|

How Democracies Die' Authors Say Trump Is A Symptom Of 'Deeper Problems'

FRESH AIR

Harvard professors Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt are experts in what makes democracies healthy — and what leads to their collapse. They warn that American democracy is in trouble. In a new book, they argue that Trump has shown authoritarian tendencies and that many players in American politics are discarding long-held norms that have kept our political rivalries in balance and prevented the kind of bitter conflict that can lead to a repressive state. Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt are both professors of government at Harvard University. Levitsky's research focuses on Latin America and the developing world. Ziblatt studies Europe from the 19th century to the present.

|

| Steven Levitsky (left) and Daniel Ziblatt, |

STEVEN LEVITSKY: ...military coups, although they occur occasionally today in the world, are much, much less common than they used to be. And, in fact, the primary way in which democracies have died since the end of the Cold War, over the last 30 years or so, is at the hands of elected leaders, at the hands of governments that were often freely or close to freely elected, who then use democratic institutions to weaken or destroy democracy. And we're very hopeful that America's democratic institutions will survive this process. But if we were to fall into some kind of crisis, surely it would take that form.

DAVIES: And it doesn't typically happen the week or month after the elected leader takes power, right? It unfolds gradually.

DANIEL ZIBLATT: Yeah, that's right. I mean, that's one of the things that makes it so difficult, both to study and also as a citizen to recognize what's happening. You know, military coups happen overnight. I mean, they're sudden instances - sudden events. Electoral authoritarians come to power democratically. They often have democratic legitimacy as a result of being elected. And there's a kind of gradual chipping away at democratic institutions, kind of tilting of the playing field to the advantage of the incumbent, so it becomes harder and harder to dislodge the incumbent through democratic means.

And, you know, when this goes through the whole process, you know, at the end of the process - this may take years, it may take a decade. You know, in some countries around the world, this has taken as long as a decade to happen. At the end of that process, the incumbent is firmly entrenched in power.

ZIBLATT: Yeah, so at the end of this process, it's hard - it becomes harder and harder - it takes different forms in different countries. I mean, so what's happened in Turkey over the last 10 years, essentially President Erdogan has entrenched himself in power, weakened the opposition, and so it's become harder and harder to dislodge him. So there may continue to be elections, but the elections are tilted in favor of the incumbent. The elections are no longer fair.

Through a variety of mechanisms, the president's able to stay in power and to withstand criticism, although public support may not fully be there. Media is - you know, there's kind of a clampdown on media and sort of a variety of institutional mechanisms that an incumbent can use to kind of keep himself in power.

LEVISKY: Right. As Daniel said, very often these days, the kind of formal or constitutional architecture of democracy remains in place, but the actual substance of it is eviscerated.

|

----

DAVIES: You have a chapter called "Fateful Alliances," and it's about circumstances - cases where a populist demagogue, who turns out to be an authoritarian, got help along the way from mainstream political figures or political parties. Do you want to give us an example of that?

Hitler came to power in a similar alliance with mainstream conservative politicians at the end of the 1920s and into the 1930s - was famously placed as chancellor of Germany by leading statesmen in Germany. In each instance, there's a kind of Faustian bargain that's being struck where the statesmen think that they're going to tap into this popular appeal of the demagogue and think that they can control them. I mean, this is this incredible miscalculation. And this miscalculation happens over and over. And in each instance, the establishment statesmen are not able to control the demagogue.

DAVIES: And you note that there have been figures in American political history that could be regarded as dangerous demagogues and that they've been kept out of major positions of power because we've had gatekeepers - people who somehow controlled who got access to the top positions of power - presidential nominations, for example. You want to give us some examples of this?

LEVISKY: Sure. Henry Ford was an extremist, somebody who was actually written about favorably in "Mein Kampf." He flirted with a presidential bid in 1923, thinking about the 1924 race, and had a lot of support, particularly in the Midwest....George Wallace in 1968, and again in 1972 before he was shot, had levels of public support and public approval that are not different - not much different from Donald Trump. So throughout the 20th century, we've had a number of figures who had 35, 38, 40 percent public support, who were demagogues, who didn't have a strong commitment to democratic institutions, in some cases were quite antidemocratic, but who were kept out of mainstream politics by the parties themselves.

DAVIES: You have a chapter called "Fateful Alliances," and it's about circumstances - cases where a populist demagogue, who turns out to be an authoritarian, got help along the way from mainstream political figures or political parties. Do you want to give us an example of that?

Hitler came to power in a similar alliance with mainstream conservative politicians at the end of the 1920s and into the 1930s - was famously placed as chancellor of Germany by leading statesmen in Germany. In each instance, there's a kind of Faustian bargain that's being struck where the statesmen think that they're going to tap into this popular appeal of the demagogue and think that they can control them. I mean, this is this incredible miscalculation. And this miscalculation happens over and over. And in each instance, the establishment statesmen are not able to control the demagogue.

DAVIES: And you note that there have been figures in American political history that could be regarded as dangerous demagogues and that they've been kept out of major positions of power because we've had gatekeepers - people who somehow controlled who got access to the top positions of power - presidential nominations, for example. You want to give us some examples of this?

LEVISKY: Sure. Henry Ford was an extremist, somebody who was actually written about favorably in "Mein Kampf." He flirted with a presidential bid in 1923, thinking about the 1924 race, and had a lot of support, particularly in the Midwest....George Wallace in 1968, and again in 1972 before he was shot, had levels of public support and public approval that are not different - not much different from Donald Trump. So throughout the 20th century, we've had a number of figures who had 35, 38, 40 percent public support, who were demagogues, who didn't have a strong commitment to democratic institutions, in some cases were quite antidemocratic, but who were kept out of mainstream politics by the parties themselves.

|

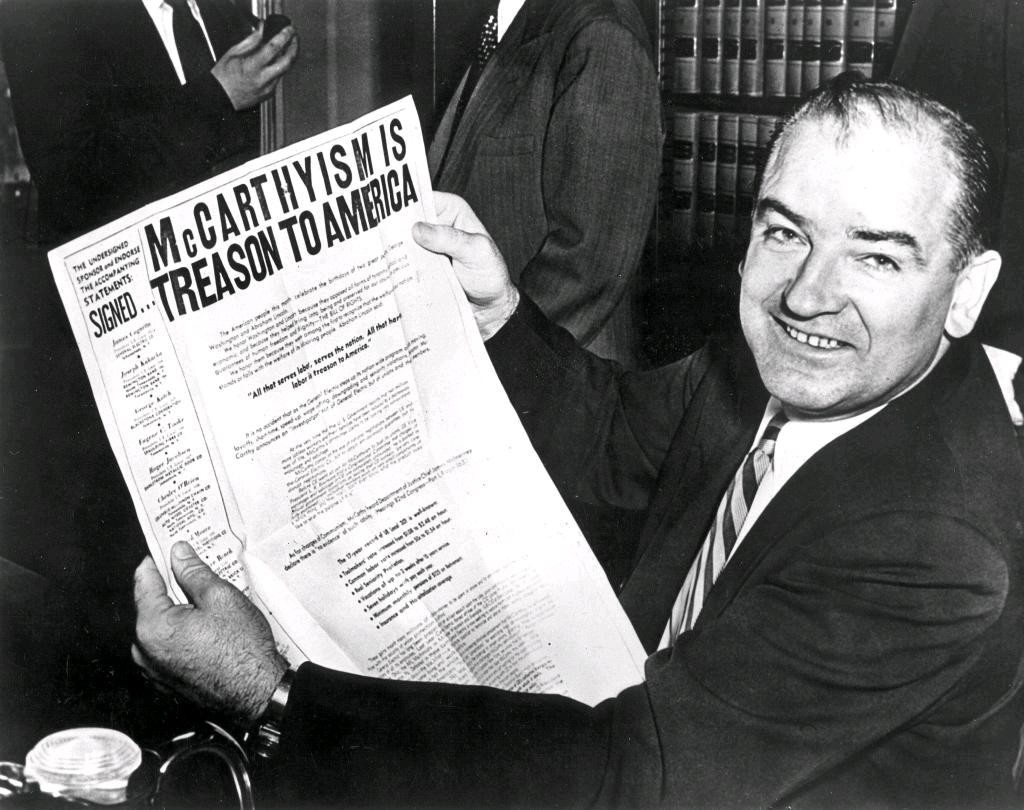

| Sen. Joseph McCarthy, R-Wisconsin |

The parties never even came close to nominating any of these figures for president. What was different about 2016 was not that Trump was new or that he would get a lot of support but that he was nominated by major party. That's what was new.

DAVIES: Right. And you say that there were effectively, for most of American history, gatekeepers at the top of the political party - a process that tended to exclude these people that were more extreme. Describe what that process was like.

ZIBLATT: Yeah, so you know, through the 20th century, even going back to the 19th century, the way presidential candidates were selected has - this has changed over time. And really, only beginning in 1972 have primaries, which we now are all so accustomed to - where candidates are selected by voters - that's when that began is 1972 to be a really significant system. Before 1972, the system throughout the 20th century has often been described as dominated by smoke-filled back rooms where party leaders got together and tried to figure out who would be the best candidate to represent the party and who they thought could win.

You know, there's a lot to be criticized about this pre-1972 system. It was very exclusive. It, you know - it's often picked mediocre candidates. I mean, you can think of President Warren G. Harding, who looked like a presidential candidate but wasn't much of a president. This was somebody who was selected through the smoke-filled backroom. But the virtue of this system - if there is a virtue of it - is that it kept out demagogues.

DAVIES: So in - starting in 1972, there are multiple primaries in states that lead to the party's nomination. There are different state rules. But voters get some say in a lot of it. And you're right that there - but there was always sort of the invisible primary. That is to say you tended to be taken seriously if the party leaders gave you their nod or at least their approval to get in the game. So take us to Donald Trump in 2016. How did this pave the way for Trump?

LEVISKY: Well, the belief among political scientists - and I think it was true for a while - was that winning primaries was hard. This was particularly before the days of social media, when you needed the support of local activists. You needed the support, maybe, of unions in the Democratic Party. You needed the support of local media on the ground in each state in order to actually win primaries. You couldn't just get on CNN and expect to win a primary somewhere in the West because of what you - or what you tweeted.

You had to have some kind of an infrastructure on the ground. I'm talking about the 1970s, 1980s, even the 1990s. And so the belief among political scientists was you still needed the support of party insiders to win the primaries, to win - to cross the country and accumulate enough delegates, winning state by state by state. You really needed to build alliances with local Democratic or Republican Party leaders, committees, senators, congresspeople, mayors, et cetera.

That became less and less true over time in large part because the nature of media - the rise of social media and the ability of outsiders to make a name for themselves without going through that process, without going through that invisible primary. So Donald Trump demonstrated, you know, beyond any doubt in 2016 that at least if you have enough name recognition, you can avoid building alliances with anybody, really, at the state or local level. You can run on your own. You can be an outsider and win.

ZIBLATT: Yeah. I would add to that what's an interesting - differences exist between the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. The Democratic Party has superdelegates. And so there is built into the Democratic Party presidential selection process - continues to exist - this kind of element of gatekeeping. The Republican Party does not have superdelegates. And so one of the interesting kind of things to think about is, you know, had there been superdelegates in the Republican Party, would have Donald Trump actually won the nomination?

Would've he run? Would've he won? And so, you know, I think that's kind of an interesting thing to think about. And, you know, superdelegates are now up for debate within the Democratic Party after the Bernie Sanders-Hillary showdown. And so there's a lot of people who think superdelegates should be eliminated so that - this is kind of an ongoing issue of debate.

DAVIES: Right. And superdelegates are - they're typically elected officials or very prominent leaders or fundraisers in the party. But in the Democratic Party, there are - what? - like, 15 percent of the total delegates of the convention - something like that.

LEVISKY: Right. It's about 15 percent.

| George Wallace |

---

A very simple, short Constitution like that of the United States, can never get a - can never fully guide behavior. And so our behavior needs to be guided by informal rules, by norms. And we focus on two of them in particular - what we call mutual toleration, which is really, really fundamental in any democracy, which is simply that among the major parties, there's an acceptance that their rivals are legitimate, that we may disagree with the other side. We may really dislike the other side. But at the end of the day, we recognize publicly - and we tell this to our followers - that the other side is equally patriotic, and that it can govern legitimately. That's one.

The other one is what we call forbearance, which is restraint in the exercise of power. And that's a little bit counterintuitive. We don't usually think about forbearance in politics, but it's absolutely central. Think about what the president can do under the Constitution. The president can pardon anybody he wants at any time. The president can pack the Supreme Court. If the president has a majority in Congress - which many presidents do - and the president doesn't like the makeup of the Supreme Court, he could pass a law expanding the court to 11 or 13 and fill with allies - again, he needs a legislative majority - but can do it. FDR tried.

The president can, in many respects, rule by decree. If Congress is blocking his agenda, he can use a series of proclamations or executive orders to make policy at the margins of Congress. What it takes for those institutions to work properly is restraint on the part of politicians. Politicians have to underutilize their power. And most of our politicians - most of our leaders have done exactly that. That's not written down in the Constitution.

DAVIES: You know, it's interesting. I think one of the things that people say when people warn that Donald Trump or someone else could undermine American democracy and lead us to an authoritarian state is we're different from other countries in the strength of our commitment to democratic institutions. And I'm interested to what extent you think that's true.

ZIBLATT: Yeah. Well, so, you know, there's certainly this notion of an American creed where Americans have a long-standing commitment to principles of freedom and equality. And I think that's very real. And American democracy's older than any democracy in the world. The constitutional regime has been in place for hundreds of years. And this is - should be a source of some solace to us, that democracy's a - the older a democracy is, lots of political science research shows, the less likely it is to break down. And one of the reasons is a commitment of citizens to democratic norms. One thing, though, that kind of gives us kind of pause, and I think that, you know, there is a sub-current - and Steve mentioned this earlier - there is a sub-current in American political culture, and just even in the 20th century, you know, beginning with Henry Ford, you know...Joe McCarthy, you know, all the way - George Wallace - all the way through Trump, there's a sub-current around 30 - you know, Gallup polls going back to the 1930s - around 30 percent of the electorate supporting candidates who often seem to have a questionable commitment to democratic norms.

LEVISKY: The creed to which Daniel refers and the initial establishment of strong democratic norms in this country was founded in a homogeneous society, a racially and culturally homogeneous society. It was founded in an era of racial exclusion. And the challenge is that we have now become a much more ethnically, culturally diverse society, taken major steps towards racial equality, and the challenge is making those norms stick in this new context.

DAVIES: And you do note in the book that the resolution of the conflicts around the Civil War and a restoration of kind of normal democratic institutions was accompanied by denial of voting rights and basic citizenship privileges to African-Americans in the South.

ZIBLATT: Yeah, so this is this great paradox - tragic paradox, really - that we recount in the book, which is that the consolidation of these norms, which we think are so important to democratic life of mutual toleration and forbearance, were re-established, really, at the price of racial exclusion. I mean, there was a way in which the end of Reconstruction - when Reconstruction was a great democratic effort and experiment - and it was a moment of democratic breakthrough for the United States where voting rights were extended to African-Americans. At the end of Reconstruction throughout the U.S. South, states implemented a variety of reforms to reduce the right to vote - essentially, to eliminate the right to vote for African-Americans. And so after the 1870s, American democracy was by no means actually really a full democracy. And we really think that American democracy came - really, it was a consolidated democracy really only after 1965.... it's clear that with the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act, that's at the point at which American democracy became fully consolidated.

|

| Newt Gingrich |

----

You know, you write that the erosion of these norms of democracy, these unwritten rules, which provide - the guardrails of democracy, in a way, that kind of protects us and keeps us on track - that they began to erode well before Donald Trump became president or was a candidate. When did it start?

LEVISKY: It's difficult to find a precise date. But we look at the 1990s and, particularly, the rise of the Gingrich Republicans. Newt Gingrich really advocated and taught his fellow Republicans how to use language that begins to sort of call into question mutual toleration, using language like betrayal and sick and pathetic and antifamily and anti-American to describe their rivals.

And Gingrich also introduced an era or helped introduce - it was not just Newt Gingrich - an era of unprecedented, at least during that period in the century, hardball politics. So you saw a couple of major government shutdowns for the first time in the 1990s and, of course, the partisan impeachment of Bill Clinton, which was one of the first major acts - I mean, that is not forbearance. That is the failure to use restraint.

AVIES: And did Democrats react in ways that accelerated the erosion of the norms?

LEVISKY: Sure. In Congress, there was a sort of tit-for-tat escalation in which, you know, one party begins to employ the filibuster. For decades, the filibuster was a very, very little-used tool. It was almost never used. It was used, on average, one or two times per Congressional session, per Congressional period - two-year period - so once a year. And then it gradually increased in the '70s, '80s, '90s.

It was both parties. So one party starts to play by new rules, and the other party response. So it's a spiraling effect, an escalation in which each party became more and more obstructionist in Congress. Each party did - took additional steps either to block legislation, because it could, or to block appointments, particularly judicial appointments. You know, Harry Reid and the Democrats played a role in this in George W. Bush's presidency - really sort of stepped up obstructionism.

DAVIES: Did the executive orders that President Obama issued when the Republican Congress clearly was not going to cooperate with his agenda - do you think that that was, you know, a violation of the norm of forbearance?

ZIBLATT: Yeah, so this is exactly a part of the same process that Steve just described. So there's this kind of spiral, you know, which is really ominous, where one side plays hardball by holding up nominations, holding up legislation in Congress, and there's a kind of stalemate. And so the other side feels justified in using executive orders and presidential memos and so on. These also are - you know, have been utilized by Barack Obama. So there's a way in which politicians, on both sides, are confronted with a real dilemma, which is, you know, if one side seems to be breaking the rules, and so why shouldn't we? If we don't, we're kind of being the sucker here.

DAVIES: You know, you do seem to say that the Republican Party led the way and was more willing to violate these norms of democracy. Is that the case? And is there something about the Republican Party that makes it different in this respect?

LEVISKY: Yeah, we do think that's true. We think that the most egregious sort of pushing of the envelope began with Republicans, particularly in the 1990s and that the most egregious acts of hardball have taken place at the hands of Republicans. I'll just list four - the partisan impeachment of Bill Clinton, the 2003 mid-district redistricting in Texas, which was pushed by Tom DeLay, the denial - essentially, the theft of a Supreme Court seat with the refusal to even take up the nomination of Merrick Garland in 2016 and the so-called legislative coup pulled off by the Republican-controlled legislature in North Carolina in 2016. Those are among the most egregious acts of constitutional hardball that we see in the last generation, and they're all carried out by Republicans.

Yes, we believe the Republicans have become a more extremist party. For us, the most persuasive explanation has to do with the way our parties have been polarized along racial and cultural lines. And the way that our parties have lined up, with the Democrats being a party, essentially, of secular, educated whites and a diversity of ethnic minorities and the Republicans being a fairly homogeneous white, Protestant party, or white Christian party, the Republicans have basically come to represent a former ethnic majority in decline. You have many - certainly not all - but many Republican voters who feel like the country that they grew up with, or grew up in, is being taken away from them. And that can lead to pretty extremist views and voting patterns.

----

So let's talk about Donald Trump as president. To what extent do you believe he has violated the norms that protect and preserve American democracy?

LEVISKY: Well, he has clearly violated norms. If there's one thing that Donald Trump does with consistency in politics, it's violate norms. But I should say, I mean, he has not violated Democratic rules much. I mean, our democracy remains intact. Donald Trump is very much - is a pretty authoritarian figure. But we've got real democratic institutions, and the rule of law has largely worked. The judicial system has largely worked. The media has been pretty effective. And so Trump hasn't been able to - has not crossed very many lines in terms of actual authoritarianism.

He's clearly violated norms. I think he's accelerated the process of norm erosion that we've just been talking about - that Daniel was talking about. And that's almost certainly going to be consequential in the future. But thus far, luckily, our system's been strong enough to prevent him from breaking any democratic rules.

DAVIES: But clearly, you argue that his, you know, his attempts to demonize the media and undermine its credibility to, you know, treat his opponents of all stripe as sort of not legitimate represents dangerous trends in democracy. Where do you think we're headed?

ZIBLATT: Yeah, so there's two real things that Donald - President Trump has done that make us worry. One is his politicization of the rule of law or of law enforcement intelligence. And so you know, we - in a democracy, law enforcement intelligence have to be neutral. And what he has tried to do with the FBI, with the attorney general's office is to try to turn law enforcement into a kind of shield to protect him and a weapon to go after his opponents. And this is something that authoritarians always do. They try to transform neutral institutions into their favor. And you know, he's had some success of it. There's been lots of resistance as well, though, from - you know, from Congress and from society and media reporting on this and so on. But this is one worrying thing.

A second worrying thing is - that you just described as well is his effort to - his continued effort to delegitimize media and the election process. So he - so one of the things that we worried about a lot in the book was the setting up - and we describe how - the process by which this happened - the setting-up of electoral commission to investigate election fraud.

And so it's - you know, the idea - he set this commission up to investigate a problem that really all evidence suggests does not exist. I mean, there's been this myth of election fraud in the United States for the last 15 years that's been pushed by all sorts of different groups. And he has taken the - he took on this mantle and set up this Federal Election Commission to try to collect evidence of election fraud, you know, voter ID fraud and so on. And really, again, no social scientific evidence supports that this is happening at all.

And many worried that this was really an effort to target voters, to disenfranchise voters who would be voting against Donald Trump and voting against Republicans. And so he kind of joined forces with people who've been working on this already. The stated goal was to clean up elections, which sounds like a wonderful thing. But the actual goal was to disenfranchise voters who would vote against Republicans.

So it turns out now in the last several months, this commission's been disbanded because of the - one of the major factors that led to the - to elimination of this election commission was that the states refused to cooperate. So here's where we see American federalism in action, and I think the checks and balances have worked well. And this has been now transferred over to the Department of Homeland Security. And so you know, in general, this is I think a good news stories. But we don't know what's going to happen next, and this continues to be a major risk, I think.

LEVISKY: We often get the response to our book that, well, you know, Donald Trump has been much more bluster than action. He's mostly been talk. But in practice, he hasn't done very much. And to a degree, that is true. But there are a lot of consequences to his talk and his words. And let me just point to two - the undermining of the credibility of our electoral process and of the free press, right? There are two - it's hard to think of two institutions that are more core, more fundamental to democracy than our elections and our free press.

And what Donald Trump has done by over and over again saying that - lying, saying that our elections are fraudulent, that the election was fraudulent, that 11 million illegal immigrants voted, that the election was not truly fair, free and fair is to convince a very large number of voters, a very large number of Republicans that our elections actually are fraudulent - and the same thing with the media.

He has convinced a fairly large segment of our society that the mainstream media - that the establishment media is conspiring to bring his government down, is purposefully lying and making stuff up such that a fairly large number of Americans no longer believe anything but Fox News. In the long term, it's hard to imagine how that's healthy for a democracy.

You know, you write that the erosion of these norms of democracy, these unwritten rules, which provide - the guardrails of democracy, in a way, that kind of protects us and keeps us on track - that they began to erode well before Donald Trump became president or was a candidate. When did it start?

LEVISKY: It's difficult to find a precise date. But we look at the 1990s and, particularly, the rise of the Gingrich Republicans. Newt Gingrich really advocated and taught his fellow Republicans how to use language that begins to sort of call into question mutual toleration, using language like betrayal and sick and pathetic and antifamily and anti-American to describe their rivals.

And Gingrich also introduced an era or helped introduce - it was not just Newt Gingrich - an era of unprecedented, at least during that period in the century, hardball politics. So you saw a couple of major government shutdowns for the first time in the 1990s and, of course, the partisan impeachment of Bill Clinton, which was one of the first major acts - I mean, that is not forbearance. That is the failure to use restraint.

AVIES: And did Democrats react in ways that accelerated the erosion of the norms?

LEVISKY: Sure. In Congress, there was a sort of tit-for-tat escalation in which, you know, one party begins to employ the filibuster. For decades, the filibuster was a very, very little-used tool. It was almost never used. It was used, on average, one or two times per Congressional session, per Congressional period - two-year period - so once a year. And then it gradually increased in the '70s, '80s, '90s.

It was both parties. So one party starts to play by new rules, and the other party response. So it's a spiraling effect, an escalation in which each party became more and more obstructionist in Congress. Each party did - took additional steps either to block legislation, because it could, or to block appointments, particularly judicial appointments. You know, Harry Reid and the Democrats played a role in this in George W. Bush's presidency - really sort of stepped up obstructionism.

DAVIES: Did the executive orders that President Obama issued when the Republican Congress clearly was not going to cooperate with his agenda - do you think that that was, you know, a violation of the norm of forbearance?

ZIBLATT: Yeah, so this is exactly a part of the same process that Steve just described. So there's this kind of spiral, you know, which is really ominous, where one side plays hardball by holding up nominations, holding up legislation in Congress, and there's a kind of stalemate. And so the other side feels justified in using executive orders and presidential memos and so on. These also are - you know, have been utilized by Barack Obama. So there's a way in which politicians, on both sides, are confronted with a real dilemma, which is, you know, if one side seems to be breaking the rules, and so why shouldn't we? If we don't, we're kind of being the sucker here.

DAVIES: You know, you do seem to say that the Republican Party led the way and was more willing to violate these norms of democracy. Is that the case? And is there something about the Republican Party that makes it different in this respect?

LEVISKY: Yeah, we do think that's true. We think that the most egregious sort of pushing of the envelope began with Republicans, particularly in the 1990s and that the most egregious acts of hardball have taken place at the hands of Republicans. I'll just list four - the partisan impeachment of Bill Clinton, the 2003 mid-district redistricting in Texas, which was pushed by Tom DeLay, the denial - essentially, the theft of a Supreme Court seat with the refusal to even take up the nomination of Merrick Garland in 2016 and the so-called legislative coup pulled off by the Republican-controlled legislature in North Carolina in 2016. Those are among the most egregious acts of constitutional hardball that we see in the last generation, and they're all carried out by Republicans.

Yes, we believe the Republicans have become a more extremist party. For us, the most persuasive explanation has to do with the way our parties have been polarized along racial and cultural lines. And the way that our parties have lined up, with the Democrats being a party, essentially, of secular, educated whites and a diversity of ethnic minorities and the Republicans being a fairly homogeneous white, Protestant party, or white Christian party, the Republicans have basically come to represent a former ethnic majority in decline. You have many - certainly not all - but many Republican voters who feel like the country that they grew up with, or grew up in, is being taken away from them. And that can lead to pretty extremist views and voting patterns.

| Tom deLay |

So let's talk about Donald Trump as president. To what extent do you believe he has violated the norms that protect and preserve American democracy?

LEVISKY: Well, he has clearly violated norms. If there's one thing that Donald Trump does with consistency in politics, it's violate norms. But I should say, I mean, he has not violated Democratic rules much. I mean, our democracy remains intact. Donald Trump is very much - is a pretty authoritarian figure. But we've got real democratic institutions, and the rule of law has largely worked. The judicial system has largely worked. The media has been pretty effective. And so Trump hasn't been able to - has not crossed very many lines in terms of actual authoritarianism.

He's clearly violated norms. I think he's accelerated the process of norm erosion that we've just been talking about - that Daniel was talking about. And that's almost certainly going to be consequential in the future. But thus far, luckily, our system's been strong enough to prevent him from breaking any democratic rules.

DAVIES: But clearly, you argue that his, you know, his attempts to demonize the media and undermine its credibility to, you know, treat his opponents of all stripe as sort of not legitimate represents dangerous trends in democracy. Where do you think we're headed?

ZIBLATT: Yeah, so there's two real things that Donald - President Trump has done that make us worry. One is his politicization of the rule of law or of law enforcement intelligence. And so you know, we - in a democracy, law enforcement intelligence have to be neutral. And what he has tried to do with the FBI, with the attorney general's office is to try to turn law enforcement into a kind of shield to protect him and a weapon to go after his opponents. And this is something that authoritarians always do. They try to transform neutral institutions into their favor. And you know, he's had some success of it. There's been lots of resistance as well, though, from - you know, from Congress and from society and media reporting on this and so on. But this is one worrying thing.

A second worrying thing is - that you just described as well is his effort to - his continued effort to delegitimize media and the election process. So he - so one of the things that we worried about a lot in the book was the setting up - and we describe how - the process by which this happened - the setting-up of electoral commission to investigate election fraud.

And so it's - you know, the idea - he set this commission up to investigate a problem that really all evidence suggests does not exist. I mean, there's been this myth of election fraud in the United States for the last 15 years that's been pushed by all sorts of different groups. And he has taken the - he took on this mantle and set up this Federal Election Commission to try to collect evidence of election fraud, you know, voter ID fraud and so on. And really, again, no social scientific evidence supports that this is happening at all.

And many worried that this was really an effort to target voters, to disenfranchise voters who would be voting against Donald Trump and voting against Republicans. And so he kind of joined forces with people who've been working on this already. The stated goal was to clean up elections, which sounds like a wonderful thing. But the actual goal was to disenfranchise voters who would vote against Republicans.

So it turns out now in the last several months, this commission's been disbanded because of the - one of the major factors that led to the - to elimination of this election commission was that the states refused to cooperate. So here's where we see American federalism in action, and I think the checks and balances have worked well. And this has been now transferred over to the Department of Homeland Security. And so you know, in general, this is I think a good news stories. But we don't know what's going to happen next, and this continues to be a major risk, I think.

LEVISKY: We often get the response to our book that, well, you know, Donald Trump has been much more bluster than action. He's mostly been talk. But in practice, he hasn't done very much. And to a degree, that is true. But there are a lot of consequences to his talk and his words. And let me just point to two - the undermining of the credibility of our electoral process and of the free press, right? There are two - it's hard to think of two institutions that are more core, more fundamental to democracy than our elections and our free press.

And what Donald Trump has done by over and over again saying that - lying, saying that our elections are fraudulent, that the election was fraudulent, that 11 million illegal immigrants voted, that the election was not truly fair, free and fair is to convince a very large number of voters, a very large number of Republicans that our elections actually are fraudulent - and the same thing with the media.

He has convinced a fairly large segment of our society that the mainstream media - that the establishment media is conspiring to bring his government down, is purposefully lying and making stuff up such that a fairly large number of Americans no longer believe anything but Fox News. In the long term, it's hard to imagine how that's healthy for a democracy.