This New COVID Wave May Be More Like a Flood

A new COVID wave now fueled by four Omicron subvariants continues to drive up infections throughout the country. Though there are signs that the surge in the Northeast has begun to stabilize, infections are on the rise in other regions and the level of community transmission remains high across the vast majority of the country. There is also reason to worry that the current wave may not subside for a long time, particularly now that the two newest and most troubling Omicron subvariants, BA.4 and BA.5, may be starting to outcompete their predecessors. While previous nationwide surges in cases have mostly played out as single waves, this new one might be more like a flood. It could plateau, or dip and swell from that higher baseline across the coming weeks or even months.

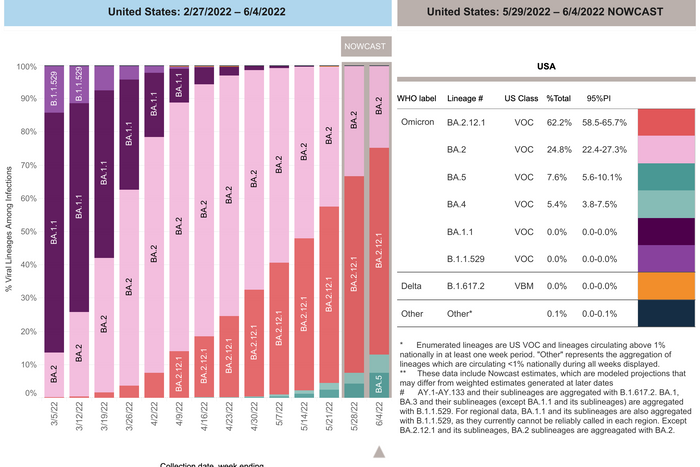

The BA.2.12.1 subvariant, which overtook BA.2 as the nation’s dominant strain last month, still makes up an estimated 62 percent of cases nationwide according to the CDC. BA.4 and BA.5 may be even more transmissible than BA.2.12.1, and it seems clear that they are better equipped to evade immunity induced by prior infection or vaccination. The CDC now estimates that the BA.4 and BA.5 account for a combined 13 percent (5.4 percent BA.4 and 7.6 percent BA.5) of U.S. cases, up from a combined 1.1 percent a month ago.

The sister subvariants, which arrived in the U.S. in March, are on the rise across the country, but especially in some parts of the central U.S. and Southwest. It’s not yet clear whether or not BA.4 and BA.5 will overtake BA.2.12.1 in the U.S. but some COVID experts are predicting it will become dominant in the U.S. and globally, based on some preliminary studies. In recent lab research conducted by scientists at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, BA.4 and BA.5’s unique combination of mutations were found to equip them with a more than 4.2-fold advantage over BA.2 in escaping antibodies in people who have been vaccinated and boosted, whereas BA.2.12.1 only had a 1.8-fold advantage over BA.2 in that regard. The researchers also found that antibodies of vaccinated people who had breakthrough infections offered less protection against BA.4 and BA.5. That suggests, as previous research has, that BA.4 and BA.5 are going to cause a lot of breakthrough infections and reinfections, including among people who caught the original Omicron strain over the winter. That’s what has already happened in South Africa, where BA.4 and BA.5 fueled a wave of cases, despite most of the population having already had Omicron.

The ability of BA.4 and BA.5 to outcompete BA.2.12.1 will become clear very soon, now that they are starting to get a foothold in places like New York where the spread of BA.2.12.1 has been rampant. CNN additionally reports that data out of the U.K. found that the sister subvariants were spreading faster there than BA.2.12.1 was. “The betting favorite now suggests that BA.4 and BA.5 would be able to take out BA.2.12.1,” the assistant director of the University of Washington’s clinical virology laboratory, Dr. Alex Greninger, told CNN, adding that, “For the summer, going into the winter, I expect these viruses to be out there at relatively high levels.”

The good news across the board with all of the Omicron subvariants in the U.S. is that there is not yet evidence that any of these strains cause more severe illness than Omicron does. U.S. COVID hospitalizations have been trending up since the middle of April, including a 16 percent nationwide increase over the last two weeks, but the climb hasn’t been as steep as during previous waves. And while there has always been a lag time between hospitalizations and deaths, thus far COVID deaths haven’t trended up much at all. During the BA.4/5 wave in South Africa, hospitalizations rose but remained low compared with previous waves, and there wasn’t a substantial increase in the number of deaths from COVID there. Scientists have attributed those trends to the very high immunity levels among the population. In other words, while immunity from prior infection or vaccination may not protect well at all against catching BA.4 and BA.5, they may still protect very well against severe illness, particularly among people who have been vaccinated and boosted, or who have hybrid immunity from both vaccination and prior infection.

Still, though the U.S. may see nothing like the spike in hospitalizations and deaths the Omicron wave produced, the country could remain inundated with COVID infections for the foreseeable future — a sustained-spread summer, or as The Atlantic’s Yasmin Tayag has framed it: the “When will it end?” wave. And the level of infections may not drop off before what the Biden administration and many scientists have warned will be a large spike this coming fall or winter.

The other issue is that nobody really knows how many infections this wave is producing — and that will likely remain unclear, both for this and future waves. The wave is undoubtedly much larger than confirmed case counts indicate, since they don’t include all the unreported infections detected by now-ubiquitous at-home COVID tests. Hospitalization rates, COVID levels in wastewater, and test-positivity rates are now a better indicator of wave size than confirmed-case tallies, but each metric has its flaws and they don’t offer a complete picture.

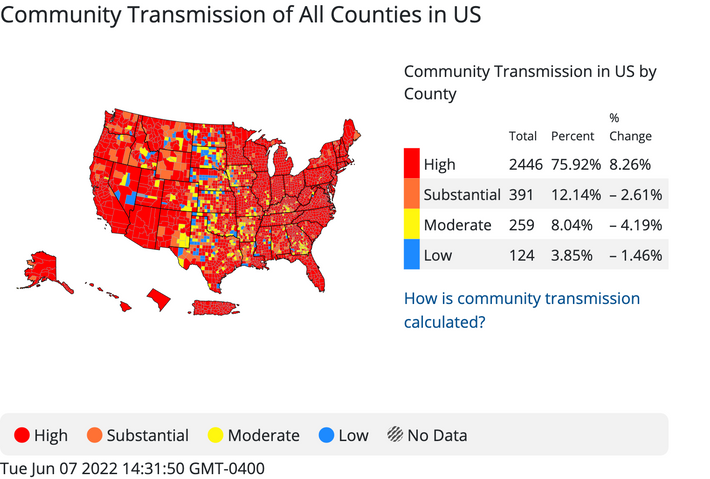

According to the CDC’s community-transmission dashboard, which factors in both reported cases and test-positivity rates, more than 78 percent of U.S. counties are currently experiencing high community transmission of COVID, and nearly 11 percent are experiencing substantial levels of transmission. Some COVID experts have recently speculated that the number of new infections were between five to ten times higher than official case counts indicated. The real number could be even higher than that, according to a new (preprint) study from researchers at the CUNY Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health.

Focusing on the recent surge of infections in New York City, the researchers estimated that more than one in five adult New Yorkers — about 1.5 million people — likely had COVID at some point during the two weeks ending May 8. “It would appear official case counts are under-estimating the true burden of infection by about 30-fold, which is a huge surprise,” one of the study authors, CUNY ISPH epidemiology professor Denis Nash, explained to The Guardian. Furthermore, Nash added, the undercount may be even worse in other places without the relatively high access to testing that New Yorkers have. As he and the study’s other authors warn, the bottom line is that routine COVID surveillance, in its present form, isn’t up to the task of measuring the scope and scale of COVID surges, which denies scientists, politicians, and the public the accurate data needed to make informed decisions about risk and response. (Another alarming estimate from the study was that nearly 56 percent of the New Yorkers who had COVID were not even aware of the antiviral Paxlovid, and only 15 percent said they had received it, indicating a troubling lack of information about, and effective access to, one of the most powerful post-infection weapons we currently have against severe COVID-19.)

America isn’t flying totally blind through this wave, but leaders, public-health officials, scientists, and of course, the public, are stuck with an obstructed view. Even armed with more complete, timely information, it’s far from clear how fast or effectively local, state, and federal leaders would respond. And that’s assuming they are willing to respond much at all; it’s an election year, pandemic interventions are perceived to be politically toxic, and many Americans, now left to manage their individual COVID risk on their own, have dropped their guard and/or diverted their attention to other concerns.

Again, America may avoid the worst outcomes during this wave, namely overwhelming numbers of hospitalizations or a large spike in the number of COVID deaths — but nothing about this wave is good, either. Subvariants that appear to have the most immune escape yet seen during the pandemic are taking hold in a country where waning immunity was already undoubtedly a big problem. The expiration date of Americans’ immunity is still a mystery, as is what will happen after. U.S. booster uptake is among the worst in the developed world, including among seniors, who during Omicron and after have once again become the U.S. demographic disproportionally attacked and killed by COVID. How the wave plays out among the many Americans who remain unvaccinated who have survived previous infections remains to be seen, and the risk of reinfection, overall, also remains unclear. We don’t know if reinfections increase the risk of long COVID, either. And every infection, every reinfection, is another opportunity for the coronavirus to evolve more tricks up its sleeve. BA.4 and BA.5 might not wallop the U.S., but don’t bet on a similar or better outcome from BA.6 or whatever else comes next.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/FCAC2EPKC5A4TBA6FI2WIDPYCY.jpg)