/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66120749/GettyImages_672700722.0.jpg)

The controversy over New York’s bail reform law, explained

Cash bail disproportionately affects the poor. So why are Democrats pushing back against a new reform law?

VOX

At the start of the new year, New York joined states like California and New Jersey in taking steps to cease this practice. Criminal courts in the state are now prohibited from setting cash bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies.

Ahead of the law’s passage, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, who proposed his own version of the legislation, praised the move. “The blunt ugly reality is that too often, if you can make bail, you are set free, and if you are too poor to make bail, you are punished,” he said.

But just days after the law took effect, New York media and politicians were in a frenzy. Over the holidays, New York City and surrounding areas had seen a spate of anti-Semitic attacks, and critics of the bail law called for a hate crime exemption to it. Outlets like the New York Post latched onto cases like that of Tiffany Harris, who was arrested three times for assaulting Orthodox Jewish women in Brooklyn in less than a week: “Harris walked free under the state’s new soft-on-crime law,” the Post wrote. On January 10, the New York Daily News ran a cover story of a homeless man who had been charged with assault being released without bail. Staten Island Assembly member Nicole Malliotakis told Tucker Carlson on Fox News that if the law doesn’t get modified, “There’s going to be blood on Governor Cuomo’s hands.”

By January 8, Governor Cuomo had gone on the record saying there were “consequences we have to adjust for,” and that he was open to modifying the law in the next session.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19606287/GettyImages_1190720110.jpg)

But much of the coverage has obscured or downplayed one crucial point: that since 1971, public safety — the idea of the “potential dangerousness” of someone accused of a crime — has not been a legal reason to set bail for a defendant in New York. For nearly 50 years, judges have only been able to consider the defendant’s likelihood of coming to their court date when setting bail, and have been directed to use the “least restrictive” means to get them there. However, just because “potential dangerousness” hasn’t been legally allowed doesn’t mean it hasn’t been the de facto use of bail by judges and prosecutors for decades.

This fear-based messaging has been a favorite tool of opponents of the law. And it’s easy to see how it would catch on in the face of an uptick in hate crimes. But New Yorkers aren’t the only ones concerned about a spike in crime as a result of changing the bail system. Even though violent crime has dropped significantly around the country, some worry that more people charged with crimes “out on the streets” equals a more dangerous society.

In truth, most people in court each day are there for minor offenses. Brooklyn Bail Fund, a nonprofit that has posted bail for more than 4,000 people who could not afford it, reported that those who were released were three times as likely as those who weren’t to have favorable outcomes to their cases. That’s because, defense attorneys say, people who are stuck in jail are much more likely to plead guilty in order to get out, rather than to fight their cases.

In a country overwhelmed by mass incarceration, where about 67 percent of those in county jails are there pretrial, a system where the amount of money you have on hand dictates your freedom seems antiquated at best and unconstitutional at worst.

The New York bail reform law is expected to decrease the number of pretrial detainees by more than 40 percent, according to a report by the nonprofit Center for Court Innovation. But standing in the way of a fairer system are misconceptions held by many Americans about what it is their justice system actually does.

The perception of bail reform versus the reality

Back in the 1960s, New York was in the throes of a similar debate on bail reform. The New York Times ran a series of editorials between 1963 and 1965 arguing the bail system was “a machine to penalize the poor” and advocating for it to be “abolished or drastically modified.” The idea of preventive detention, or detaining someone before their trial for public safety reasons, was hotly debated when the state was passing its first crack at bail reform in 1970. That year, the New York State Legislature passed a law that excluded the “dangerousness” clause and limited a judge’s reasons in setting bail to ensuring that the defendant returns to court.

“Although, legally, bail is not supposed to be used to determine dangerousness, we see that happen all the time,” Khalil Cumberbatch, a formerly incarcerated person who now advocates for reform, told Vox. “Judges just don’t say the term ‘dangerousness.’”

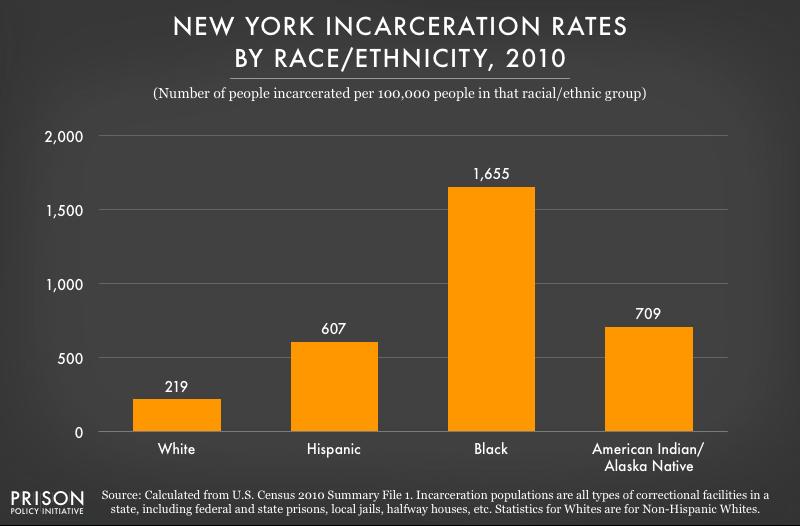

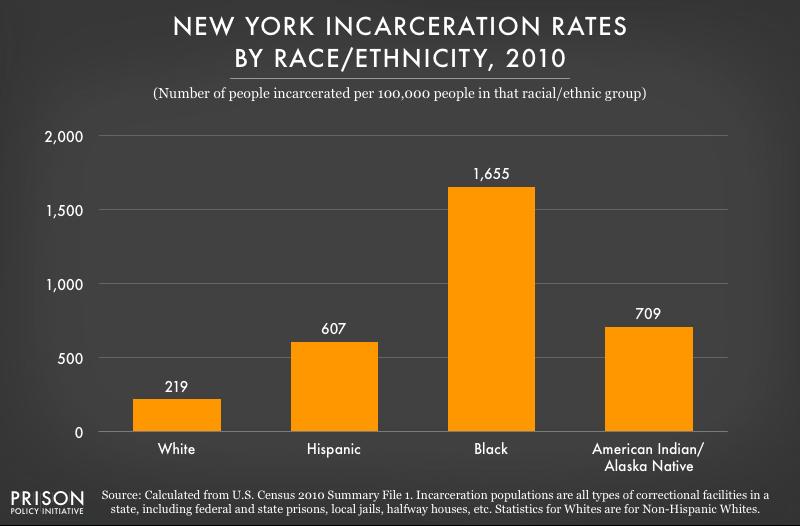

The idea of “dangerousness,” advocates stress, is tied into the racial discrepancies of our justice system. Two studies of state court data from 75 large jurisdictions in the 1990s found that bail was set at significantly higher rates for black and Latinx people.

In the latest bill, signed into law last year and enacted on January 1, judges still can’t consider the potential dangerousness of a defendant. While 90 percent of arrests statewide are now subject to release without bail, violent felonies, sex-related charges, and some domestic violence charges are still subject to cash bail.

“These reforms are a very incremental change — New York State did not get rid of cash bail. It’s still applicable to almost all violent offenses,” Cumberbatch said. “And for someone with means, almost nothing has changed.”

Across America, pretrial detention increased 433 percent from 1970 to 2015, according to a 2019 Vera Institute of Justice report. About two-thirds of people currently in jail have not been convicted of a crime. A 2017 City University of New York report found New York City arrestees who were detained before their trials spent an average of 13-17 days behind bars. But some stay much longer — like Kalief Browder,[photo below] whose tragic story was an inspiration for the law. Because he couldn’t make bail, Browder spent three years at Rikers Island without ever being convicted of a crime, two of those in solitary confinement. Two years after he was released, he died by suicide

.

.

People of color are disproportionately represented in New York’s prisons and jails: More than half of those incarcerated are black, although black people represent just 16 percent of the state’s population. And a 2019 analysis by antipoverty nonprofit FPWA found that “as poverty rates increase, jail incarceration rates increase in New York City community districts.”

In a system where if you can afford to pay bail, you can walk free, even critics of the new law agree that those who are detained are overwhelmingly poor people.

John Flynn, the district attorney in Erie County, which includes Buffalo, said his office has been operating under a policy for the past year and a half in which prosecutors refrain from asking for bail in the majority of misdemeanor cases with a few exceptions, a policy that cut the number of people in jail pretrial by almost 50 percent, he says. “The main reason was the disproportionate economic realities — you have two people charged with the same offense, and one can afford to bond out and one can’t, and that’s just fundamentally unfair,” Flynn said.

But Flynn, who is vice president of the state and national district attorney associations, said the new law goes too far. “My attorneys are no longer able to argue, to point out to a judge, ‘Hey Judge, there’s a good reason to why you should put bail,’” Flynn said. “And the judges, who are elected by the people here in New York State, they now have no discretion at all.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19606304/GettyImages_1195677473.jpg)

Flynn said the law should be amended to include a public safety component similar to the bail reform law passed by New Jersey, which uses an algorithm to predict the likelihood of a defendant to commit further crimes. “Whether or not the person is a danger to himself or another person or society in general — I think a discussion needs to take place on that,” Flynn said.

But proponents of the new law argue that it’s that judicial discretion that resulted in huge numbers of poor people being detained pretrial, and that same discretion also allows for racial bias. The predictive algorithms, too, have come under fire for furthering racial bias. A 2016 ProPublica investigation found that the algorithm in Broward County, Florida, that was used to predict the likelihood of a defendant to commit future crimes “was particularly likely to falsely flag black defendants as future criminals, wrongly labeling them this way at almost twice the rate as white defendants.”

Erin George, the civil rights campaigns director for Citizen Action of New York, said that these conversations about public safety are missing a critical segment of the public. “We have to stop talking about public safety as if the safety of black and brown communities who are targeted by discriminatory pretrial laws and policing, and then forced into the most violent places in the United States, as if their safety doesn’t matter in this conversation,” George said. “Our conversation has to include these people.”

The bail reform movement has produced positive results in nearby New Jersey

What’s happening in New York is part of a larger wave of bail reform sweeping the country. California became the first state to abolish cash bail in 2018 after an appellate court ruled the practice unconstitutional. But after a successful campaign by the bail bonds industry, the law is on hold until California voters take up the issue later this year. Meanwhile, Harris County, home to Houston, has done away with cash bail for misdemeanors after a federal judge ruled the practice unconstitutional, and a similar lawsuit is pending for the felony courts there. Other lawsuits have been filed in states and counties around the country.

New Jersey’s reforms, which happened in 2017, have seen promising results. Not only has there been a 40 percent drop in the number of pretrial detainees, data also shows that since the new law went into effect there was no spike in crime, and people who were released were just about as likely to show up for their court dates.

|

| Gabriela Bhaskar for The New York Times |

This data is heartening for supporters of the New York law, who hope to see similar findings in their state. But Senate Republicans plan to bring a bill to repeal the law in the current legislative session. And with even Democrats, especially in swing districts, calling for some modification of the new law, it’s likely that potential changes to the bill will be heard in the Democrat-controlled House as well