Amazon Pulls Out of Planned New York City Headquarters

NY TIMES

Amazon on Thursday canceled its plans to build an expansive corporate campus in New York City after facing an unexpectedly fierce backlash from lawmakers, progressive activists and union leaders, who contended that a tech giant did not deserve nearly $3 billion in government incentives.

The decision was an abrupt turnabout by Amazon after a much-publicized search for a second headquarters, which had ended with its announcement in November that it would open two new sites — one in Queens, with more than 25,000 jobs, and another in Virginia.

Amazon’s retreat was a blow to Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio, damaging their effort to further diversify the city’s economy by making it an inviting location for the technology industry.

The agreement to lure Amazon to Long Island City, Queens, had stirred intense debate in New York about the use of public subsidies to entice wealthy companies, the rising cost of living in gentrifying neighborhoods, and the city’s very identity.“A number of state and local politicians have made it clear that they oppose our presence and will not work with us to build the type of relationships that are required to go forward,” Amazon said in a statement.

The company made its decision late Wednesday, after growing increasingly concerned that the backlash in New York showed no sign of abating and was tarnishing its image beyond the city, according to two people with knowledge of the discussions inside the company.

In recent days, Mr. de Blasio had tried to reach Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s chief executive, according to one official. But Mr. Bezos did not speak with him, nor with Mr. Cuomo.

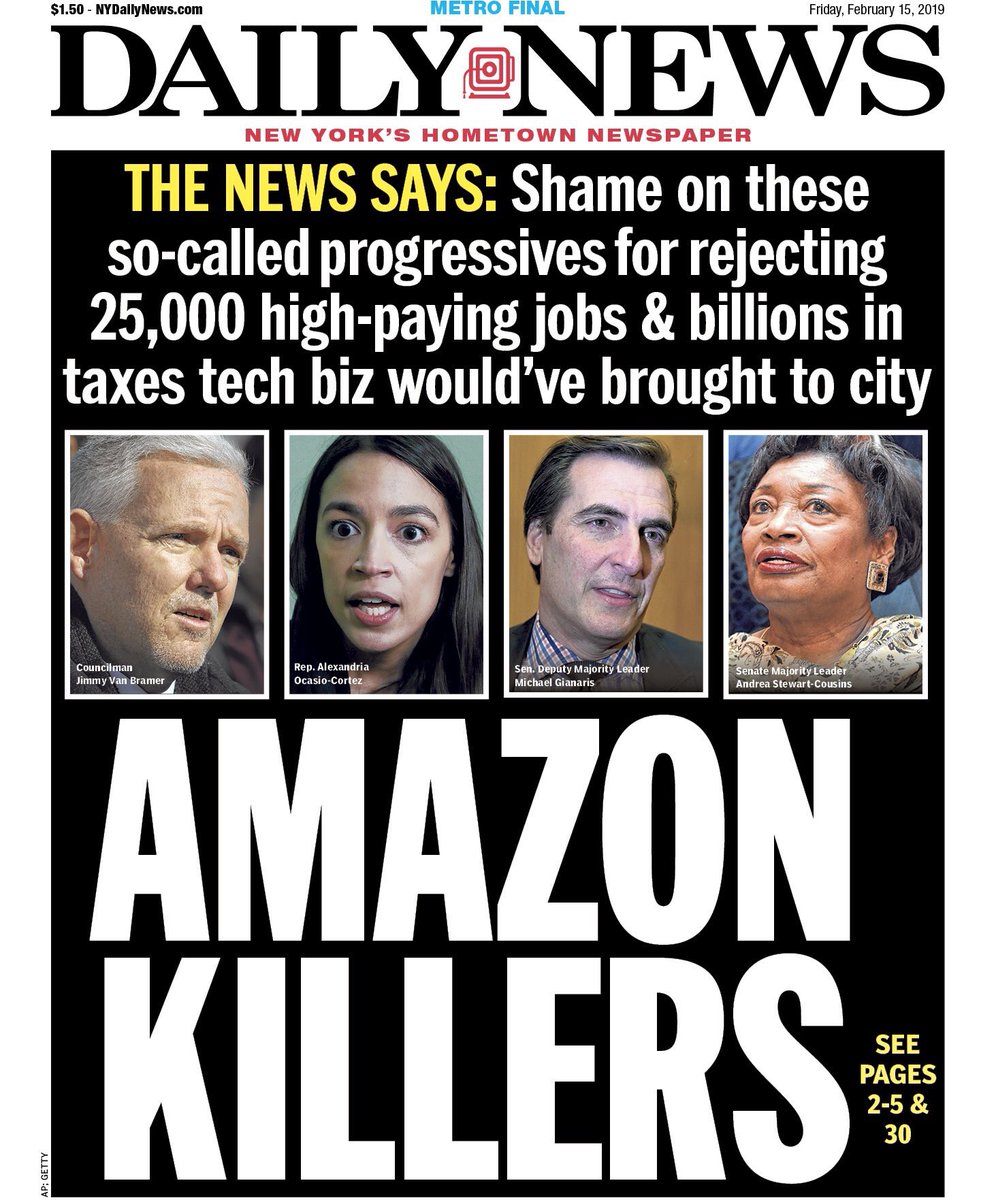

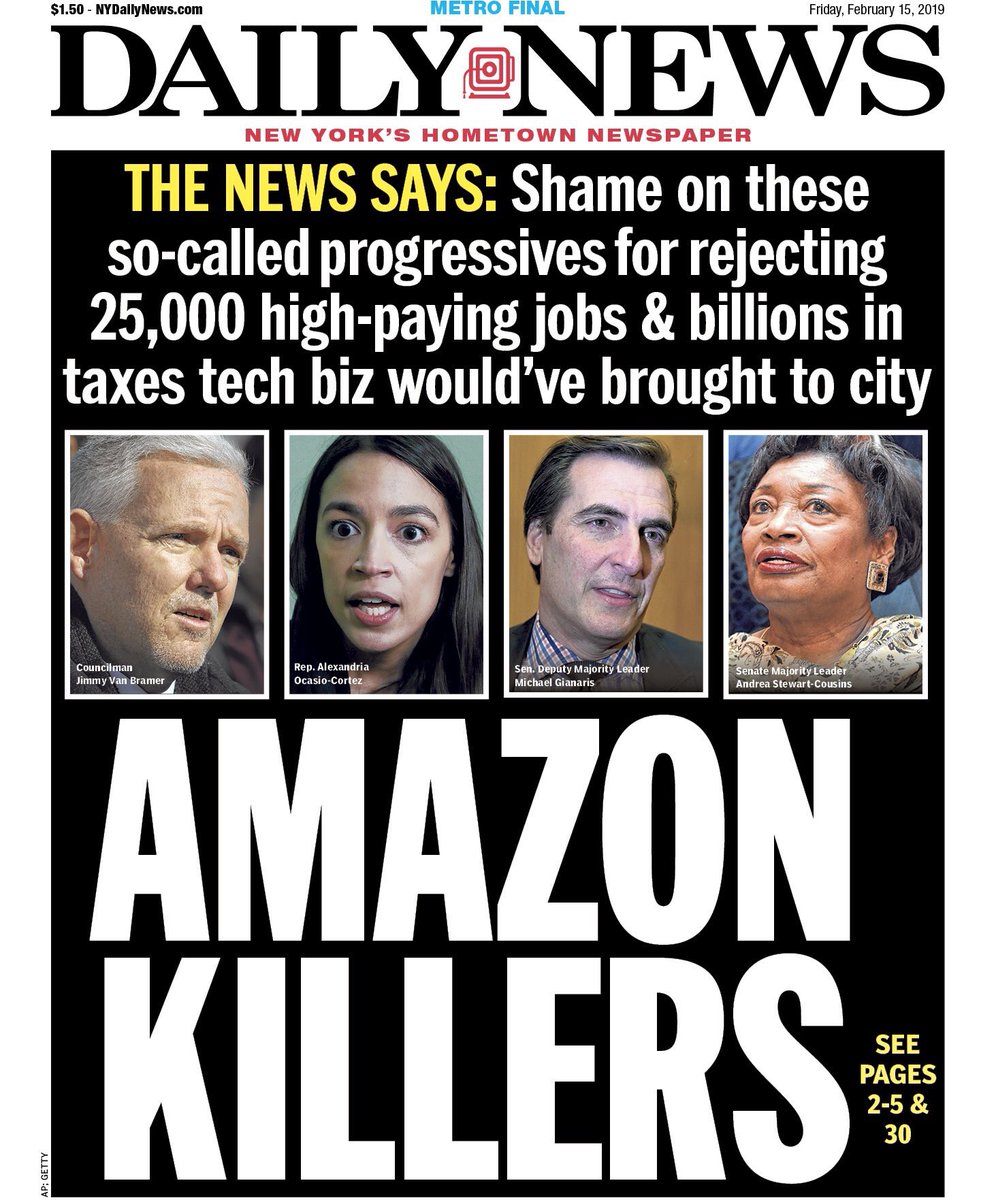

The company’s decision was at least a short-term win for insurgent progressive politicians led by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, whose upset victory last year occurred in the western corner of Queens where Amazon had planned its site.

Who's Responsible For Amazon Quitting Queens?

GOTHAMIST

NY1 political anchor Errol Louis

described it as “another case where so-called progressive politicians allowed middle-class jobs, and dreams, and hopes, to die.”

“The New York State Senate has done tremendous damage,” Governor Andrew Cuomo said in a statement. “They should be held accountable for this lost economic opportunity.”

Blame Senator Michael Gianaris And Those Loose Cannon Senate Democrats

“This is the man who delivered the death blow to Amazon deal,”

the New York Post blared above a photo of Gianaris, who represents Long Island City in the State Senate, and had led the political opposition to the company’s campus.

The Post reports that Gianaris rejected three invitations from Amazon to meet one-on-one, and that his appointment by Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins to the Public Authorities Control Board, which would need to approve the current deal for it to move forward, “put the deal over the cliff.”

|

| Andrea Stewart-Cousins, the Democratic leader in the State Senate, selected State Senator Michael Gianaris, one of Amazon’s most vocal opponents, for a board with the power to block the deal.CreditHans Pennink/Associated Press |

But Gianaris

hadn’t even taken his seat on the PACB, because Stewart-Cousins's recommendation still faced one more obstacle: Governor Cuomo’s approval. If Cuomo wanted to send a signal to Amazon that he was still in control, why not state that he would veto Gianaris and ask Stewart-Cousins for another name? (Gianaris's office did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The governor’s office declined to comment on the record for this article.)

Perhaps Cuomo didn’t want to offend Gianaris,

the powerful senator who is largely credited with the organizing strategy that swept the Senate Republicans out of office in 2018, and who he will need to pass his ambitious 2019 legislative agenda. But Gianaris was just one noisy speedbump. At some point, the Amazon plan was going to have to pass the state legislature, either in a vote to raise the monetary cap and the duration of the Excelsior Jobs Program to meet Amazon's targets, or to approve the $505 million capital grant from the state, or both.

Progressive Activists Killed The Amazon Deal

They

rallied, they canvassed, they tweeted,

they got AOC to tweet, they dropped banners during raucous City Council meetings, egged on by City Council Speaker Corey Johnson (who never officially opposed the deal) and Queens Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer (who did oppose it but apparently also took private meetings with the company). They pointed to Amazon’s anti-labor stance, its relationship with ICE, its track record in Seattle, where it

crushed the city’s effort to tax large employers in order to address its homelessness epidemic.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A group of workers at Amazon’s new Bloomfield fulfillment center have joined together with hopes of forming a union.

Employees who are seeking to form a union at the new facility cited warehouse issues, including safety concerns, inadequate pay, and 12-hour shifts as their reasons.

“Ever since they opened, management has forced everyone at the warehouse to work 12-hour shifts for five or six days a week,” said Rashad Long, who works as a picker at the new Amazon facility at a recent press conference.

She said during the new-hire orientation, management promised workers that the company would provide a shuttle service and ride shares to help workers get to and from the warehouse.

“That has not happened. Instead, we all need to rely on an overcrowded MTA select bus service. It takes me four hours every day to get to and from work,” she said.

She also cited “health and safety” issues at the facility.

“Product bins are over-stuffed, and our breaks are few and far between. The third and fourth floors are so hot that I sweat through my whole shift, even when it’s freezing cold outside,” said Long.

Employees are working with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) to launch a union.

AMAZON: ‘FALSE ALLEGATIONS'

However, Amazon said all the allegations are “false.”

“Amazon offers market-leading pay -- associates at our Staten Island facility make $17-$23 an hour -- and a great benefits package, including healthcare, pre-paid education through Career Choice, and up to 20 weeks parental leave,” said Rachael Lighty, an Amazon spokeswoman.

“We are also proud of our focus on safety, employee engagement, and open door communication culture. We firmly believe this direct connection is the most effective way to understand and respond to the needs of our workforce. We encourage anyone to compare our compensation, benefits, and workplace to other retailers, and to come take a tour and see for yourself through our public fulfillment center tours.”

She said it’s not true that employees are forced to work 12-hour shifts. “Our standard schedules are four days per week, 10 hours per day. ...We have a variety of flexible shift options and during the peak holiday season, we offer overtime for employees. ...” Lighty said.

The spokeswoman also combatted other allegations, including the promised shuttle service. “Amazon’s Staten Island fulfillment center offers associates multiple transportation options, including both public transportation and a rideshare service through 511NY RideShare," she said.

Of the alleged unsafe condition, Lightly said: "... All fulfillment centers are built with climate control; this includes our Staten Island facility. The site monitors temperature on every floor throughout the building, every single day. We keep our fulfillment center at 73 degrees F at this time of year

====================================================================

T

he Memorandum of Understanding between Amazon, the state, and the city was short on specifics: the company pledged to chip in $5 million, along with another $10 million from the city and the state, to fund “workforce development initiatives” over a ten year period, targeting students and “non-traditional demographics including NYCHA residents.” Amazon agreed to fund “semi-annual” job fairs at the Queensbridge Houses for three years. The rest was still up for negotiation. Amazon told the city that half of those 25,000 jobs wouldn’t be tech related.

No matter what, Amazon was still on track to get as much as $3 billion in tax incentives and grants from the city and state, which for a trillion-dollar company run by a man who

makes $11.5 million an hour, looks somewhat unseemly. So maybe...

It Was Those $3 Billion In Subsidies!

Despite the sticker shock, the Amazon deal itself featured few discretionary incentives aside from the $505 million the state planned on giving the company in a capital grant. Amazon was poised to get as much as $1.7 billion from the city for two tax benefits that any company could have applied for (the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program (ICAP) property tax breaks for new development and per-employee tax rebates under the Relocation and Employment Assistance Program [REAP]).

The state’s Excelsior Jobs Program tax breaks are tied to actual job creation, but any corporate applicant can receive them. Assuming the Amazon deal would have spurred an equal number of jobs from other companies and retailers in their orbit, the total subsidy amount per job worked out to around $55,000, which is

par for the course across the country.

In their editorial, the Times warns of the consequences of spurning Amazon “if New York gets a reputation for the smugness of its politicians and their hostility to business.”

Hostility to business? A 2015 study by the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research showed that New York was second in the nation to New Mexico (and above Louisiana) in corporate incentives. Just last week, the Citizens Budget Commission reported that New York gave corporations roughly

$10 billion in economic incentives in 2018 alone, with very little real oversight.

Maybe Amazon’s Decision Was Amazon’s Decision?

Of course, Amazon could have avoided much of the state legislative intrigue, and silenced critiques of backroom dealing if they had gone through the city’s public land use review process to build their new campus, like any other developer.

But Mayor Bill de Blasio, who pushed for the deal,

albeit tepidly, told Brian Lehrer on Friday morning that the company refused to consider it.

“If I had said, ‘Hey Amazon, you’re going to have to wait a year-and-a-half for the full land use process,’ I guarantee—guarantee—they would have said, ‘Sorry, we’re going to Virginia, we’re going to Dallas, we’re going somewhere else,” and then all of you Brian, respectfully, would have said, ‘How on Earth did you lose 25,000 to 40,000 jobs,’ so, there’s a lack of integrity in this debate, people should come to grips with it."

The mayor added that he was blindsided by Amazon’s about-face.

“To get a call after, you know, months of attempting to build a productive partnership on behalf of this city, to get a call out of the blue saying ‘see you,’ you know, ‘we're taking our ball and we’re going home,’” de Blasio said. “It’s absolutely inappropriate.”

Greg LeRoy, the executive director of

Good Jobs First, a government watchdog group that tracks state and local job subsidies, says that this kind of negotiating tactic is a hallmark of corporations plying the “tax break industrial complex.”

“An essential working part of it is to degrade and demean public officials. It’s to get them to internalize, you Hartford, you New York, you Chicago, are not worth very much. We have lots of other choices. You’ve got lots of problems. If you don’t pay us a lot of money to offset the things we don't like about you, you’re disposable.”

LeRoy added that Amazon initially had “a very strong business case for them to come to New York, and I think they really wanted to come, and then I think they really ran into a buzzsaw.”

“Their arrogance about the way they approached the deal made it much harder for them than it had to be," LeRoy said. "If they had not preempted the City Council, if they had not expected those huge as-of-right incentives from the city, if they had not wired the thing for Cuomo to just run over the City Council, and actually talked to people in the neighborhoods, things might have played out very differently."