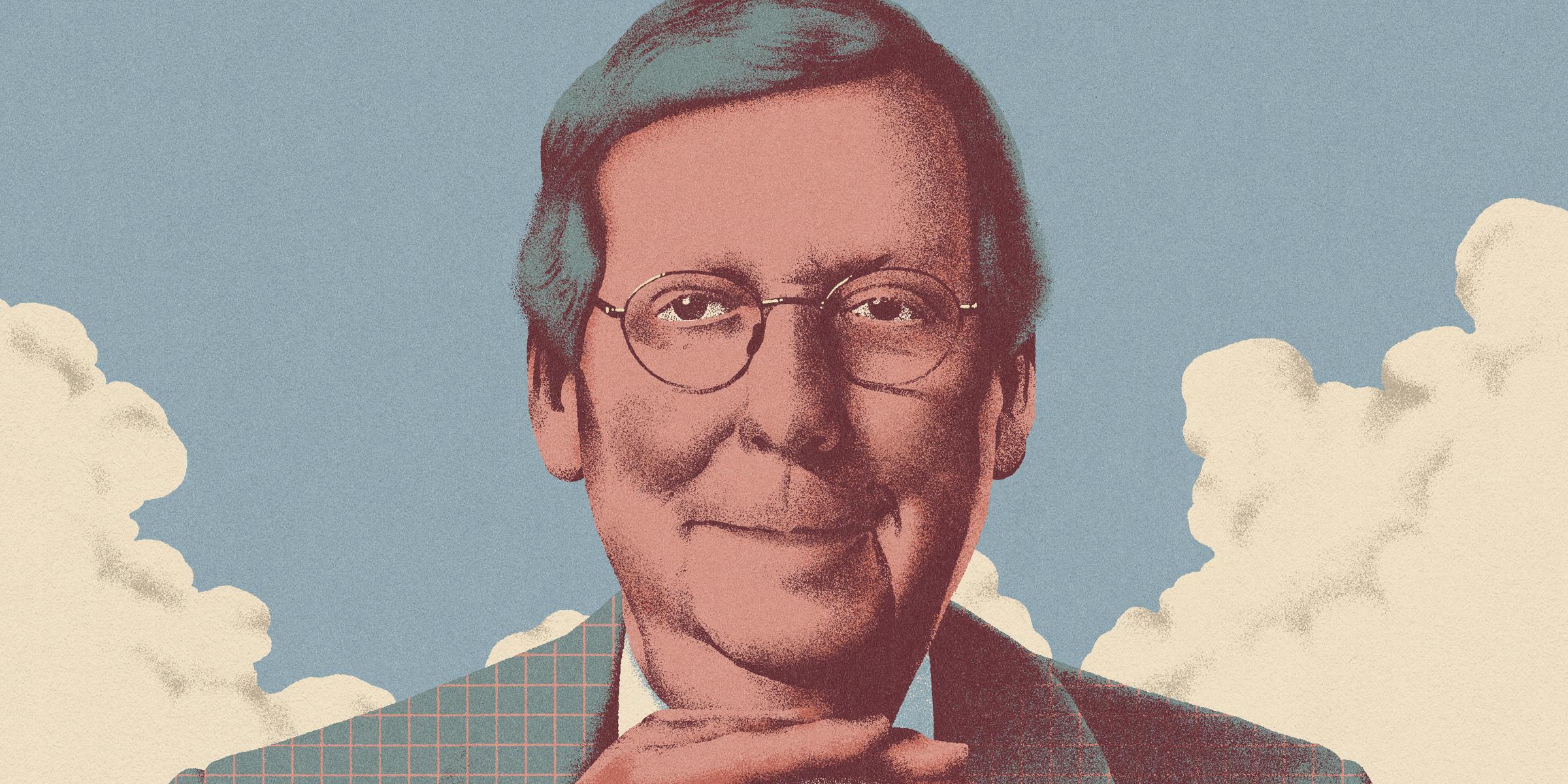

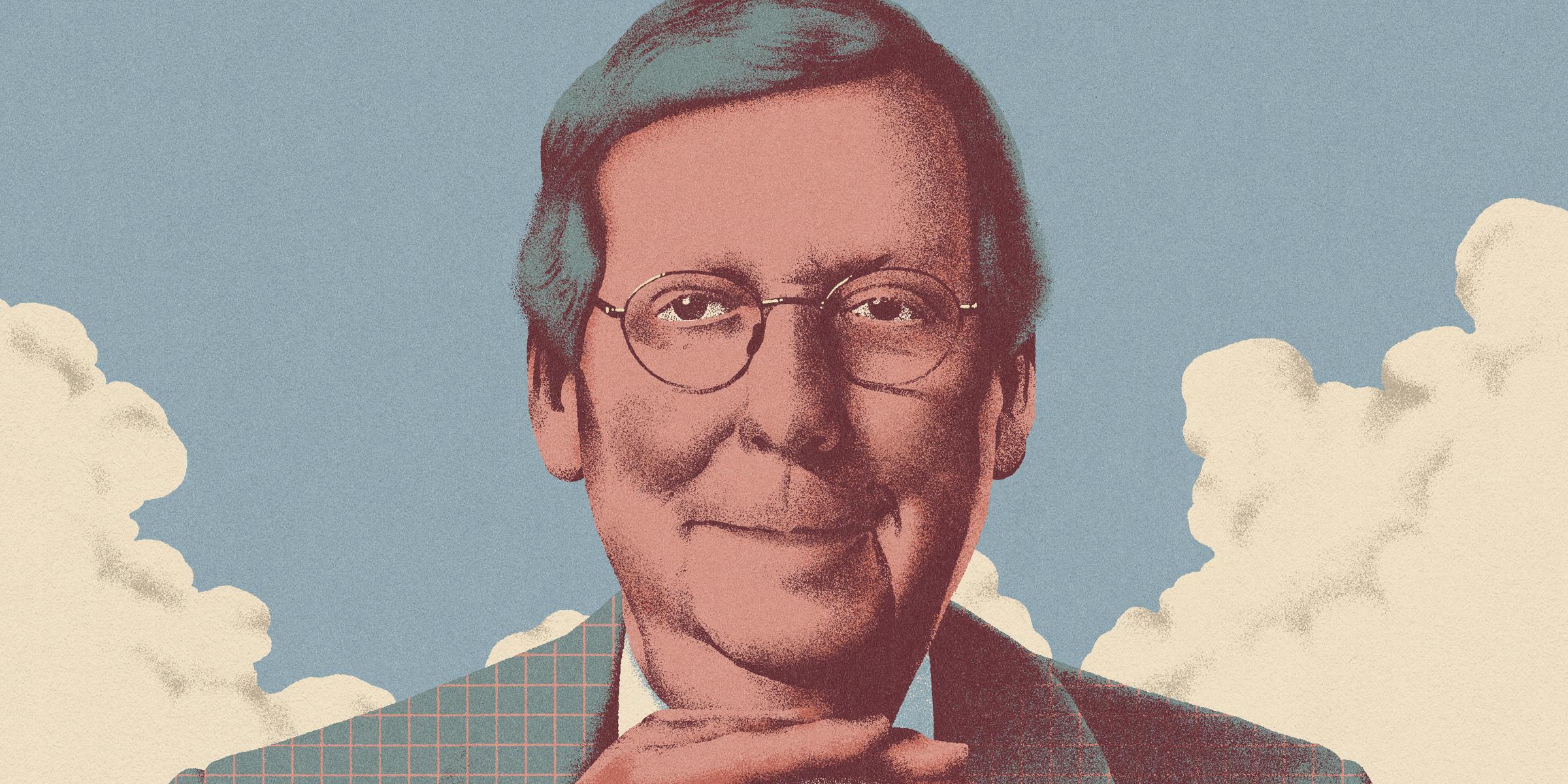

On Thursday, March 12th, Mitch McConnell, the Senate Majority Leader, could have insisted that he and his colleagues work through the weekend to hammer out an emergency aid package addressing the coronavirus pandemic. Instead, he recessed the Senate for a long weekend, and returned home to Louisville, Kentucky. McConnell, a seventy-eight-year-old Republican who is about to complete his sixth term as a senator, planned to attend a celebration for a protégé, Justin Walker, a federal judge who was once his Senate intern. McConnell has helped install nearly two hundred conservatives as judges; stocking the judiciary has been his legacy project.

Soon after he left the Capitol, Democrats in the House of Representatives settled on a preliminary rescue package, working out the details with the Treasury Secretary, Steven Mnuchin. The Senate was urgently needed for the next steps in the process. McConnell, though, was onstage in a Louisville auditorium, joking that his opponents “occasionally compare me to Darth Vader.”

The gathering had the feel of a reunion. Don McGahn, Donald Trump’s former White House counsel, whom McConnell has referred to as his “buddy and co-collaborator” in confirming conservative judges, flew down for the occasion. So did Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, whose Senate confirmation McConnell had fought fiercely to secure. Walker, the event’s honoree, had clerked for Kavanaugh, and became one of his lead defenders after Kavanaugh was accused of sexual assault. McConnell is now championing Walker for an opening on the powerful D.C. Court of Appeals, even though Walker has received a “not qualified” rating from the American Bar Association, in part because, at the age of thirty-eight, he has never tried a case.

Another former Senate aide of McConnell’s, a U.S. district judge for the Eastern District of Kentucky, Gregory Van Tatenhove, also attended the Louisville event. His wife, Christine, is a former undergraduate scholar at the McConnell Center—an academic program at the University of Louisville which, among other things, hosts an exhibit honoring the Senator’s career. Recently, she donated a quarter of a million dollars to the center.

McConnell, a voracious reader of history, has been cultivating his place in it for many years. But, in leaving Washington for the long weekend, he had misjudged the moment. The hashtag #WheresMitch? was trending on Twitter. President Trump had declared a national emergency; the stock market had ended one of its worst weeks since the Great Recession. Nearly two thousand cases of covid-19 had already been confirmed in America.

Eleven days later, the Senate still had not come up with a bill. The Times ran a scorching editorial titled “The Coronavirus Bailout Stalled. And It’s Mitch McConnell’s Fault.” The Majority Leader had tried to jam through a bailout package that heavily favored big business. But by then five Republicans were absent in self-quarantine, and the Democrats forced McConnell to accept a $2.1-trillion compromise bill that reduced corporate giveaways and expanded aid to health-care providers and to hard-hit workers.

McConnell, who is known as one of the wiliest politicians in Washington, soon reframed the narrative as a personal success story. In Kentucky, where he is running for reëlection, he launched a campaign ad about the bill’s passage, boasting, “One leader brought our divided country together.” At the same time, he attacked the Democrats, telling a radio host that the impeachment of Trump had “diverted the attention of the government” when the epidemic was in its early stages. In fact, several senators—including Tom Cotton, a Republican from Arkansas, and Chris Murphy, a Democrat from Connecticut—had raised alarms about the virus nearly two months before the Administration acted, whereas Trump had told reporters around the same time that he was “not concerned at all.” And on February 27th, some three weeks after the impeachment trial ended, McConnell had defended the Administration’s response, accusing Democrats of “performative outrage” when they demanded more emergency funding.

Many have regarded McConnell’s support for Trump as a stroke of cynical political genius. McConnell has seemed to be both protecting his caucus and covering his flank in Kentucky—a deep-red state where, perhaps not coincidentally, Trump is far more popular than he is. When the pandemic took hold, the President’s standing initially rose in national polls, and McConnell and Trump will surely both take credit for the aid package in the coming months. Yet, as covid-19 decimates the economy and kills Americans across the nation, McConnell’s alliance with Trump is looking riskier. Indeed, some critics argue that McConnell bears a singular responsibility for the country’s predicament. They say that he knew from the start that Trump was unequipped to lead in a crisis, but, because the President was beloved by the Republican base, McConnell protected him. He even went so far as to prohibit witnesses at the impeachment trial, thus guaranteeing that the President would remain in office. David Hawpe, the former editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal, said of McConnell, “There are a lot of people disappointed in him. He could have mobilized the Senate. But the Republican Party changed underneath him, and he wanted to remain in power.”

Stuart Stevens, a longtime Republican political consultant, agrees that McConnell’s party deserves a considerable share of the blame for America’s covid-19 disaster. In a forthcoming book, “It Was All a Lie,” Stevens writes that, in accommodating Trump and his base, McConnell and other Republicans went along as Party leaders dismantled the country’s safety net and ignored experts of all kinds, including scientists. “Mitch is kidding himself if he thinks he’ll be remembered for anything other than Trump,” he said. “He will be remembered as the Trump facilitator.”

The President is vindictive toward Republicans who challenge him, as Mitt Romney can attest. Yet Stevens believes that the conservatives who have acceded to Trump will pay a more lasting price. “Trump was the moral test, and the Republican Party failed,” Stevens said. “It’s an utter disaster for the long-term fate of the Party. The Party has become an obsession with power without purpose.”

Bill Kristol, a formerly stalwart conservative who has become a leading Trump critic, describes McConnell as “a pretty conventional Republican who just decided to go along and get what he could out of Trump.” Under McConnell’s leadership, the Senate, far from providing a check on the executive branch, has acted as an accelerant. “Demagogues like Trump, if they can get elected, can’t really govern unless they have people like McConnell,” Kristol said. McConnell has stayed largely silent about the President’s lies and inflammatory public remarks, and has propped up the Administration with legislative and judicial victories. McConnell has also brought along the Party’s financial backers. “There’s been too much focus on the base, and not enough on business leaders, big donors, and the Wall Street Journal editorial page,” Kristol said, adding, “The Trump base would be there anyway, but the élites might have rebelled if not for McConnell. He could have fundamentally disrupted Trump’s control, but instead McConnell has kept the trains running.”

McConnell and the President are not a natural pair. A former Trump Administration official, who has also worked in the Senate, observed, “It would be hard to find two people less alike in temperament in the political arena. With Trump, there’s rarely an unspoken thought. McConnell is the opposite—he’s constantly thinking but says as little as possible.” The former Administration official went on, “Trump is about winning the day, or even the hour. McConnell plays the long game. He’s sensitive to the political realities. His North Star is continuing as Majority Leader—it’s really the only thing for him. He’s patient, sly, and will obfuscate to make less apparent the ways he’s moving toward a goal.” The two men also have different political orientations: “Trump is a populist—he’s not just anti-élitist, he’s anti-institutionalist.” As for McConnell, “no one with a straight face would ever call him a populist—Trump came to drain the swamp, and now he’s working with the biggest swamp creature of them all.”

When Trump ran for President, he frequently derided “the corrupt political establishment,” saying that Wall Street titans were “getting away with murder” by paying no taxes. In a furious campaign ad, images of the New York Stock Exchange and the C.E.O. of Goldman Sachs flashed onscreen as he promised an end to the élites who had “bled our country dry.” In interviews, he denounced his opponents for begging wealthy donors for campaign contributions, arguing that, if “somebody gives them money,” then “just psychologically, when they go to that person they’re going to do it—they owe him.”

|

| Never Trump stategist Rick Wilson |

McConnell, by contrast, is the master of the Washington money machine. Nobody has done more than he has to engineer the current campaign-finance system, in which billionaires and corporations have virtually no spending limits, and self-dealing and influence-peddling are commonplace. Rick Wilson, a Never Trumper Republican [above] and a former political consultant who once worked on races with McConnell’s team, said, “McConnell’s an astounding behind-the-scenes operator who’s got control of the most successful fund-raising operation in history.” Former McConnell staffers run an array of ostensibly independent spending groups, many of which take tens of millions of dollars from undisclosed donors. Wilson considers McConnell, who has been Majority Leader since 2015, a realist who does whatever is necessary to preserve both his own political survival and the Republicans’ edge in the Senate, which now stands at 53–47. “He feels no shame about it,” he said. “McConnell has been the most powerful force normalizing Trump in Washington.”

Al Cross, a columnist and a journalism professor at the University of Kentucky, who is considered the dean of the state’s political press corps, believes that McConnell’s partnership with Trump “is the most important political relationship in the country.” He had hoped that McConnell would push back against Trump. After all, past Republicans have crossed party lines to defend democracy—from censuring Joe McCarthy to forcing the resignation of President Richard Nixon. “But Trump and McConnell have come to understand each other,” Cross said. “The President needs him to govern. McConnell knows that if their relationship fell apart it would be a disaster for the Republican majority in the Senate. They’re very different in many ways, but fundamentally they’re about the same thing—winning.”

In a forthcoming book, “Let Them Eat Tweets,” the political scientists Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson challenge the notion that the Republican Party is riven between global corporate élites and downscale white social conservatives. Rather, they argue, an “expedient pact” lies at the heart of today’s Party—and McConnell and Trump embody it. Polls show that there is little voter support for wealthy donors’ agenda of tax cuts for themselves at the expense of social-safety-net cuts for others. The Republicans’ 2017 tax bill was a case in point: it rewarded the Party’s biggest donors by bestowing more than eighty per cent of its largesse on the wealthiest one per cent, by cutting corporate tax rates, and by preserving the carried-interest loophole, which is exploited by private-equity firms and hedge funds. The legislation was unpopular with Democratic and Republican voters alike. In order to win elections, Hacker and Pierson explain, the Republican Party has had to form a coalition between corporatists and white cultural conservatives who are galvanized by Trump’s anti-élitist and racist rhetoric. The authors call this hybrid strategy Plutocratic Populism. Hacker told me that the relationship between McConnell and Trump offers “a clear illustration of how the Party has evolved,” adding, “They may detest each other, but they need each other.”

Although the two men almost always support each other in public, several members of McConnell’s innermost circle told me that in private things are quite different. They say that behind Trump’s back McConnell has called the President “nuts,” and made clear that he considers himself smarter than Trump, and that he “can’t stand him.” (A spokesman for McConnell, who declined to be interviewed, denies this.) According to one such acquaintance, McConnell said that Trump resembles a politician he loathes: Roy Moore, the demagogic former chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, whose 2017 campaign for an open U.S. Senate seat was upended by allegations that he’d preyed on teen-age girls. (Moore denies them.) “They’re so much alike,” McConnell told the acquaintance.

McConnell’s political fealty to Trump has cost him the respect of some of the people who have known him the longest. David Jones, the late co-founder of the health-care giant Humana, backed all McConnell’s Senate campaigns, starting in 1984; Jones and his company’s foundation collectively gave $4.6 million to the McConnell Center. When Jones died, last September, McConnell described him as, “without exaggeration, the single most influential friend and mentor I’ve had in my entire career.” But, three days before Jones’s death, Jones and his two sons, David, Jr., and Matthew, sent the second of two scorching letters to McConnell, both of which were shared with me. They called on him not to be “a bystander” and to use his “constitutional authority to protect the nation from President Trump’s incoherent and incomprehensible international actions.” They argued that “the powers of the Senate to constrain an errant President are prodigious, and it is your job to put them to use.” McConnell had assured them, in response to their first letter, that Trump had “one of the finest national-security teams with whom I have had the honor of working.” But in the second letter the Joneses replied that half of that team had since gone, leaving the Department of Defense “leaderless for months,” and the office of the director of National Intelligence with only an “ ‘acting’ caretaker.” The Joneses noted that they had all served the country: the father in the Navy, Matthew in the Marine Corps, and David, Jr., in the State Department, as a lawyer. Imploring McConnell “to lead,” they questioned the value of “having chosen the judges for a republic while allowing its constitutional structures to fail and its strength and security to crumble.”

John David Dyche, a lawyer in Louisville and until recently a conservative columnist, enjoyed unmatched access to McConnell and his papers, and published an admiring biography of him in 2009. In March, though, Dyche posted a Twitter thread that caused a lot of talk in the state’s political circles. He wrote that McConnell “of course realizes that Trump is a hideous human being & utterly unfit to be president,” and that, in standing by Trump anyway, he has shown that he has “no ideology except his own political power.” Dyche declined to comment for this article, but, after the coronavirus shut down most of America, he announced that he was contributing to McConnell’s opponent, Amy McGrath, and tweeted, “Those who stick with the hideous, incompetent demagogue endanger the country & will be remembered in history as shameful cowards.”

McConnell also appears to have lost the political support of his three daughters. The youngest, Porter, is a progressive activist who is the campaign director for Take On Wall Street, a coalition of labor unions and nonprofit groups which advocates against the “predatory economic power” of “banks and billionaires.” One of its targets has been Stephen Schwarzman, the chairman and C.E.O. of the Blackstone Group, who, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, has, since 2016, donated nearly thirty million dollars to campaigns and super pacs aligned with McConnell. Last year, Take On Wall Street condemned Blackstone’s “detrimental behavior” and argued that the company’s campaign donations “cast a pall on candidates’ ethics.”

Porter McConnell has also publicly criticized the Senate’s confirmation of Justice Kavanaugh, which her father considers one of his greatest achievements. On Twitter, she accused Kavanaugh’s supporters of misogyny, and retweeted a post from StandWithBlaseyFord, a Web site supporting Christine Blasey Ford, one of Kavanaugh’s accusers. The husband of McConnell’s middle daughter, Claire, has also criticized Kavanaugh online, and McConnell’s eldest daughter, Eleanor, is a registered Democrat.

All three daughters declined to comment, as did their mother, Sherrill Redmon, whom McConnell divorced in 1980. After the marriage ended, Redmon, who holds a Ph.D. in philosophy, left Kentucky and took over a women’s-history archive at Smith College, in Massachusetts, where she collaborated with Gloria Steinem on the Voices of Feminism Oral History Project. In an e-mail, Steinem told me that Redmon rarely spoke about McConnell, and noted, “Despite Sherrill’s devotion to recording all of women’s lives, she didn’t talk about the earlier part of her own.” Steinem’s understanding was that McConnell’s political views had once been different. “I can only imagine how painful it must be to marry and have children with a democratic Jekyll and see him turn into a corrupt and authoritarian Hyde,” she wrote. (Redmon is evidently working on a tell-all memoir.)

Steinem’s comment echoed a common belief about McConnell: that he began his career as an idealistic, liberal Republican in the mold of Nelson Rockefeller. Certainly, McConnell’s current positions on several key issues, including campaign spending and organized labor, are far more conservative than they once were. But when I asked John Yarmuth, the Democratic congressman from Louisville, who has known McConnell for fifty years, if McConnell had once been idealistic, he said, “Nah. I never saw any evidence of that. He was just driven to be powerful.”

Yarmuth, who began as a Republican and worked in a statewide campaign alongside McConnell in 1968, said that McConnell had readily adapted to the Republican Party’s rightward march: “He never had any core principles. He just wants to be something. He doesn’t want to do anything.”

For months, I searched for the larger principles or sense of purpose that animates McConnell. I travelled twice to Kentucky, observed him at a Trump rally in Lexington, and watched him preside over the impeachment trial in Washington. I interviewed dozens of people, some of whom love him and some of whom despise him. I read his autobiography, his speeches, and what others have written about him. Finally, someone who knows him very well told me, “Give up. You can look and look for something more in him, but it isn’t there. I wish I could tell you that there is some secret thing that he really believes in, but he doesn’t.”

The notion that McConnell started out as an idealist is a staple of most versions of his life story, including his own autobiography, “The Long Game,” published in 2016. He describes his awe, as a young congressional intern, at seeing crowds gather on the Washington Mall for Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in 1963. McConnell, who was on summer break from the University of Louisville, writes that he recognized he “was witnessing a pivotal moment in history.”

McConnell was born in Alabama in 1942, and grew up in the segregated Deep South. He spent much of his childhood in Georgia before moving with his family to Louisville, Kentucky, just before his high-school years. His mother, the daughter of Alabama subsistence farmers, was a secretary in Birmingham when she met McConnell’s father, a mid-level corporate manager who had grown up in a more prosperous family but had dropped out of college. McConnell, in his autobiography, describes his mother’s wedding dowry as little more than “an apple corer and a can opener.” But his parents, he writes, gave him a comfortable middle-class childhood and “instilled me with a deep-seated belief in equal and civil rights, which, given their own upbringing in the Deep South, was quite extraordinary.” He quotes a moving letter from his father celebrating the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and writes that he, too, supported the legislation. That year, McConnell even voted for Lyndon Johnson for President.

McConnell’s book does not mention that his father, who worked in the human-resources department at DuPont, was deposed by lawyers for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund in a historic racial-discrimination case. Kerry Scanlon, one of the lawyers, told me, “The leadership at that plant seemed to define racism. There was a plantation system in which the black employees did the hardest jobs, like working in front of these open fires where they got burned—and they got the worst pay. There was a systemic pattern of racism.” After years of litigation, the company settled the case, for fourteen million dollars.

McConnell writes that the formative experience of his early life was contracting polio at the age of two, ten years before Jonas Salk developed his vaccine. McConnell’s father was away, having joined the military after the start of the Second World War, and so for the next two years his mother, largely alone, confined him to bed except for a painful daily regimen of exercises. His first memory is of his mother’s purchase of a pair of saddle shoes that allowed him to look like other kids once the doctors finally allowed him to walk. He emerged unimpaired, other than having a weak left leg. He credits the experience, and his mother’s determination, with giving him the focus and drive that have propelled him throughout his career. Beating polio, he writes, was the first in a lifetime pursuit of hard-fought “wins.” In recent weeks, as McConnell has contended with the coronavirus challenge, he has said that it brings back “this eerie feeling” of “fear that every mother had” during a polio epidemic.

An only child, McConnell remained close to his mother, who shared his flinty personality. He also remained devoted to the idea that grit and preparation could beat even the longest odds. He keeps on his office wall a framed copy of a quotation often attributed to Calvin Coolidge, which begins, “Nothing in the world can take the place of Persistence.” (Some people who knew of this found it ironic when, in 2017, in the Senate, he criticized Elizabeth Warren for refusing to yield the floor, complaining, “She persisted.”)

In his book, McConnell recounts a day when his father ordered him to cross the street and beat up an older boy who had been pushing him around. McConnell protested that the boy was bigger, but his father said, “It’s time you showed him who’s boss.” Fearing his father more than the bully, McConnell went over and sucker-punched his neighbor. McConnell writes that the lesson taught him the importance of “standing up for myself, knowing there’s a point beyond which I can’t be pushed, and being tough.” He admits that he’s been criticized for his toughness, but adds that “it’s almost always worked.”

McConnell’s first ambition was to be a baseball player. He was a good Little League pitcher, but by middle school his physical limitations ended his hopes. According to people who know him, his box-score approach to politics—“Our team against their team,” as one put it—is merely a substitute for his competitive approach to sports.

When McConnell tells the story of his first campaign—for student-council president—what leaps out is that he seemed far more interested in winning the title than in doing anything with it. As an underclassman, he was an introvert who sat by himself in the back of the auditorium at assemblies, and he was dazzled by the student-council president, who “had the envy of everyone.” When he confided this to his mother, she encouraged him to run for the position. He told her, “I don’t have even one friend.” But, McConnell writes, he went ahead, realizing that he could hustle endorsements from popular cheerleaders and athletes by giving them the “one thing teenagers most desire. Flattery.” He won. He writes that, upon having his first taste of the respect that comes with holding elected office, “I was hooked.”

McConnell was the kind of political nerd who, as a kid, watched both parties’ Conventions gavel to gavel, and he soon set his sights on a goal: becoming a U.S. senator. He wrote his college thesis on Kentucky’s famed nineteenth-century senator Henry Clay, who was known as the Great Compromiser. The Senate seemed like the ideal place for McConnell: he lacked charisma but had single-minded ambition, as well as a gift for savvy, farsighted planning. He also had a flair for cultivating powerful backers, and for what he has called “calculated résumé-building activities.” After college, he got an internship with the Kentucky senator John Sherman Cooper. McConnell describes the glamorous Republican moderate as “the first truly great man I’d ever met.” Cooper socialized in Georgetown with the Kennedys, and the press praised him for following his conscience instead of Kentucky polls. He backed the Civil Rights Act and opposed the Vietnam War, telling McConnell that there were times to follow the herd and times to go your own way.

In those days, McConnell opposed the war himself. Nevertheless, in 1967, after graduating from the University of Kentucky’s law school, he began serving in the Army Reserve, because, he acknowledges, it was smart politically. Five weeks later, he obtained a medical discharge, for an eye condition. McConnell has claimed that he “used no connections” to get out. But, soon after he enlisted, his father contacted Senator Cooper, who intervened with the commanding officer at McConnell’s base. Records show that Cooper pressured the Army to move quickly, suggesting that McConnell had immediate academic plans: “Mitchell anxious to clear post in order to enroll NYU.” He never enrolled.

Instead, McConnell began his political climb. It started poorly. In 1971, he ran for the state legislature, but he was disqualified because he didn’t meet the residency requirements. He vowed never again to ignore the fine print, and has since become a master of the Senate’s arcane rules.

In 1973, during the Watergate scandal, McConnell wrote an op-ed in the Louisville Courier-Journal denouncing the corrupting influence of money on politics as “a cancer,” and demanding public financing for Presidential elections. To read the op-ed now is head-spinning, given his current views. On closer examination, though, there is a consistency to his flip-flop. His call for reform reflected the political consensus after Nixon’s disgrace. In other words, the anti-corruption position he took in 1973 was in his political self-interest, just as his embrace of big money has been in recent decades. As he confessed to Dyche, his biographer, the op-ed was merely “playing for headlines.” McConnell, planning to run for office as a Republican, wanted to clear his name of Nixon’s tarnish.

McConnell had been hired by a Kentucky law firm, but he found it dull. In Louisville, he became friends with the sister of the Deputy Attorney General, Laurence Silberman, and in 1976 he used the connection to get a job working for Silberman in D.C., as Deputy Assistant Attorney General. The experience appears to have influenced his thinking about money in politics and much else. He became an acolyte of Silberman and two other towering figures of conservative jurisprudence then at the Justice Department: Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia.

After Watergate, Congress had cracked down on political money by imposing strict limits on campaign contributions and spending, and created the Federal Election Commission to enforce the new laws. But conservatives, as well as a few liberal groups, including the A.C.L.U., began to litigate against the reforms. James Buckley, a conservative New York senator, challenged the spending limits as an infringement of his ability to pay for political communication, and thus a violation of his right to free speech.

The case, Buckley v. Valeo, went to the Supreme Court, and Buckley won. It marked the beginning of a forty-year, largely right-wing assault on efforts to keep private interests from corrupting American politics. Charles Koch, the arch-conservative billionaire oil refiner from Kansas, who was intent on using his fortune to seize control of American politics, was an early champion of the cause. McConnell adopted the “Money is speech” idea as his own, and eventually became the country’s most relentless proponent of more money in politics. John Cheves, a reporter for the Lexington Herald-Leader, has described a class that McConnell taught in the seventies, at the University of Louisville. On a blackboard, he wrote down the three things he felt were necessary for success in politics: Money. Money. Money.

In 1977, McConnell ran for the position of Jefferson County judge / executive, the official overseeing the county that encompasses Louisville. A contemporary news account documents that, after announcing his candidacy, he promised to limit his campaign spending. But Mike Ward, who had elicited the pledge as the chair of Common Cause Kentucky, told me, “He snookered me.” Ward says that he thought McConnell meant to limit spending throughout the campaign, but McConnell’s promise applied only to the primary, in which he had no serious opponent. In the general election, he spent a record amount—and won.

Ward, a Democrat who was later elected to Congress, suggests that McConnell’s first campaign was misleading in other ways. Unlike much of Kentucky, Louisville is a Democratic stronghold. “We’re a moderate community, so to get elected he masqueraded as a progressive,” Ward said. To win the endorsement of labor unions, McConnell pledged to support collective bargaining for public employees, an issue he dropped after taking office. Years later, he admitted to Dyche that he’d been “pandering.” Abortion-rights groups believed that McConnell was on their side, but he claims that they were mistaken. Ever since then, he has called himself “pro-life,” and has packed the courts with judges who oppose Roe v. Wade. According to two people who have been close to McConnell, he attends church but isn’t especially religious, nor does he care about abortion; but, as one of the sources put it, he “will never take any position that could lose him an election.”

The race for county judge / executive got ugly. McConnell’s Democratic opponent, Todd Hollenbach, was then in the midst of a divorce, and Hollenbach told me that McConnell “made an issue of my family life.” McConnell’s spokesman denies this, but Dyche’s biography describes McConnell “calling attention to his opponent’s domestic life” with an ad describing himself as “a lucky guy” with “a great wife and two kids.” Once McConnell was elected, according to two sources, he made a sexual advance toward one of his female employees. Although his spokesman says that this didn’t happen, one of the sources told me, “It’s the God’s honest truth.” Yet McConnell’s first press secretary, Meme Runyon, praised him for hiring a number of young women, including her, and giving them career-making professional opportunities.

Three years after defeating Hollenbach, though, McConnell, amid accusations of infidelity, got divorced himself. He soon began searching for a new spouse. Keith Runyon, Meme’s husband and a former editorial-page editor of the liberal Louisville Courier-Journal, vividly recalls him showing up at their house for dinner badly sunburned after a day of campaigning at a fish fry. McConnell, who has limited patience for such glad-handing, confided a plan. Runyon recalls him saying, “One of the things I’ve got to do is to marry a rich woman, like John Sherman Cooper did.” Runyon added, “Boy, did he ever.”

McConnell’s spokesman disputes Runyon’s account, but, in 1993, McConnell married Elaine Chao, [above] an heiress, who is currently serving as Trump’s Secretary of Transportation. McConnell devotes a chapter of his autobiography to “Love,” describing how he and Chao, who emigrated from Taiwan as a child, are “kindred spirits.” He explains, “We both knew the feeling of not fitting in, and had worked long and hard in order to prove ourselves.” Chao graduated from Harvard Business School, ran the Peace Corps, served as President George W. Bush’s Labor Secretary, and has been a director on such influential boards as those of Bloomberg Philanthropies and Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. She also brought a sizable fortune into McConnell’s life. Her father, James Chao, is the founder and chairman of the Foremost Group, a family-owned maritime shipping company, based in New York, which reportedly sends seventy per cent of its freight to China.

When McConnell presided over Trump’s impeachment trial, in which the President was accused of trying to extort Ukrainian officials into helping him smear his political rival Joe Biden, he allowed Republican senators to keep insisting that the “real” Ukraine scandal was the Biden family’s enrichment from their connections with the country’s rulers. Yet McConnell must have known that virtually any criticism one could make about the Biden family could be made as well about the Chao family. In fact, such criticisms had been made in the book “Secret Empires,” by the conservative writer Peter Schweizer. Republicans who promoted the book’s accusations against the Biden family evidently skipped the adjoining chapter on McConnell and the Chao family.

As the Times has documented, McConnell and his in-laws have benefitted from unusual connections in Beijing. One of James Chao’s schoolmates was Jiang Zemin, who later became China’s President. According to the paper, James took a stake in a state-run company closely associated with Jiang. James and his daughter Angela, the chairman and C.E.O. of the family business, have also been on the boards of directors of some of China’s most powerful state-run businesses, including the Bank of China. Moreover, both Angela and her father have been on the board of a holding company that oversees China State Shipbuilding, which builds warships for the Chinese military. Angela Chao told the Times, “I’m an American,” and suggested that nobody would question the business “if I didn’t have a Chinese face.”

|

| Jim Breyer and Angela Chao |

McConnell’s marriage also made him kin to some of the most influential businessmen in America. Angela Chao [above] was married to the investment banker Bruce Wasserstein, who died in 2009, and she’s now married to Jim Breyer, [above] a billionaire venture capitalist with huge financial interests in China. In 2016, Breyer joined the board of directors of Blackstone, giving McConnell a brother-in-law at a company that financially supports his campaigns, and that manages more than half a trillion dollars.

Chao family members were campaign donors of McConnell’s even before his marriage to Elaine. According to the Times, over the years the family has given more than a million dollars to McConnell’s campaigns or pacs tied to him. Furthermore, disclosure forms show that, after Elaine Chao’s mother died, in 2007, the family gave her and McConnell as much as twenty-five million dollars, making McConnell one of the Senate’s wealthiest members.

It can be a danger for affluent Washington insiders to appear out of touch, and Kentucky is one of America’s poorest states. McConnell and members of his staff have berated the home-town paper for running a photograph of him in a tuxedo. McConnell owns a modest house in Louisville, and at home he makes a habit of doing everyday errands himself, such as shopping for groceries at a nearby Kroger. He attends local college sports events with a few old friends; they wear headphones, to follow the plays on the radio, and high-five one another when their team scores. Chao has been less vigilant about playing down her wealth. When she directed the Peace Corps, she stirred talk by arriving at work in a chauffeured car. At the Labor Department, the Times reported, she “employed a ‘Veep’-like staff member who carried around her bag.” A luxury beauty-and-fitness purveyor in Washington told me that she couldn’t get her staff to continue providing services for Chao after Chao knocked a makeup brush out of a beautician’s hand during one appointment and threw a brush on the floor during another. Kentucky Democrats have tried to make an issue of the couple’s wealth. Outside of Berea, a billboard featuring a giant photograph of McConnell and Chao is accompanied by the words “We’re rich. How y’all doin?”

From the earliest days of McConnell’s political life, he has had questionable relationships with moneyed backers. His salary as county judge / executive was meagre, and, in an arrangement that troubled some in the community, a group of undisclosed Louisville business leaders quietly threw in extra pay, ostensibly for his giving speeches. David Ross Stevens, who briefly served as McConnell’s special assistant, told me, “It was like the big boys got together and gave him a pool of money.” Stevens said of McConnell, “He was the most shallow person in politics that I’d ever met. At our first staff meeting, McConnell said, ‘Does anyone have a project for me? I haven’t been on TV for eleven days.’ He was very clever, but it was all about ‘What’s this going to do for me?’ ” Stevens quit in disgust.

Two years into McConnell’s tenure as county judge / executive, the Courier-Journal ran a story chronicling other turnover on his staff. Employees griped, anonymously, that McConnell was “extraordinarily selfish” and surrounded himself only with “yes men.” They also complained of being pressured to commit to donating their kidneys, because McConnell was chairing a National Kidney Foundation fund-raising drive. McConnell denied that his office had poor morale—and two staffers who defended him in the article continued to work with him for decades. In the Senate, he is known for cultivating a smart and loyal staff, and for maintaining a formidable network of political allies, in Washington and in Kentucky. James Carroll, the former Washington correspondent for the Courier-Journal, told me, “It’s a version of patronage—when you leave his office, he helps you in your career. Because of that loyalty, he has a vast network of eyes and ears. There are Mitch McConnell galaxies and solar systems.” One former Senate colleague of his, Chris Dodd, a Democrat from Connecticut, told me that McConnell is one of the only senators who also runs party politics back in his home state.

As McConnell gained power, Louisville’s liberal élites, including the wealthy Bingham family, which owned the Courier-Journal, grew disenchanted. The paper had endorsed him as county judge / executive, and therefore felt some responsibility for having launched him. Runyon, the former editorial-page editor, said, “He managed to get our endorsement by being what we thought was a sincere reformer.” Runyon recalled that in 2006, as Barry Bingham, Jr., the paper’s publisher, lay dying, “he had a frank talk with me—he said, ‘You know, Keith, the worst mistake we ever made was endorsing Mitch McConnell.’ ”

|

| Larry McCarthy |

In 1984, McConnell ran for the Senate against the Democratic incumbent, Walter (Dee) Huddleston. McConnell later admitted that he’d begun planning his campaign the moment he’d been sworn in as county judge / executive. Nobody expected an unprepossessing, little-known local official to defeat Huddleston, but in the final weeks of the campaign McConnell surged to an upset victory, thanks, in large part, to a television ad created by Roger Ailes, the Nixon media adviser who later became the mastermind behind Fox News. Ailes was helped by Larry McCarthy, [above] a virtuoso of negative campaign ads who later made the racially charged Willie Horton ad, attacking the 1988 Democratic candidate for President, Michael Dukakis. The McConnell ad depicted a pack of bloodhounds frantically hunting for Huddleston, ostensibly because he’d missed so many Senate votes while off giving paid speeches. It was funny, but Huddleston’s attendance record, ninety-four per cent, wasn’t out of the ordinary, and his speeches violated no Senate rules. Yet, as McCarthy proudly told the Washington Post, “It was like tossing a match on a pool of gasoline.” That year, McConnell was the only Republican who defeated an incumbent Democratic senator. Two years after criticizing Huddleston’s outside speaking fees, McConnell went on a lucrative eleven-day speaking tour of the West Coast. (McConnell’s spokesman says, “The Leader never missed a vote.”)

In 1990, Ailes helped McConnell paint his Democratic challenger, Harvey Sloane, as a dangerous drug addict. Television ads showed images of pill containers as a narrator warned of Sloane’s reliance on “powerful,” “mood-altering” “depressants” that had been prescribed “without a legal permit.” Sloane, an Ivy League-educated doctor whom McConnell mocked as “a wimp from the East,” had gone to Kentucky through a federal program that provides medical services to the rural poor, and went on to become Louisville’s mayor. During the Senate campaign, Sloane, who had postponed a hip replacement until after the election, renewed a prescription for sleeping pills although his license had expired. It was a real lapse in judgment, but he didn’t have a drug problem. Sloane said of McConnell’s attack, “It was craven. He’s just a conniving guy. He’s the Machiavelli of the twenty-first century.” McConnell himself has summarized his approach to campaigns simply: “If they throw a stone at you, you drop a boulder on them.”

|

|

Television airtime and top media consultants aren’t cheap. McConnell’s Senate campaigns further convinced him that his old op-ed opposing political money was wrongheaded. “I never would have been able to win my race if there had been a limit on the amount of money I could raise and spend,” he writes in his autobiography. Larry Forgy, a Kentucky Republican who fell out with McConnell, said that this was certainly true. “He knows without a definite advantage in money, he’s not going anywhere in politics,” Forgy said, in “The Cynic,” Alec MacGillis’s deeply researched 2014 biography of McConnell. “Politics in small Southern states requires a certain amount of showmanship, and he just didn’t have the ability to do that.”

Most politicians find fund-raising odious, but Alan Simpson, the former Republican senator from Wyoming, who served a dozen years with McConnell, told MacGillis that fund-raising was “a joy to him,” adding, “He gets a twinkle in his eye and his step quickens. I mean, he loves it.” McConnell’s donors have found themselves rewarded. Kelly Craft, the wife of Joe Craft, one of McConnell’s major backers—a coal magnate and the president of Alliance Resource Partners—currently serves as Ambassador to the U.N., after serving earlier in the Trump Administration as Ambassador to Canada. The U.N. appointment, especially, drew criticism, because her only expertise was fund-raising. A Kentuckian acquainted with the Crafts noted that the U.N. seat was once filled by such titans as Adlai Stevenson and Daniel Patrick Moynihan. “It’s just incredible,” he says.

|

| Former Massey CEO Donald Blankenship |

According to “60 Minutes,” McConnell and Chao helped another coal company skirt responsibility for one of the biggest environmental disasters in U.S. history. In 2000, Jack Spadaro, an engineer for the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration, began conducting an investigation in Martin County, Kentucky, after a slurry pond owned by Massey Energy [CEO Donald Blankenship, above] burst open, releasing three hundred million gallons of lavalike coal waste that killed more than a million fish and contaminated the water systems of nearly thirty thousand people. Spadaro and his team were working on a report that documented eight apparent violations of the law, which could have led to charges of criminal negligence and cost Massey hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines. But, that November, George W. Bush was elected President, and he soon named Chao his Labor Secretary, giving her authority over the Mine Safety and Health Administration. She chose McConnell’s former chief of staff, Steven Law, as her chief of staff. Spadaro told me, “Law had his finger in everything, and was truly running the Labor Department. He was Mitch’s guy.” The day Bush was sworn in, Spadaro was ordered to halt his investigation. Before the Labor Department issued any fines, Massey made a hundred-thousand-dollar donation to the National Republican Senatorial Committee. McConnell himself had run the unit, which raises funds for Senate campaigns, between 1997 and 2000.

Massey ended up paying only fifty-six hundred dollars in federal fines. Law went on to run a cluster of outside money groups, including the Senate Leadership Fund, One Nation, American Crossroads, and Crossroads GPS, which have collectively given millions of dollars to the Senate campaigns of McConnell and other Republicans.

A spokesman for Chao says that the department levied many more fines on coal mines during her tenure, and that “she was always concerned about coal miners’ jobs as well as their health and safety.” But Spadaro told me he has no doubt that McConnell “made sure the report was essentially suppressed.” He noted, “Massey gave a lot of money to McConnell over the years. McConnell’s very bright. He took the money and, in return, protected the coal industry. He’s truly the most corrupt politician in the U.S.” Records show that, between 1990 and 2010, McConnell was the recipient of the second-largest amount of federal campaign donations from people and pacs associated with Massey. And when McConnell ran the National Republican Senatorial Committee it took in five hundred and eighty-four thousand dollars from the coal industry.

Nina McCoy, a retired teacher who lives in Martin County, told me, “Our own senator’s wife basically shut down the investigation. Our community from then on knew all those people protected the coal companies instead of us.”

According to the Lexington Herald-Leader, in 2002, Bob Murray, the C.E.O. of another coal company, Murray Energy, shouted down a Mine Safety and Health Administration inspector in a meeting by observing, “Mitch McConnell calls me one of the five finest men in America, and the last I checked he was sleeping with your boss.” Both Murray and McConnell disputed the report, which was based on interviews and notes from the meeting. Records showed that Murray and his company’s pac had donated repeatedly to McConnell’s campaigns.

Two decades since the Massey slurry-pond disaster, the coal industry has collapsed, barely employing five thousand people statewide, but the region’s water remains tainted. McConnell takes credit for recently delivering several million dollars in federal funds to the area for water-infrastructure improvements, but William Brandon Halcomb, a property manager who lives there, told me that the situation is still “horrible.” Shortly before we spoke, there had been no water for three weeks. He keeps a bucket tied to a bridge, which he lowers into the creek below when he needs water to flush a toilet. He must drive to another county to buy clean water. “You get a gallon, heat it on the stove, and take a trucker’s bath,” he said. “A wash-off is all you can do.” As covid-19 spreads, the health hazards posed to Americans who can’t reliably wash their hands are obvious.

Martin County is overwhelmingly Republican and pro-Trump, and many residents see no connection between their problems and Washington. Gary Ball, the editor of the Mountain Citizen, a local newspaper, told me, “It’s not McConnell’s fault that our water is in bad shape.” Ball, a former coal miner who strongly backs Trump, blames local Democratic officials for “years of mismanagement.” Cara Stewart, the chief of staff for the Kentucky House Democrats, unsurprisingly sees it differently. “Why does Kentucky not have clean, reliable water?” she said. “McConnell could help, but he’s in bed with the companies that are causing the problems.”

As a backbench senator, McConnell used his fund-raising talents to rise in the Party’s leadership—a path laid out by Lyndon Johnson. Robert A. Caro, the author of a magisterial four-volume biography of Johnson, told me that, “in a stroke of genius,” Johnson, as a Democratic junior congressman, “realizes he has no power, but he has something no other congressman has—the oilmen and big contractors in Texas who need favors in Washington.” By establishing control over the distribution of the donors’ money, Johnson acquired immense power over his peers. McConnell was no fan of L.B.J., however. He has described his Presidential vote for Johnson as the one he regrets most, because he so deplored Johnson’s expansion of government to fight the war on poverty—an effort launched in Martin County. In his memoir, McConnell argues that “poverty won,” proving “Washington’s overconfidence in its own ability to systematically solve complex social problems.” (Having just passed the largest public-spending program in American history, McConnell and other Republicans are scrambling to justify the about-face, with some calling the new programs “restitution” rather than welfare.)

According to Keith Runyon, McConnell was focussed on his political survival from the moment he arrived in Washington. He recalls that, the morning after McConnell was first sworn in to the Senate, McConnell told him that he would be moving to the right from then on, to keep getting reëlected. McConnell has denied saying so, but Runyon told me, “He is a flat-out liar.” Another acquaintance who has known McConnell for years said that, “to the extent that he’s conversational, he wore his ambition to become Majority Leader on his sleeve.”

McConnell envied better-known colleagues who were chased down the corridors by news reporters. He wanted to be like them, he later told Carl Hulse, a Times correspondent, who interviewed McConnell for his book “Confirmation Bias,” about fights over Supreme Court nominees. The way McConnell ended up making his name was decidedly unglamorous: blocking campaign-finance reform. Even he derided the subject as rivalling “static cling as an issue most Americans care about.” Dull as campaign financing was, it was vitally important to his peers, and to democracy. Few members wanted to risk appearing corrupt, and so they were grateful to McConnell for fighting one reform after the next—while claiming that it was purely about defending the First Amendment. According to MacGillis, behind closed doors McConnell admitted to his Senate colleagues that undoing the reforms was “in the best interest of Republicans.” Armed with funding from such billionaire conservatives as the DeVos family, McConnell helped take the quest to kill restraints on spending all the way to the Supreme Court. In 2010, his side won: the Citizens United decision opened the way for corporations, big donors, and secretive nonprofits to pour unlimited and often untraceable cash into elections.

“McConnell loves money, and abhors any controls on it,” Fred Wertheimer, the president of Democracy 21, a group that supports campaign-finance reform, said. “Money is the central theme of his career. And, if you want to control Congress, the best way is to control the money.”

Between 1984, when McConnell was first elected to the Senate, and today, the amount of money spent on federal campaigns has increased at least sixfold, excluding outside spending, more and more of which comes from very rich donors. Influence-peddling has grown from a grubby, shameful business into a multibillion-dollar, high-paying industry. McConnell has led the way in empowering those private interests, and in aligning the Republican Party with them. His staff embodied “the revolving door,” as they went from working for one of America’s poorest states to lobbying for America’s richest corporations, while growing rich themselves and helping fund McConnell’s campaigns. Money from the coal industry, tobacco companies, Big Pharma, Wall Street, the Chamber of Commerce, and many other interests flowed into Republican coffers while McConnell blocked federal actions that those interests opposed: climate-change legislation, affordable health care, gun control, and efforts to curb economic inequality.

|

|

McConnell, like L.B.J., used fund-raising to help allies and punish enemies. “What he’s done behind the scenes is apply the thing that speaks louder in Washington, D.C., than anything else—money,” Wilson, the former Republican consultant, said. “Suddenly, Susan Collins gets a bridge in Maine. Lisa Murkowski suddenly gets a harbor. Oh, what a coincidence!” McConnell has a brilliant grasp of his caucus members’ needs, and he helps them protect their seats with tens of millions of dollars in campaign donations and federal grants, some of which come through Chao’s Department of Transportation. (A department spokesman says that there is no political linkage, and that every state gets some money.) McConnell also lets his caucus members take the spotlight, and, when he can, he allows them to skip votes that will be unpopular with their constituents. In private, McConnell can be bitingly funny, as well as sentimental—he has been known to tear up over an aide’s departure—but he is shrewdly guarded, reportedly subscribing to the maxim “You can’t get in trouble for what you don’t say.” He takes care to cover his tracks, putting private notes in his pocket rather than tossing them into Senate wastebaskets. And he protects his allies. In 2013, McConnell’s lieutenants—who are known as Team Mitch—established a policy of blackballing anyone who works against an incumbent member of his caucus. Recently, in a Georgia Senate race, consultants working for the Republican congressman Doug Collins were warned that they would be frozen out for helping him challenge Kelly Loeffler, the incumbent, who is McConnell’s choice in the primary, despite recent accusations against her of insider trading. (Loeffler denies wrongdoing.) Insubordination can result in what a former Trump White House official calls the Death Penalty: the President is told that the miscreant will not be confirmed by the Senate for any Administration job.

McConnell’s iron control has won praise from other Republicans. Chris Christie, the former governor of New Jersey, told me, “He’s the most talented Majority Leader since Lyndon Johnson. He knows how to count the votes, when to push, and when to pull. He’s a real technician who knows the rules and knows his caucus.”

Caro said, “In a way, McConnell and Johnson are very similar. They both used the rules and procedures of the Senate with great deftness. But, in a more significant way, they couldn’t be more diametrically opposite. Johnson, for all his faults, in his later years used the rules and procedures to turn the Senate into a force to create social justice. McConnell has used them to block it.”

Under McConnell’s leadership, as the Washington Post’s Paul Kane wrote recently, the chamber that calls itself the world’s greatest deliberative body has become, “by almost every measure,” the “least deliberative in the modern era.” In 2019, it voted on legislation only a hundred and eight times. In 1999, by contrast, the Senate had three hundred and fifty such votes, and helped pass a hundred and seventy new laws. At the end of 2019, more than two hundred and seventy-five bills, passed by the House of Representatives with bipartisan support, were sitting dormant on McConnell’s desk. Among them are bills mandating background checks on gun purchasers and lowering the cost of prescription drugs—ideas that are overwhelmingly popular with the public. But McConnell, currently the top recipient of Senate campaign contributions from the pharmaceutical industry, has denounced efforts to lower drug costs as “socialist price controls.”

Longtime lawmakers in both parties say that the Senate is broken. In February, seventy former senators signed a bipartisan letter decrying the institution for not “fulfilling its constitutional duties.” Dick Durbin, of Illinois, who has been in the Senate for twenty-four years and is now the second-in-command in the Democratic leadership, told me that, under McConnell, “the Senate has deteriorated to the point where there is no debate whatsoever—he’s dismantled the Senate brick by brick.” McConnell was the Minority Leader from 2006 to 2014. After Barack Obama was elected in 2008, McConnell used the filibuster to block a record number of bills and nominations supported by the Administration. As Majority Leader, he has control over the chamber’s schedule, and he keeps bills and nominations he opposes from even coming up for consideration. “He’s the traffic cop, and you can’t get through the intersection without him,” Durbin said.

Norman Ornstein, a political scientist specializing in congressional matters at the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute, told me that he has known every Senate Majority Leader in the past fifty years, and that McConnell “will go down in history as one of the most significant people in destroying the fundamentals of our constitutional democracy.” He continued, “There isn’t anyone remotely close. There’s nobody as corrupt, in terms of violating the norms of government.”

The most famous example of McConnell’s obstructionism was his audacious refusal to allow a hearing on Merrick Garland, whom Obama nominated for the Supreme Court, in 2016. When Justice Antonin Scalia unexpectedly died, vacating the seat, there were three hundred and forty-two days left in Obama’s second term. But McConnell argued that “the American people” should decide who should fill the seat in the next election, ignoring the fact that the American people had elected Obama. As a young lawyer, McConnell had argued in an academic journal that politics should play no part in Supreme Court picks; the only thing that mattered was if the nominee was professionally qualified. In 2016, though, he said it made no difference how qualified Garland, a highly respected moderate judge, was. Before then, the Senate had never declined to consider a nominee simply because it was an election year. On the contrary, the Senate had previously confirmed seventeen Supreme Court nominees during election years and rejected two. Nevertheless, McConnell prevailed.

He has since vowed to fill any Supreme Court vacancy that might open this year, no matter how close to the election it is. Indeed, according to a former Trump White House official, “McConnell’s telling our donors that when R.B.G. meets her reward, even if it’s October, we’re getting our judge. He’s saying it’s our October Surprise.”

McConnell has pointed to his obstruction of Garland with pride, saying, “The most important decision I’ve made in my political career was the decision not to do something.” Many believe that, in 2016, the open Court seat motivated evangelical voters to overlook their doubts about Trump, providing the crucial bloc that won him the Presidency.

But McConnell’s predecessor as Majority Leader, the retired Democratic senator Harry Reid, of Nevada, accuses McConnell of destroying norms that fostered comity and consensus, such as the restrained use of filibusters. Although the two leaders had at first managed to be friendly, bonding over their shared support for Washington’s baseball team, the Nationals, they became bitter antagonists during the Obama Administration. “Mitch and the Republicans are doing all they can to make the Senate irrelevant,” Reid told me. “We’ve watched them stand mute no matter what Trump does. They have lost their souls. From a policy perspective, it’s awful. It’s hurt the Senate and damaged the country.”

The costs of the Senate’s dysfunction stretch in all directions, and include America’s vulnerability in the face of the covid-19 outbreak. For seven years after Obama’s signature domestic achievement, the Affordable Care Act, passed, in 2010, Republicans in Congress tried at least sixty times to repeal it. In 2017, McConnell, who called it “the worst bill in modern history,” led the charge again and, among other things, personally introduced a little-noticed amendment to eliminate the Prevention and Public Health Fund at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which provided grants to states for detecting and responding to infectious-disease outbreaks, among other things. The fund received approximately a billion dollars a year and constituted more than twelve per cent of the C.D.C.’s annual budget. Almost two-thirds of the money went to state and local health departments, including a program called Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases, in Kentucky.

Hundreds of health organizations, including the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, sent a letter to McConnell and other congressional leaders, warning them of “dire consequences” if the Prevention Fund was eliminated. Public-health programs dealing with infectious-disease outbreaks had never been restored to the levels they were at before the 2008 crash and were “critically underfunded.” The letter concluded, “Eliminating the Prevention Fund would be disastrous.”

In a column in Forbes, Judy Stone, an infectious-disease specialist, asked, “Worried about bird flu coming from Asia? Ebola? Zika? You damn well should be. Monitoring and control will be slashed by the Senate proposal and outbreaks of illness (infectious and other) will undoubtedly worsen.” The cuts, she wrote, were “unconscionable—particularly given that the savings will go to tax cuts for the wealthiest rather than meeting the basic health needs of the public.”

On July 28, 2017, a dramatic thumbs-down vote by Senator John McCain stopped Senate Republicans from eliminating the entire Affordable Care Act, including money for the Prevention Fund. McConnell and other Republicans subsequently tried again to gut the C.D.C. fund. Much of the funding survived, although some of it was later shifted, with bipartisan support, to cancer research and other activities. McConnell’s attempt to kill the fund was just a small piece of the Republicans’ much larger undermining of Obamacare. According to Jeff Levi, a professor of public health at George Washington University, one result of the Republicans’ efforts is that many Americans who lack insurance “will likely avoid getting tested and treated for covid-19, because they fear the costs.”

McConnell’s opposition to Obama was relentless. In 2010, the Senate Majority Leader famously said, when asked about his goals, “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term President.” Carroll, the Courier-Journal reporter, was dumbstruck by McConnell’s attitude when the Senator allowed him to listen in one day as he took a phone call from Obama, on the condition that Carroll not write about it. “McConnell said a couple of words, like ‘Yup,’ ‘O.K.,’ and ‘Bye,’ but he never said, ‘Mr. President,’ ” Carroll recalls. “There was just a total lack of respect even for the office.” McConnell preferred to deal with Obama’s Vice-President, Joe Biden. (In his autobiography, McConnell mocks Biden’s “incessant chatter” but also says, “We could talk to each other.”)

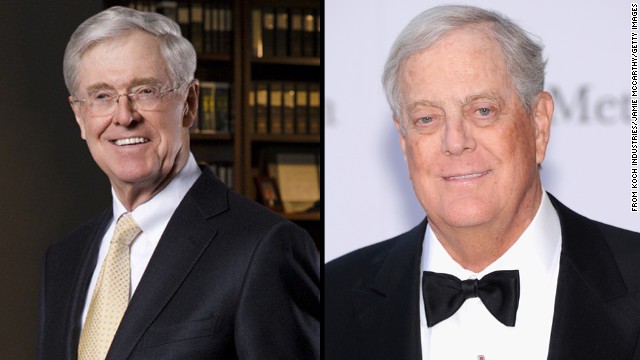

McConnell’s disrespect for Obama mirrored the views of rich conservative corporate donors like the Kochs, who underwrote many of the campaigns that enabled Republicans to capture the majority in the House of Representatives in 2010, and in the Senate four years later. In the 2014 midterm elections alone, the Koch donor network, which has a few hundred members, spent more than a hundred million dollars. In 2014, shortly before Republicans took the Senate, McConnell appeared as an honored guest at one of the Kochs’ semi-annual fund-raising summits. He thanked “Charles and David,” adding, “I don’t know where we would be without you.” Soon after he was sworn in as the Senate Majority Leader, he hired a former lobbyist for Koch Industries as his policy chief. McConnell then took aim at the Kochs’ longtime foe the Environmental Protection Agency, urging governors to disobey new restrictions on greenhouse gases.

Eager though McConnell was to see the end of the Obama era, he wasn’t enthused about Trump’s candidacy. To the extent that McConnell had any fixed ideology, he was an old-fashioned deficit hawk who favored big business, free trade, and small government—the opposite of Trump’s populist pitch.

Trump’s anti-Washington supporters weren’t enthused about McConnell, either. They booed him when he briefly appeared onstage at the Republican National Convention. But McConnell—having watched Senate colleagues from the Republican establishment, including Bob Bennett, of Utah, and Dick Lugar, of Indiana, get toppled by Tea Party insurgents—knew that it was dangerous to cross his party’s base.

In the closing weeks of the campaign, McConnell gave more assistance to Trump than many knew. In the summer of 2016, while the Senate was in recess, Obama’s C.I.A. director, John Brennan, tried to contact McConnell about an urgent threat to national security. The agency had strong evidence that President Vladimir Putin of Russia was trying to interfere in the U.S. election, possibly to hinder Hillary Clinton and help Trump. But, for “four or five weeks,” a former White House national-security official told me, McConnell deflected Brennan’s requests to brief him. Susan Rice, Obama’s former national-security adviser, said, “It’s just crazy.” McConnell had told Brennan that “he wouldn’t be available until Labor Day.”

When the men finally spoke, McConnell expressed skepticism about the intelligence. He later warned officials “not to get involved” in elections, telling them that “they were touching something very dangerous,” the former national-security official recounted. If Obama spoke out publicly about Russia, McConnell threatened, he would label it a partisan political move, knowing that Obama was determined to avoid that.

As the intelligence community grew increasingly convinced that Russia had engaged in cyber sabotage, Obama struggled to get bipartisan support from the top four congressional leaders: McConnell; Paul Ryan, then the Republican Speaker of the House; Nancy Pelosi, then the ranking Democrat in the House; and Harry Reid, then the Senate Minority Leader. Finally, after Labor Day, Obama convened an Oval Office meeting during which he urged the four leaders to put out a joint statement alerting election officials across the country to the extraordinary foreign threat. According to Denis McDonough, Obama’s former chief of staff, Ryan, Pelosi, and Reid agreed to work together, but “McConnell said nothing.” The former official said, “It took weeks to get the letter.”

A previously unseen log of the private correspondence among the four leaders’ staffs shows that McConnell edited the draft, refusing to accept any of the others’ proposed changes. He was dead set against designating U.S. voting systems as “critical infrastructure” or urging election officials to seek assistance from the Department of Homeland Security. Instead, he insisted on leaving election security entirely to non-federal officials. The final statement was so muddled that a Reid aide argued, “FWIW, I’d rather do no letter at all.” Another Reid aide replied, “Me, too. But we apparently have no choice.” Finally, on September 28th, the others signed off on the McConnell draft. Instead of identifying Russia, or a foreign threat, it merely mentioned “malefactors” seeking to “disrupt the administration of our elections.” It was so indecipherable that neither the public nor election officials learned until well after the election that Russia had targeted voting systems in all fifty states. Reid told me, “The letter was nothing like what Obama wanted. It was very, very weak.”

“I don’t know for sure why he did it,” Rice said. “But my guess, particularly with the benefit of hindsight, is that he thought” calling out Russia “would be detrimental to Trump—so he delayed and deflected. It’s disgraceful.” Rice noted that after the election McConnell continued to resist numerous bipartisan calls to safeguard election security. Only after critics began mocking him as Moscow Mitch did he finally agree, last September, to support major expenditures on it. The nickname provoked the usually unflappable McConnell; he issued a response denouncing it as “McCarthyism.”

McConnell has admitted that he was as shocked as anyone the night that Trump won. But he recovered quickly, and made an unusual demand. According to one Trump transition adviser, he “promoted” his wife for Transportation Secretary, arguing that in previous Administrations she had been the department’s deputy secretary, as well as the chair of the Federal Maritime Commission. “We thought she would want the Labor Department,” the adviser said, since she had run it during the Bush years. “It was a surprise.” It also raised conflict-of-interest questions, given her family’s shipping business. “Why would she want Transportation?” the adviser said, sardonically. “She has no business in transportation, right?” But, the adviser said, the advantage of having McConnell literally in bed with the Trump Administration was obvious to all.

Chao is among the more qualified of Trump’s Cabinet officers, but she has been accused of favoring her husband’s interests—a charge that she has denied. Politico reported that a former McConnell campaign staffer working for Chao gave extra help to Kentucky grant applicants, triggering an internal investigation, which is ongoing. Unabashed, McConnell turned the accusations into a campaign ad, boasting of his ability to bring transportation projects back to Kentucky. John Hudak, a Brookings Institution expert on government spending, and the author of “Presidential Pork,” told me, “Maybe he’s taking his cues from the President. If profiting from the operations of government doesn’t matter to the President, it likely won’t matter to a Cabinet secretary or Majority Leader.”

For a brief time in 2017, McConnell showed some independence from Trump, and some conscience. He spoke out after the white-supremacist riot in Charlottesville. Although Chao stood by Trump’s lectern as he claimed that there had been “fine people on both sides,” McConnell issued a statement denouncing the “KKK and neo-nazi groups,” adding that “their messages of hate and bigotry are not welcome in Kentucky, and should not be welcome anywhere in America.” Around the same time, Trump disparaged McConnell on Twitter for the Senate’s failure to overturn Obamacare, to which McConnell dismissively replied that the President, given his lack of political experience, perhaps had “excessive expectations.”

But, as they feuded, McConnell’s popularity cratered in Kentucky. Dave Contarino, a Democratic operative in the state who opposes McConnell, was polling and doing focus groups, and he told me that the Senator’s approval rating fell to seventeen per cent. His poll numbers didn’t recover until mid-2018, when he defended Trump during the Kavanaugh confirmation fight. “It rescued him with conservatives, who said that finally he was acting like a Republican and supporting our President,” Contarino said. McConnell’s defense of Trump during the impeachment trial boosted him further at home. Gary Ball, the Martin County newspaper editor, told me, “People here love Trump. McConnell’s not so popular. But we loved what McConnell did for Trump during impeachment.”

|

| Amy McGrath |

In McConnell’s reëlection race against Amy McGrath, [above] a former Marine fighter pilot, he has been trying to make Trump his virtual running mate. And now that McConnell has helped eliminate nearly all meaningful spending restraints, he can count on practically unlimited funds from billionaire donors. His campaign has already raised $25.6 million, although McGrath has raised even more. Matt Jones, a popular sports-radio host and the co-author of “Mitch, Please!,” a scathing book about McConnell, said, “The quickest way for him to be beaten is to turn on Trump.” Jones told me that he and his co-author had interviewed people in every one of Kentucky’s hundred and twenty counties, and had found only one, an elderly farmer, who was a big McConnell fan. “McConnell’s hated here,” he told me. “And Trump is loved. He has no choice but to kiss Trump’s ring.”

Until recently, McConnell’s enabling of Trump has worked well for him, if not for the country. But it has now made him complicit in a crisis whose end is nowhere in sight. As the consequences of the Trump Presidency become lethally clear, his deal looks costlier every day. The trusted Cook Political Report recently downgraded the chances that Republicans would hold their Senate majority to a fifty-fifty tossup, after conservative strategists reported widespread alarm over Trump’s handling of the pandemic.

Rick Wilson, the former Republican consultant, holds out faint hope that, if McConnell and Trump are both reëlected, McConnell will finally stand up to the President. McConnell would be in his seventh, and likely last, Senate term. He’s had triple-bypass heart surgery, and acquaintances say that his hearing is poor; last summer, he fell and fractured his shoulder. For the first time in his political career, he might no longer feel he has to act purely out of self-interest. “He could lead the resistance, and blow up the train tracks,” Wilson said.

Dick Durbin has no such illusions. “I’ve seen how this movie ends too many times,” he said, of McConnell and Trump. “They need each other too much.” ♦