KAREN TUMULTY, WASHINGTON POST

KAREN TUMULTY, WASHINGTON POST

A few dozen people gathered one early March evening at the National Museum of American History to celebrate the opening of a new exhibition marking the centennial of women’s suffrage.

Collected in the glass cases are the artifacts of a long, arduous road to political empowerment:

A red silk shawl worn by Susan B. Anthony as she plied the hallways of the Capitol arguing for the right to vote.

A palm-sized campaign card from the 1916 campaign of Montana’s Jeannette Rankin, who became the first woman elected to Congress.

The brown felt hat that Bella Abzug wore at the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston, where some 2,000 delegates declared: “We demand as a human right a full voice and role for women in determining the destiny of our world, our national, our families and our individual lives."

Another item on display: the gavel used to call the U.S. House to order on Jan. 4, 2007.

The speaker who wielded that gavel on that day was, for the first time, a woman. Though Nancy Pelosi does not lack for self-confidence, she rarely indulges in public self-reflection. On that night at the Smithsonian, however, she gave a nod to those who had paved the way for her.

“The women who did all of this — oh my gosh — we revere them. We hold them up as icons. But what we hear people say is, ‘Yes, they were icons. You are troublemakers.’ They were considered troublemakers in their time, so maybe there is a future for all of us,” Pelosi said with a laugh. “But I can just tell you, a troublemaker with a gavel — that’s the real difference.”

Power is not influence. Power is when you have the ability to make change. ... Being speaker of the House, that’s real power.

This troublemaker with a gavel is the highest-ranking female elected official in the nation’s history and, on Thursday, Pelosi will also mark a personal milestone: her 80th birthday. Fittingly, it comes at the end of Women’s History Month. Just as appropriately, Pelosi will be marking it by attempting a huge, complicated and vitally important legislative lift — marshaling support for a massive spending bill to blunt the impact of the coronavirus.

As the day approached, Pelosi sat down with me to talk about her unlikely rise as a woman in a male-dominated institution and the lessons she has learned along the way. She spoke with an openness and introspection that are rare for her, perhaps recognizing this as a way to better mark the trail for others.

Pelosi will be tested in the coming months, as her generationally divided party looks for a way to navigate the coronavirus crisis while regrouping behind a presidential nominee. Then, in the fall, every seat in the House will be on the ballot and, with it, Pelosi’s 35-seat majority. Voters will render judgment on her decision to press forward with President Trump’s impeachment last fall. But it is likely they will be focused more on figuring out which party can be trusted going forward, and specifically, which is better equipped to manage the next phase of the government’s response to the most challenging peacetime crisis in a century or more.

When an election looms, Pelosi is never far from the conversation. The speaker is a polarizing figure whose unfavorability in the polls consistently surpasses her positive numbers by double digits. She has been the target of thousands of Republican campaign ads, though that assault failed spectacularly in 2018, when Democrats swept the midterm elections and regained control of the House. More than a few in Pelosi’s own caucus had their doubts when she announced that she wanted her old job back. There were voices, on both the left and the right of the party, who said Pelosi’s time had passed.

But her second act has been, by some measures, even more impressive than her first. Pelosi’s discipline and maturity, her refusal to be intimidated by Trump’s bluster, have energized the Democratic base and kept a volatile and impulsive president off balance.

A few days after Trump’s inauguration, his combative chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon took the measure of the then-House minority leader at a meeting in the White House dining room. Trump had begun the session by repeating his fantastical claim that he would have won the popular vote in 2016 had it not been for millions of fraudulent ballots cast on Hillary Clinton’s behalf.

“There’s no evidence to support what you just said,” Pelosi said sharply. “And if we’re going to work together, we have to stipulate to a certain set of facts.”

“She’s going to get us,” Bannon whispered to colleagues. “Total assassin. She’s a total assassin.”

A woman about to enter her ninth decade has become a warrior-heroine to the social-media generation. It seems that her every gesture toward Trump conveys a message of contempt. When he gave his 2019 State of the Union address, she offered stiff-armed, mocking applause. Right after he delivered it this year, she gracelessly ripped up her copy of what she called “a manifesto of mistruths.”

At times, even Pelosi seems taken aback by the frenzy she can trigger. After she got the better of the president during a meeting in late 2018, the Internet was ignited by an image of her striding triumphantly from the White House in a fire-colored coat. It created such a sensation that fashion house Max Mara scrambled to put the design from its 2012 collection back on the market again for $2,990. “You know, it’s a funny thing because none of it was planned or intentional. I only wore that orange coat because it was clean,” Pelosi recalled. “Now, I can barely wear it because it’s a meme.”

She understands the significance that such moments convey, especially for many women. “When I was speaker before, I rarely paid attention to the accoutrements of power. I was just busy being a legislator. This time, people seem to know more about what the speaker is — well, for whatever reason — and maybe social media has made that clear to people,” she said. “But as I say to the women, nobody ever gives away power. If you want to achieve that, you go for it. But when you get it, you must use it.”

In nearly every major negotiation between the executive and the legislative branches, Pelosi remains the lone woman at the table where the biggest decisions are made. Still, the gains that she has seen women make over the course of her political career have been enormous. When Pelosi arrived in the House in 1987, a freshman at the age of 47, there were barely two dozen women among its 435 members. Now, in part thanks to her efforts, there are more than 100.

But even as these victories are celebrated, they remind us that no woman has yet to climb to the top. “My disappointment is that every time I’m introduced as the most powerful woman in American history, it breaks my heart because I think we should have a president,” she said. “We could have had a female president, and we should and we will.”

It is therefore instructive to recall that Pelosi’s own rise was not one that anyone — starting with the speaker herself — would have foreseen. Life has a way of making a joke of the plans that we devise for ourselves. Only in the rear-view mirror can we see how choices and chances pave a road we could never have imagined.

“Nancy Pelosi has wielded power more forcefully and effectively than any speaker since Joe Cannon,” says congressional authority Norman J. Ornstein, invoking the name of the iron-fisted Republican who ruled the House in the early 20th century. “Her assets include her public presence, her coolness under pressure, her remarkable negotiating skills and her ability to get to yes."

None of that was imaginable at the start. True, biographies of Nancy Patricia D’Alesandro Pelosi usually begin with the fact that she was born into one of Baltimore’s most storied political families. Between them, her father and her brother — both named Thomas D’Alesandro — served four terms as mayor of the city. The elder D’Alesandro also spent eight years in the U.S. House, and before that, held seats in the Maryland legislature and on the Baltimore City Council.

But while politics were woven into her DNA, other things were expected of Nancy, the youngest of six and the only girl. Her father thought that if his daughter went to college, it should be in Baltimore, so that she would continue to live under his roof. Her mother hoped Nancy would become a nun, which the devout Annunciata D’Alesandro believed was the most spiritually fulfilling life to which a woman could aspire. “Tommy was groomed to be mayor," Pelosi explained, "and I was raised to be holy.”

As a kid, Pelosi had little interest in stepping up to become part of a political dynasty. “I just wanted to be normal,” she recalled. “I saw people whose families had weekends and things like that. We were always doing political events.”

Yet the Democratic Party was as much a part of the D’Alesandro identity as its Catholic faith and its Italian roots. Portraits of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman hung on the walls of their house on Albemarle Street. “We saw our Democratic values as related to our religious values,” Pelosi said. “So it was almost a moral imperative that we would be community oriented. That didn’t mean you had to run for office. It meant you would participate in the manner that you did and help people run for office — for the candidates, the causes, the values of the Democratic Party.”

She learned to count votes early. The front room of the mayor’s home in Little Italy operated as a sort of ad hoc social services agency, where supplicants were constantly calling and showing up at the door. Nancy helped her mother curate what was known as the “favor file,” a record of everyone who had asked for and received a job, or a bed in City Hospital, or a spot in public housing, or a welfare check. The expectation was that repayment of these debts would arrive, precinct by precinct, at election time.

Nancy was a neighborhood princess, driven a mile each day to the Institute of Notre Dame by a chauffeur. Embarrassed, she insisted on being let out to walk the last block. In 1958, she competed in a citywide extemporaneous debate competition. One of the questions presented for argument was: “Do women think?”

It took a good deal of negotiation to persuade her father to allow her to move 37 miles south to attend Trinity, a women-only Catholic college in Washington. There, she felt the first stirrings of an ambition that would someday drive her. She majored in history because it was the only way she could study political science courses. As graduation approached, she began to consider applying for law school.

But while taking a summer class on Africa, she met and fell in love with a Georgetown University student named Paul Pelosi. They were married two years later, in 1963. Pelosi set aside her plans for law school and followed his career, first to New York City and then to his native San Francisco, where he made a fortune as a financier and real estate investor.

In the space of six years, from 1964 to 1970, Pelosi gave birth to four girls and a boy. Her days fell into a fast rhythm of diapers, naps and homework. She sometimes drove car pool with her nightgown on under her coat, and once sent her daughter Jacqueline to school with a braid on one side of her head and a pony tail on the other.

But her friends marveled at the discipline with which the young mother ran her full household. When it was time for dinner, she stood on her steps and rang a cowbell, bringing five little Pelosis scurrying from all directions. Once the evening dishes were done, the kids set the table for the next morning’s breakfast. They made their own school lunches from an assembly line of bread and sandwich meat.

“She knew how to be organized. She crammed a lot into one day,” recalls fellow California Rep. Anna G. Eshoo (D), a friend from back then. “Those are transferable talents to heading up the caucus. You know, people underestimate that.”

Politics was a hobby, not a career. When Pelosi lived in New York, she passed out campaign leaflets as she took her children trick or treating. In San Francisco, her large, elegant house was ideal for fundraisers. But she still couldn’t picture herself as a candidate. “No, I never had any interest. I didn’t have the ambition to do it. And I think that women today — I’m so proud of their ambition, because you have to be ambitious to run for president of the United States,” Pelosi told me. “I didn’t actually, when I got married, give up my thought of going to law school. It just turned out that I was having all these babies, being that devout Catholic that I am. And then one thing led to another.”

The one thing that led to another — and then another and another — was her appointment to a seat on San Francisco’s Library Commission in 1975. It was the first job outside her home where she served in anything other than a volunteer capacity. The following year, when a young California governor named Jerry Brown decided to run for president, she leveraged her family connections to help him win the Democratic primary in Maryland. It was one of only three states he carried.

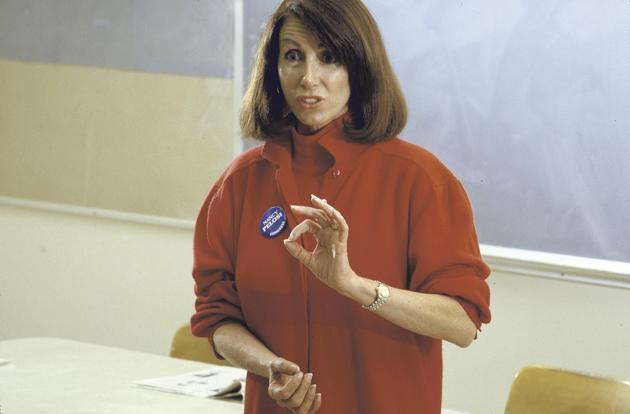

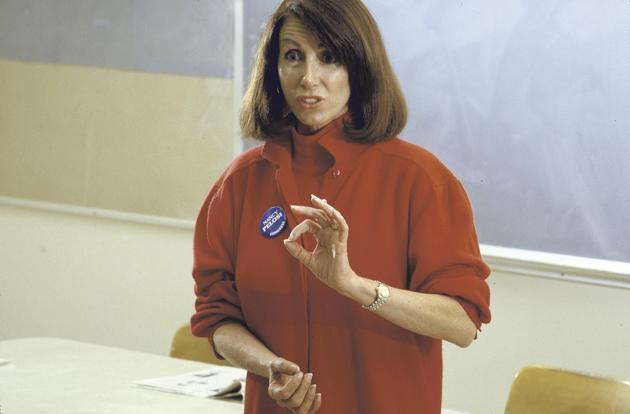

Brown repaid Pelosi by backing her in 1977 to be chairwoman of the Northern California Democratic Party. In 1981, she was elected statewide chair; she won high marks for both her fundraising and her efforts to modernize the party operations. From there, she launched the campaign that brought the 1984 Democratic National Convention to San Francisco.

An early profile in the New York Times, published during that convention, described Pelosi as “a slim woman 41 years old,” and noted that she was interviewed “in her spacious living room in the fashionable Presidio Terrace area of the city while her five teenagers put together press kits and her husband, Paul, hauled cartons of campaign buttons and posters out of the room.” Asked then whether voters might ever expect to see her name on a ballot, Pelosi dismissed the possibility: “I’m more into fundraising, but I like the vitality, the disagreements, the advocacy of politics.”

That convention is best remembered for the historic nomination of Geraldine A. Ferraro, a member of the House from New York, as presidential candidate Walter Mondale’s running mate. But Mondale and Ferraro suffered a landslide defeat that fall. The party that Republicans had begun referring to as the “San Francisco Democrats” was left in utter disarray, with a rising moderate and conservative faction demanding that it take a more centrist direction.

The factional divide spilled into the bitter 1985 race for a new national party chair. Pelosi decided to run for it, making the argument that the Democrats’ problems were rooted not in their principles or ideology, but rather, in their outdated approach to campaigning. In what would become a theme, she portrayed herself as an outsider from the future-facing West, tilting against an ossified establishment in Washington.

But many senior party figures could not see her as anything but a dizzy liberal from the Bay Area. To read the news stories about that race now is to be struck by the sexism with which she was treated. A top official of the AFL-CIO referred to her as an “airhead.” After Pelosi lost, journalist Joseph Kraft wrote that “she came on, in one news conference, as an overbearing player of feminist politics.”

... if I was called an overbearing feminist 35 years ago, I would consider that a compliment.

That latter description still amuses Pelosi. “Yeah, maybe. I certainly hope so,” she said. “One person’s insult, I take as a compliment. But that was new and this was a long time ago. ’85. What are we talking about? A long time ago. Thirty-five years ago. And if I was called an overbearing feminist 35 years ago, I would consider that a compliment.” But she acknowledged that she wasn’t prepared for the attacks: “There’s nothing as, shall we say, revealing as having an intra-party fight.”

Though she lost, the race taught Pelosi an invaluable lesson. Running for something, she discovered, can be a vicious undertaking, one where past favors are quickly forgotten and loyalty cannot be assumed. She also learned the hard way that a fist can seal a deal better than a handshake. “In many ways, it kind of changed the lens for her,” said Eshoo. “When she ran for the Democratic national chairmanship, I think that she romanticized the Democratic Party. When she ran for Congress, she knew the minefield. The minefield has nothing to do with the values and all of that. But there’s a darker side.”

Pelosi soldiered on, serving in 1985 and 1986 as finance chair of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, helping raise the money by which Democrats took back control of the Senate from the Republicans who had held it for six years. It was a rare win in a lost decade for Democrats.

The following year, Pelosi finally took the step that she had so long resisted. The decision was made for her, in a way, by the bequest of a friend who was dying. Rep. Sala Burton, the widow of one of California’s legendary kingmakers, had succeeded her husband Phil after he collapsed with a fatal aneurysm in 1983. Suffering from cancer herself, Burton summoned Pelosi to her hospital room and told her she did not plan to run for reelection. Burton asked Pelosi to run for the seat, which represents most of San Francisco.

By then, four of Pelosi’s children were out of the house, but her youngest, Alexandra, still had another year in high school. Pelosi asked her daughter’s opinion and noted that, if she won, she would have to spend three nights a week away from home in Washington. “Mother,” Alexandra replied, “get a life.”

Burton announced her support for Pelosi and died less than two weeks later. “Her endorsement was golden,” Pelosi said. So was the fact that Pelosi had the Burton machine behind her. But plenty of others, including three county supervisors, jumped into the race as well. In the crowded special election, Pelosi had to fight off charges that she was “a dilettante” who was trying to stage “a coronation.”

“These are people who are saying this for whom I had had events in my home, who I had advanced to positions, some of them, that they were in, and yet they were saying that,” Pelosi recalled, still bristling. “But I was ready. I was ready because I knew how difficult an intra-party competition is. It’s disappointing because it’s your friends.”

Pelosi made it past 13 other candidates in a squeaker of an election that went to a June 1987 runoff.

Arriving in Congress as a middle-aged House freshman, Pelosi wasn’t at all sure how long she wanted to stay. At 47, it seemed she might have missed her shot for rising through the seniority system. “I had absolutely no interest in running for leadership. None. But I did love my work,” she said. “The two [committees] that forged me were appropriations and intelligence, and I drank deeply from all of that.”

After Democrats lost the House in 1994, however, Pelosi grew increasingly frustrated with seeing her party fall short election cycle after election cycle. “I said, ‘I’m tired of losing. I don’t get this. I can’t wait for a pendulum to swing. We have to go take action,’” she said. The House’s Democratic leadership, which hadn’t added a new face to its top ranks in a decade, was happy to accept the money Pelosi brought in from California. But it didn’t care to hear her advice.

In 2000, the Democrats needed to flip only seven seats to win back a majority. Pelosi told the leaders that if they would allow her to run the campaign operation in California her way, she could pick up four in that state alone. “I know California like the back of my hand. I know the grass roots down to the last blade of grass. I know the districts. I know how different they are from each other, how different they are within the districts,” she said. “We will have the resources. We’ll make sure the candidates are a match for their districts.”

On election night, she delivered more than she had promised. Democrats added five, not four, seats in California. But in the rest of the country, they lost almost as many, which left them pretty much back where they started.

When the caucus, led by Missouri’s Dick Gephardt, held its annual retreat the following February, Pelosi stood up and made a presentation explaining how she had won in California. She argued that the party needed to sharpen its message, rev up its organization and stop being so dependent on cookie-cutter strategies devised by overpaid consultants. She believed that technology opened new opportunities to reach and raise money from the grass roots, rather than continuing to rely on traditional corporate interests.

The reaction she got: None.

Pelosi realized that if she wanted to change things, she had to muscle her way into leadership, something she had been quietly talking about with a close circle of colleagues for several years. “I had enormous respect for Dick Gephardt, who was our leader. I did. But there is a pecking order here, and you just wait in line 200 years or something,” she said. “I was tired of losing.”

It turned out that others in the House were, too. And in the best tradition of Albemarle Street, many of them owed some favors to Pelosi, who had been throwing campaign money their way. In 2001, she beat Rep. Steny H. Hoyer of Maryland and was elected Democratic whip. When Gephardt stepped down a year later, she became minority leader.

In the wake of 9/11, Republicans were on the rise again. Pundits were astonished that the House Democratic caucus would turn to a liberal from San Francisco as its leader. “Are the Democrats about to go insane?” David Brooks wrote in the Weekly Standard. “Nancy Pelosi, the presumptive House minority leader, may be the most caricaturable politician since Newt Gingrich.”

But two more cycles after that, Pelosi had her hands on that gavel that now sits in the Smithsonian.

As the culture and structure of the House has evolved over the past 100 years, so has the job of the speaker. Through much of the 20th century, speakers had to defer to committee chairmen, who ruled their own fiefs. Then, the reform-minded members elected in the wake of Watergate demanded that the House operate under more transparent, egalitarian rules. The environment within the institution has also become a greater challenge for its leaders. While the giants of the past, such as Sam Rayburn and “Tip” O’Neill, are appropriately revered, the chamber over which they presided was far less polarized and partisan than it is today. Observes Ornstein: “Pelosi has had the typical challenges with a Democratic Party with multiple wings and interests, but also has to cope with a GOP that is an insurgent outlier, scornful of compromise, that has become more of a cult than a traditional American political party.”

Newt Gingrich, one of her recent predecessors, helped produce the divisiveness that permeates the House today, but he also left Pelosi a gift. Gingrich elevated the visibility of the speakership, centralized decision-making power and stripped the committee chairs of their remaining autonomy.

By the time Pelosi became speaker, then, the office was more powerful than at any time in memory. During the first year of Barack Obama’s presidency, she marshaled her 81-seat Democratic majority to deliver practically every single legislative item on his agenda: energy, regulatory reform, education, pay equity. Then, in Obama’s second year, after the Senate became disabled with the loss of its filibuster-proof majority, it fell to Pelosi to pull off the legislative miracle that rescued the president’s signature domestic achievement, the Affordable Care Act.

All of that success, ironically enough, cost Pelosi her job. In the 2010 midterms, voters handed control of the House back to Republicans.

As part of the bargain for getting a second chance at speaker in 2019, Pelosi agreed to limit her tenure to four more years. If the party maintains its majority, she will be out by 2023, and she intends to make sure that the wait for a second female speaker is shorter than it was for the first.

I always say to people, ‘Being a woman — yes, you’re a woman. That’s self evident. Now show what else you have to offer.’

“I’ll tell you this — and sometimes I get criticized for saying it — but when I was running for whip, my first leadership position, the last thing that anybody who was supporting me could say to somebody to get his or her vote was, ‘You should vote for Nancy because she’s a woman,’” she said. “That was the biggest turnoff. Now we’re talking 19 years ago, 18 years ago. You had to just say she’s the best. She can get the job done. This is why she should be that person. So I always say to people, ‘Being a woman — yes, you’re a woman. That’s self evident. Now show what else you have to offer.’”

Pelosi is grooming a generation of female lawmakers to follow in the footsteps of her four-inch stilettos. “When women come here, I want them to be subcommittee chairs, and I’m talking about in their freshman year,” she said. “I want them all to have a security credential, whether it is armed services, foreign affairs, intelligence, veterans affairs, homeland security issues and within other committees that focus on defense, because that’s an important credential for a woman to have.”

“Women are asserting themselves in arenas that a long time ago might not have been considered a woman’s arena. But [they are] not only at the table. They have a seat at the head of the table, and it’s pretty exciting,” she added proudly. “So we’ve opened the door to have these people rise up, gain standing on their issues, more reputation. So they’re better known further down the road, should they seek higher office.”

Having had to cut her own path, Pelosi is making sure that it will be much easier for those who come after her to find their way. And perhaps, before too long, to go even further. Then the troublemaker with a gavel will finally get her wish — to no longer hear herself introduced as the most powerful woman in American history.