg wrote, laws that “do little or nothing for health, but rather strew impediments to abortion, cannot survive judicial inspection.”

Justice Ginsburg did most of her work in dissents. She said she most lamented the court’s decisions in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), which opened the way for greater corporate and union spending in elections, and Shelby County v. Holder (2013), in which the court threw out a key provision of the civil rights-era Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In a famous passage, she faulted Roberts’s logic that restrictions on states with past desegregation needed to be justified anew.

“Throwing out pre-clearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet,” she wrote.

Justice Ginsburg sometimes drew attention for more than her legal opinions. Tiny and frail-looking, despite the fact that she worked out with a trainer and boasted of doing push-ups, photos of Justice Ginsburg falling asleep at the State of the Union address became the subject of news reports. She explained that it wasn’t fatigue; in fact, she was known as something of a night owl, working late. Instead, she said, Kennedy had brought a good bottle of wine to the dinner that the justices traditionally hold before crossing the street to the Capitol.

Justice Ginsburg was also criticized for speaking too frankly in interviews and speeches, especially about abortion rights and same-sex marriage.

She drew criticism for surprisingly critical remarks about businessman Donald Trump, saying she feared for the court and the country if he were elected president. After several days of controversy, she issued a statement saying it was wrong of her to have commented about politics, but not apologizing for her views.

During her court tenure, Justice Ginsburg had several bouts with cancer, although she never missed a day of the court’s public schedule.

She had colon cancer surgery in 1999, which was accompanied by precautionary chemotherapy and radiation treatment, but she never missed a day of oral arguments. And in February 2009, she underwent surgery for early-stage pancreatic cancer but managed to return to the bench when the court returned from recess less than three weeks later.

Instead, cancer took her husband first. Again, she was on the bench the next day.

It was the final day of the court’s term, and she had an opinion to deliver. She thought of having another justice read the summary for her, but her children insisted she go herself, saying it was what their father would have wanted.

Justice Ginsburg’s survivors include two children, Jane C. Ginsburg and James S. Ginsburg; four grandchildren; two step-grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.