|

| A cricket game in New Zealand. |

NICHOLAS KRISTOF, N.Y. TIMES

We in the United States grow up celebrating ourselves as the world’s most powerful nation, the world’s richest nation, the world’s freest and most blessed nation.

Sure, technically Norwegians may be wealthier per capita, and the Japanese may live longer, but the world watches the N.B.A., melts at Katy Perry, uses iPhones to post on Facebook, trembles at our aircraft carriers, and blames the C.I.A. for everything. We’re No. 1!

In some ways we indisputably are, but a major new ranking of livability in 132 countries puts the United States in a sobering 16th place. We underperform because our economic and military strengths don’t translate into well-being for the average citizen.

In

the Social Progress Index, the United States excels in access to advanced education but ranks 70th in health, 69th in ecosystem sustainability, 39th in basic education, 34th in access to water and sanitation and 31st in personal safety. Even in access to cellphones and the Internet, the United States ranks a disappointing 23rd, partly because

one American in five lacks Internet access.

“It’s astonishing that for a country that has Silicon Valley, lack of access to information is a red flag,” notes Michael Green, executive director of

the Social Progress Imperative, which oversees the index. The United States has done better at investing in drones than in children, and cuts in social services could fray the social fabric further.

This Social Progress Index ranks New Zealand No. 1, followed by Switzerland, Iceland and the Netherlands. All are somewhat poorer than America per capita, yet they appear to do a better job of meeting the needs of their people.

The Social Progress Index is a brainchild of Michael E. Porter, the eminent Harvard business professor who earlier helped develop the Global Competitiveness Report. Porter is a Republican whose work, until now, has focused on economic metrics.

“This is kind of a journey for me,” Porter told me. He said that he became increasingly aware that social factors support economic growth: tax policy and regulations affect economic prospects, but so do schooling, health and a society’s inclusiveness.

So Porter and a team of experts spent two years developing this index, based on a vast amount of data reflecting suicide, property rights, school attendance, attitudes toward immigrants and minorities, opportunity for women, religious freedom, nutrition, electrification and much more.

Many who back

proposed Republican cuts in Medicaid, food stamps and public services believe that such trims would boost America’s competitiveness. Looking at this report, it seems that the opposite is true.

Ireland, from which so many people fled in the 19th century to find opportunity in the United States, now ranks 15th. That’s a notch ahead of the United States, and Ireland is also ahead of America in the category of “opportunity.”

Canada came in seventh, the best among the nations in the G-7. Germany is 12th, Britain 13th and Japan 14th.

The bottom spot on the ranking was filled by Chad. Just above it were Central African Republic, Burundi, Guinea, Sudan and Angola.

...some countries punch well above their weight. Costa Rica performs better than much richer countries, and so do the Philippines, Estonia and Jamaica. In Africa, Malawi, Ghana and Liberia shine. Bangladesh (no. 99) ranks ahead of wealthier India (no. 102). Likewise, Ukraine (no. 62) outperforms Russia (no. 80).

China does poorly, ranking 90th, behind its poorer neighbor Mongolia (no. 89). China performs well in basic education but lags in areas such as personal rights and access to information.

All this goes to what kind of a nation we want to be, and whether we put too much faith in G.D.P. as a metric.

Over all,

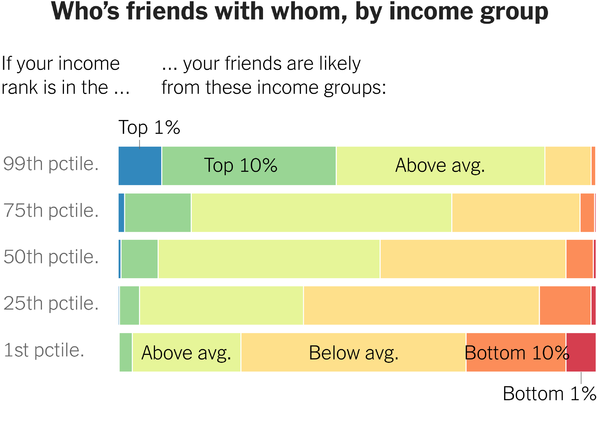

the United States’ economy outperformed France’s between 1975 and 2006. But 99 percent of the French population actually enjoyed more gains in that period than 99 percent of the American population. Exclude the top 1 percent, and the average French citizen did better than the average American. This lack of shared prosperity and opportunity has stunted our social progress.

There are no quick fixes, but basic education and health care are obvious places to begin, especially in the first few years of life, when returns are the highest.

The arguments for boosting opportunity or social services usually revolve around social justice and fairness. The Social Progress Index offers a reminder that what’s at stake is also the health of our society — and our competitiveness around the globe.