CATO INSTITUTE, NAT & NICK HENTOFF

It was one of the biggest riots in New York City history.

As many as 10,000 demonstrators blocked traffic in downtown Manhattan on Sept. 16, 1992. Reporters and innocent bystanders were violently assaulted by the mob as thousands of dollars in private property was destroyed in multiple acts of vandalism. The protesters stormed up the steps of City Hall, occupying the building. They then streamed onto the Brooklyn Bridge, where they blocked traffic in both directions, jumping on the cars of trapped, terrified motorists. Many of the protestors were carrying guns and openly drinking alcohol.

Yet the uniformed police present did little to stop them. Why? Because the rioters were nearly all white, off‐duty NYPD officers. They were participating in a Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association demonstration against Mayor David Dinkins’ call for a Civilian Complaint Review Board and his creation earlier that year of the Mollen Commission, formed to investigate widespread allegations of misconduct within the NYPD.

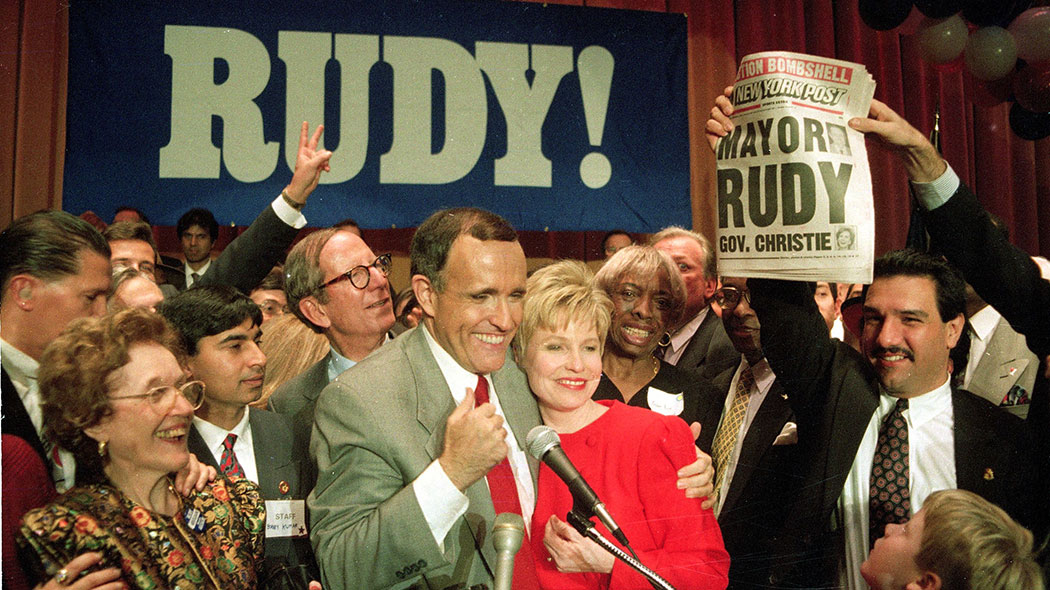

In the center of the mayhem, standing on top of a car while cursing Mayor Dinkins through a bullhorn, was mayoral candidate Rudy Giuliani.

“Beer cans and broken beer bottles littered the streets as Mr. Giuliani led the crowd in chants,” The New York Times reported.

Now, almost 25 years later, Giuliani continues to fan the flames of racial division. The two‐term mayor, who has been a prominent surrogate for presidential candidate Donald Trump and is his likely choice to head the Department of Homeland Security, recently made headlines for condemning the Black Lives Matter protests as being “anti‐American” and arguing that the term itself is “inherently racist.”

But Giuliani has yet to condemn the blatant racism that rippled through the crowd during the 1992 demonstration.

Newsday columnist Jimmy Breslin described the racist conduct in chilling detail:

Newsday columnist Jimmy Breslin described the racist conduct in chilling detail:

“The cops held up several of the most crude drawings of Dinkins, black, performing perverted sex acts,” he wrote. “And then, here was one of them calling across the top of his beer can held to his mouth, ‘How did you like the niggers beating you up in Crown Heights?’ ”

The off‐duty cops were referring to a severe beating Breslin suffered while covering the 1991 Crown Heights riots in Brooklyn.

Breslin continued: “Now others began screaming … ‘How do you like what the niggers did to you in Crown Heights?’

“ ‘Now you got a nigger right inside City Hall. How do you like that? A nigger mayor.’

Newsday reported on other instances of racial abuse. City Councilwoman Una Clarke, a petite black woman, was blocked from crossing Broadway “by a beer‐drinking, off‐duty police officer who said to his sidekick: ‘This nigger says she’s a member of the City Council.’ ”

Former NYPD officer and New York state senator Eric Adams, currently serving as Brooklyn’s borough president, told Newsday at the time that the demonstration was “right out of the 1950s: A drunk, racist lynch mob storming City Hall and coming in here to get themselves a nigger.”

An internal‐strategy report (the “Rudolph W. Giuliani Vulnerability Study”) prepared for the candidate’s 1993 mayoral campaign devoted more than 50 pages to the 1992 police riot under the all‐caps heading “RACIST.”

“When dealing with direct questions about the police rally, Giuliani should acknowledge and criticize the underlying racial nature of the protest,” the study urged.

Giuliani never condemned the overt racism of the 1992 NYPD riot. Instead, he ordered the vulnerability study destroyed, but a copy was leaked to journalist Wayne Barrett in 2000.

Giuliani won the 1993 election against Dinkins and won re‐election in 1997. During his two terms, the NYPD ran roughshod over the civil liberties of all New Yorkers, particularly in neighborhoods where most young men of color grew up under the thumb of constant police harassment. At the heart of Giuliani’s law enforcement policy, in case after case, was a lack of accountability for police misconduct. There is nothing that the onetime presidential candidate can tell us about proper policing that is worth listening to.

This isn’t the first time in recent years that Giuliani has rattled the chains of racial division.

In 2014, after a grand jury cleared NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo in the chokehold death of Eric Garner, Giuliani criticized Mayor Bill de Blasio for publicly acknowledging a history of racism within the police department. “This helps to create this atmosphere of protest, and even sometimes violence,” he said on “Fox & Friends.”

Giuliani was particularly critical of de Blasio’s comment that he has had to train his own mixed‐race son on how to avoid being victimized by the police: “I was always told the policeman’s always right. There’s a good reason for that: He’s got a gun.”

The lesson Giuliani should have learned a long time ago is that the police should always be held accountable, not only because they carry a gun in their holster, but because they have been entrusted with the full power of the state to use that gun to end human life.

“Making police accountable is essential,” said former NYPD detective David Durk, who, along with Frank Serpico, broke the blue wall of silence before the Knapp Commission in 1971. “At 3 o’clock in the morning, a cop is more powerful than the mayor, the governor and the president. He can kill you.”