For more than 180 years, racist stereotypes have been used to entertain.

Al Jolson in the 1930 movie "Mammy."

NY TIMES

By Wil Haygood

Feb. 7, 2019

He keeps showing up, like some slightly bemused and maniacal houseguest, usually intending to get a laugh but instead taking America back into a wicked time warp. The man in blackface stands there, frozen. The photo of him starts to ricochet around our race-haunted land. The outcry begins anew.

We find ourselves in this situation again after a photo was circulated last week showing a man in blackface standing next to a man in a Ku Klux Klan robe on the medical school yearbook page of Gov. Ralph Northam of Virginia. At first, Mr. Northam admitted to being in the photo (without disclosing which of the two men he was), but then he backtracked and denied it. He did, though, admit to a different flirtation with blackface, when he dressed as Michael Jackson. On Wednesday, the state’s attorney general, Mark Herring, also a Democrat, acknowledged that he himself had donned blackface while in college. All this as Virginia, like the rest of the country, celebrates Black History Month.

Blackface in America just won’t go away — consistently showing up at stag parties, on frat row, in college musicals and elsewhere.

But the persistence of blackface is unsurprising. It has been a part of American popular culture since what we recognize as popular culture emerged — roughly round 1832, when Thomas Dartmouth Rice, in blackface, performed his song “Jump Jim Crow” to thunderous applause at the Bowery Theatre in New York.

“It started during President Andrew Jackson’s presidency,” said Rhae Lynn Barnes, a professor of American cultural history at Princeton and the author of the forthcoming “Darkology: When the American Dream Wore Blackface.” She added that minstrel shows and blackface performances, both reinforced and popularized the “stereotype of the dimwitted slave who was happy to be in the South.”

For showbusiness impresarios, there was money to be made in perpetuating such stereotypes.

A partial list of people who have appeared in blackface on screen and stage in the 186 years since Rice’s performance on the Bowery includes: Desi Arnaz, Fred Astaire, Dan Aykroyd, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll (from “Amos ‘n’ Andy”), Ethel Barrymore, Milton Berle, Jimmy Cagney, Joan Crawford, Bing Crosby, Billy Crystal, Ted Danson, Marion Davies, Robert Downey Jr., Judy Garland, Alec Guinness, Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, Benny Hill, Bob Hope, Boris Karloff, Buster Keaton, Hedy Lamarr, Janet Leigh, Harold Lloyd, Sophia Loren, Myrna Loy, the Marx Brothers, David Niven, Laurence Olivier, Will Rogers, Mickey Rooney, Frank Sinatra, Grace Slick, Spencer Tracy, Shirley Temple, John Wayne, Mae West, Gene Wilder and the Three Stooges.

Blackface in America just won’t go away — consistently showing up at stag parties, on frat row, in college musicals and elsewhere.

But the persistence of blackface is unsurprising. It has been a part of American popular culture since what we recognize as popular culture emerged — roughly round 1832, when Thomas Dartmouth Rice, in blackface, performed his song “Jump Jim Crow” to thunderous applause at the Bowery Theatre in New York.

“It started during President Andrew Jackson’s presidency,” said Rhae Lynn Barnes, a professor of American cultural history at Princeton and the author of the forthcoming “Darkology: When the American Dream Wore Blackface.” She added that minstrel shows and blackface performances, both reinforced and popularized the “stereotype of the dimwitted slave who was happy to be in the South.”

For showbusiness impresarios, there was money to be made in perpetuating such stereotypes.

A partial list of people who have appeared in blackface on screen and stage in the 186 years since Rice’s performance on the Bowery includes: Desi Arnaz, Fred Astaire, Dan Aykroyd, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll (from “Amos ‘n’ Andy”), Ethel Barrymore, Milton Berle, Jimmy Cagney, Joan Crawford, Bing Crosby, Billy Crystal, Ted Danson, Marion Davies, Robert Downey Jr., Judy Garland, Alec Guinness, Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, Benny Hill, Bob Hope, Boris Karloff, Buster Keaton, Hedy Lamarr, Janet Leigh, Harold Lloyd, Sophia Loren, Myrna Loy, the Marx Brothers, David Niven, Laurence Olivier, Will Rogers, Mickey Rooney, Frank Sinatra, Grace Slick, Spencer Tracy, Shirley Temple, John Wayne, Mae West, Gene Wilder and the Three Stooges.

[Read our critic Wesley Morris’s assessment of Gov. Northam’s situation.]

“Its longevity is because it’s been institutionalized into every aspect of American life,” Dr. Barnes said. “People have perpetuated blackface because we don’t teach minstrel history. If these people had ever been exposed to it in a safe classroom environment, they would know better.”

Judging from not only various records of campus life but also the numerous Instagram accounts of women appearing as “black” personalities — a phenomenon known as “blackfishing” — many do not know better.

The popularity of blackface was at its height in the early 20th century and has waned sharply since the ’50s, but it certainly hasn’t disappeared. Rather, it has taken on different forms, perhaps more palatable to modern audiences.

In 1986, “Soul Man” was a major Hollywood release, featuring C. Thomas Howell in blackface, posing as an African-American to reap the rewards of affirmative action. As recently as the early 2000s, Jimmy Kimmel wore blackface on “The Man Show” while doing an impression of the basketball player Karl Malone. He has never apologized for it, and he’s on television five nights a week. And it wasn’t until 2015 that the Metropolitan Opera of New York stopped using makeup to darken the faces of the singers in the lead role of “Othello.”

In 1986, “Soul Man” was a major Hollywood release, featuring C. Thomas Howell in blackface, posing as an African-American to reap the rewards of affirmative action. As recently as the early 2000s, Jimmy Kimmel wore blackface on “The Man Show” while doing an impression of the basketball player Karl Malone. He has never apologized for it, and he’s on television five nights a week. And it wasn’t until 2015 that the Metropolitan Opera of New York stopped using makeup to darken the faces of the singers in the lead role of “Othello.”

A screenshot of Jimmy Kimmel in blackface on Comedy Central's "The Man Show," which Kimmel co-hosted from 1999 to 2003.

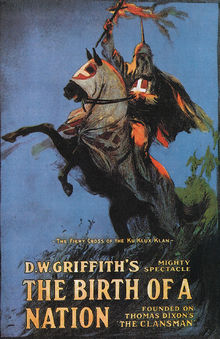

If one were looking for a historical case study in celebrating blackface, well, one could proceed straight to the White House of Woodrow Wilson. Wilson knew Thomas Dixon, a novelist who in 1905 published “The Clansman,” an unabashedly racist book set during Reconstruction, featuring bands of black men looting and raping white women, which became a publishing sensation

The “heroes” of the novel were Ku Klux Klansmen who came to the rescue of the white populace. From the book, the director D.W. Griffith made his lauded and wildly popular film, “The Birth of a Nation.” The major “black” characters in the film were portrayed by white actors in blackface. President Wilson showed the movie at the White House; it may have been the first movie ever screened there. “It is like writing history with lightning,” Wilson was quoted as saying about the film. “And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

The stage adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” provided an additional layer of irony. The book, a runaway success that was often credited as one of the precipitators of the Civil War, told of the horrors of slavery. Theater producers bounded into view. But when the first stage production of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” landed in New York City in 1853, it featured an all-white cast.

As the 19th century wore on, the country swooned over minstrel and vaudeville productions, which often used burnt cork or shoe polish to darken performers’ faces. And over Al Jolson, in particular. It was around 1904 when Jolson, a Jewish man born in what is now Lithuania,began performing in blackface. Broadway beckoned, and in the succeeding years he became the biggest star of both blackface and Broadway. In 1927, he starred in “The Jazz Singer,” the first talking motion picture.

Blackface was such a surefire route to popularity that even black performers started wearing it. Bert Williams, a Bahamian-American comedian, was a major one of these stars, and even in his lifetime his act was freighted with pathos. “Bert Williams was the funniest man I ever saw and the saddest man I ever knew,” W.C. Fields reportedly said.

Sammy Davis Jr., circa 1930.CreditEverett Collection

In perhaps one of the more heartbreaking developments, black child actors were enlisted in blackface acts, including an elementary school-aged Sammy Davis Jr. He was a black child portraying a white man portraying a stereotypical black person. Audiences howled in laughter. It is little wonder that Davis, who died in 1990, would spend a lifetime enduring racial jokes and put-downs, despite his many gifts as an entertainer.

One of the landmark radio shows in American history was “Amos ’n’ Andy,” which began in 1928 and featured white actors portraying black characters. It was rife with black caricature. Black audiences, starved for entertainment, listened as well as whites. In June 1951, the show landed on television. The actors were now black, but the stereotypes were intact. The protests were swift, and the show lasted less than two years.

By then, though, blackface was such an ingrained part of popular American culture — enacted so widely across entertainment media — that it had passed from the stage and screen to everyday life for many.A joke that could be made, a costume that could be worn. And as those recent revelations in Virginia have shown us, it is never long before another door opens and another photo emerges, and there he stands again, the man in blackface.

Wil Haygood, a visiting professor at Miami University (Ohio), has written biographies of Sammy Davis, Jr., Thurgood Marshall and Sugar Ray Robinson. His latest book is “Tigerland: 1968-1969.”

By then, though, blackface was such an ingrained part of popular American culture — enacted so widely across entertainment media — that it had passed from the stage and screen to everyday life for many.A joke that could be made, a costume that could be worn. And as those recent revelations in Virginia have shown us, it is never long before another door opens and another photo emerges, and there he stands again, the man in blackface.

Wil Haygood, a visiting professor at Miami University (Ohio), has written biographies of Sammy Davis, Jr., Thurgood Marshall and Sugar Ray Robinson. His latest book is “Tigerland: 1968-1969.”