How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future

JILL LEPORE, NEW YORKER

The Simulmatics Corporation opened for business on February 18, 1959, in an office rented by Edward L. Greenfield, the company’s thirty-one-year-old president, on an upper floor of a building at the corner of Madison Avenue and Fifty-second Street, five blocks south of I.B.M.’s glittering World Headquarters. Greenfield, an adman, political consultant, and all-around huckster, pulled people in like a “Looney Tunes” magnet. “Ed Greenfield,” he’d say, flashing a Dean Martin grin, slapping a back, offering a vodka-and-tonic, palming a business card. His new company’s offices were threadbare; his ambition could hardly have been grander. “Simulmatics,” a mashup of “simulation” and “automatic,” had much the same mystique as another nineteen-fifties neologism: “artificial intelligence.”

Decades before Facebook and Google and Cambridge Analytica and every app on your phone, Simulmatics’ founders thought of it all: they had the idea that, if they could collect enough data about enough people and write enough good code, everything, one day, might be predicted—every human mind simulated and then directed by targeted messages as unerring as missiles. For its first mission, Simulmatics aimed to win the White House back for the Democratic Party.

In 1960, John F. Kennedy defeated Richard M. Nixon in a campaign that carries an air of destiny, mainly because of an iconic account by the reporter Theodore H. White.

In “The Making of the President 1960,” White created the myth of Kennedy as an inevitable President—King Arthur, pulling Excalibur from the stone. But Kennedy’s bid for the nomination was a long shot, his victory in the general election was one of the closest in American history, and his campaign deployed an election simulator.

However commonplace now, this was new then, and fiercely controversial. White, while never naming Simulmatics, took the trouble to disavow its influence on the very first page of his book. “It is the nature of politics that men must always act on the basis of uncertain fact,” he wrote. “Were it otherwise, then . . . politics would be an exact science in which our purposes and destiny could be left to great impersonal computers.” White was close to the Kennedy campaign, and the Kennedy campaign had decided to deny, publicly, that it had used Simulmatics.

In 1959, the Democratic Party, at war with itself, was being driven to the grave by segregationists. Republicans had held the White House since Eisenhower’s victory in 1952. Twice, Illinois’s governor, Adlai E. Stevenson, had failed to defeat him.

In 1952, Stevenson had had a segregationist as his running mate, and in 1956 he told a mostly Black audience in Los Angeles that desegregation ought to “proceed gradually.” Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., an African-American congressman from New York, and a Democrat, damned his party for its cowardice, and endorsed Eisenhower.

Even with a new running mate, Stevenson won only states that had been claimed by the Confederacy. Nevertheless, he enjoyed nearly universal support among white liberal intellectuals, including the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., the economist John Kenneth Galbraith, the poet Archibald MacLeish, and The New Yorker’s John Hersey; all four drafted speeches for Stevenson, erudite and elegant. The Eisenhower campaign, meanwhile, ran what Stevenson supporters called a Corn Flakes Campaign: it sold its candidate like laundry detergent. “I think of a man in the voting booth who hesitates between two levers as if he were pausing between competing tubes of toothpaste in a drugstore,” one of his campaign consultants said. “I Like Ike,” the TV jingle ran. “It’s time for a change,” Eisenhower said, in meaningless ad copy written by the guy who came up with M&M’s “Melts in your mouth, not in your hand.”

Ed Greenfield, whose political-consulting firm worked on the Stevenson campaign in 1956, concluded that his speeches were too brainy. “The Emphasis upon Complexity Should Be Minimized,” the company’s social-science division recommended. But Stevenson refused either to simplify or to abandon his quisling position on civil rights. Nixon, Eisenhower’s Vice-President, was a formidable candidate, and a ferocious adversary. To beat him in 1960, Greenfield thought, Democrats needed a secret weapon.

|

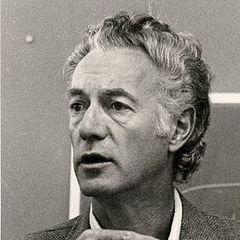

| M.I.T. political scientist Ithiel de Sola Pool, the chairman of Simulmatics’ research board |

Modern American politics began with that secret weapon. Greenfield called it Project Macroscope. He recruited the best and the brightest, many of whom had been trained in the science of psychological warfare. “The scientists are from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Yale, Harvard, Columbia, and Johns Hopkins,” the New York Times reported. Simulmatics’ 1960 election project was one of the largest political-science research projects ever conducted. Led by an M.I.T. political scientist named Ithiel de Sola Pool, the chairman of Simulmatics’ research board, Greenfield’s scientists compiled a set of “massive data” from election returns and public-opinion surveys going back to 1952, sorting voters into four hundred and eighty types, and issues into fifty-two clusters. Then they built what they sometimes called a voting-behavior machine, a computer simulation of the 1960 election, in which they could test scenarios on an endlessly customizable virtual population: you could ask it a question about any move a candidate might make and it would tell you how voters would respond, down to the tiniest segment of the electorate.

“Suppose that during the campaign, the question arises as to the possible consequences of making a strong civil rights speech in the deep South,” Greenfield and Pool wrote:

Should a politician make a strong speech about civil rights in the South because it’s the right thing to do? No. A politician should make a strong speech about civil rights in the South when and where advised to do so by a for-profit data-analytics firm.

After settling into Simulmatics’ new offices, Greenfield sent a proposal for Project Macroscope to Newton Minow, a partner at Stevenson’s Chicago law firm who had served as Stevenson’s counsel. Minow forwarded the proposal to Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., in Cambridge, where he lived two doors down from Ithiel de Sola Pool. “Without prejudicing your judgment, my own opinion is that such a thing (a) cannot work, (b) is immoral, (c) should be declared illegal,” Minow wrote. “Please advise.” Schlesinger looked over the proposal. “I have pretty much your feelings about Project Macroscope,” he wrote back. “I shudder at the implication for public leadership of the notion . . . that a man shouldn’t say something until it is cleared with the machine.” But he wasn’t going to thwart it. “I do believe in science and don’t like to be a party to choking off new ideas.” Project Macroscope went ahead. It’s going on still.

Project Macroscope aimed to solve the problem of Adlai E. Stevenson. Greenfield and Pool, the Columbia sociologist William McPhee, and the Yale psychologist Robert Abelson persuaded the Democratic Advisory Council, a pro-Stevenson arm of the Democratic National Committee, to hire Simulmatics to conduct an initial simulation. It would cost, in 2020 money, nearly six hundred thousand dollars, and it would study the Black vote.

Most Blacks in the South couldn’t vote. And only a tiny slice of Simulmatics’ bank of voters were Black: sixty-five hundred and sixty-four in all, of whom four thousand and fifty were in the North. But the company’s ambition of studying African-Americans as a voting type represented a major change.

George Gallup had notoriously failed to include African-Americans in his surveys, not least because he depended on the financial support of Southern newspapers, which were unwilling to print the opinions of Black Americans, especially about race relations.

At the same time that Simulmatics’ scientists got to work, Kennedy began wooing the liberals who had long supported Stevenson.

In 1958, Kennedy had won reëlection to the Senate with seventy-three per cent of the vote. Still, he had liabilities: he was Catholic, and the United States had never before elected a Catholic President. He was even weaker on civil rights than Stevenson. He was young, only forty-two. He had close ties to Joseph McCarthy: his father had donated money to McCarthy’s crusade; his sister had once dated him; and his brother Bobby had worked for him. And when Congress voted to censure McCarthy, 67–22, Kennedy, in the hospital, chose not to cast a vote. Liberals had never forgiven him. Kennedy set about seeking that forgiveness.

“One morning in mid-July 1959, as I was sitting in the sun at Wellfleet, Kennedy called from Hyannis Port to invite me to dinner that night,” Schlesinger recalled. Visiting the lavish Kennedy compound on Cape Cod, Schlesinger, like White, fell in love with Jackie—“Underneath a veil of lovely inconsequence, she concealed tremendous awareness”—and with Jack, who impressed him with his vigor and determination and intelligence and decisiveness. Quietly, Schlesinger switched sides. For months, he positioned himself as a middleman between Stevenson and Kennedy, passing along messages and setting up meetings, trying to get Stevenson to throw his support behind Kennedy. None of it worked.

On January 2, 1960, Kennedy announced his bid for the Democratic nomination. The Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey had entered the race, too, though he later said, “I felt as competent as any man to be President with the exception of Stevenson.”

In February, at a whites-only lunch counter in a Woolworth’s in Greensboro, four Black students, freshmen from North Carolina A. & T., refused to give up their seats. The sit-ins spread across the South, even as Simulmatics’ scientists wrote code and sorted punch cards, trying to simulate the mind of the Black voter.

On March 8th, Kennedy won the New Hampshire primary. On April 5th, he won in Wisconsin, a painful defeat for the Midwestern Humphrey, who, observing the efficiency of the Kennedy campaign, said, “I felt like an independent merchant competing against a chain store.” The next week, Kennedy won Stevenson’s home state of Illinois. In May, after Kennedy won the West Virginia primary, Humphrey withdrew from the race.

On May 15, 1960, Simulmatics presented its first report, “Negro Voters in Northern Cities,” to the Democratic Advisory Council. In a year when two hundred and sixty-nine of a possible five hundred and thirty-seven Electoral College delegates were needed to win the Presidency, eight states with high African-American voter turnout—New York, Pennsylvania, California, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, New Jersey, and Missouri—would together account for two hundred and ten. African-Americans had long voted Republican, but in the nineteen-thirties F.D.R. had pulled many into his New Deal coalition.

Simulmatics reported that, in the nineteen-fifties, this coalition had begun to fall apart: in 1956 and 1958, Democratic candidates had lost Black voters in the North, especially middle-class Black voters, especially after Eisenhower signed the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

“The shift was not just a swing to ‘Ike,’ ” Simulmatics reported. “It was definitely a shift in party loyalty,” as evidenced by the swing in the 1958 midterms, when Eisenhower was not on the ballot. “The thing that won them over was not the father-image of Eisenhower (who was, however, not disliked) but the image of what each party had done for the Negro people.”

It came to this: the Democratic Party could not win back the White House without winning back those Black voters, and it couldn’t win them back without taking a stronger position on civil rights. Reaching this conclusion might not have seemed to require a team of quantitative behavioral scientists, an I.B.M. 704, and more than half a million dollars—really, you had only to watch the sit-ins on TV. But, given the Party’s intransigence, maybe it did.

By now, Kennedy had all the momentum. Lyndon Johnson, who hated him, orchestrated a “Stop Kennedy” campaign. The New Republic and The Nation endorsed Stevenson, and begged him to run. “Draft Stevenson” groups sprouted up all over the country.

On May 21st, Kennedy visited Stevenson at his house in Libertyville. He asked Stevenson not only to support him but to deliver his nominating speech at the Convention. “Look, I have the votes for the nomination and if you don’t give me your support, I’ll have to shit all over you,” Stevenson recalled being told by Kennedy. “I don’t want to do that but I can, and I will if I have to.” Stevenson refused.

Schlesinger set about trying to knock Stevenson out of the race.

On June 5th, Stevenson visited Cambridge, and stayed at Schlesinger’s house, just over the garden gate from Galbraith’s house. Again, Stevenson refused to endorse Kennedy. Then began a battle of the intellectuals. On June 13th, some of the leading liberals in the United States, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Reinhold Niebuhr, Archibald MacLeish, John Hersey, Carl Sandburg, and John Steinbeck, sent a petition to the Democratic National Committee endorsing Stevenson. Four days later, there appeared a counter-petition, with a list of names headed by Schlesinger and Galbraith. The petition contained Kennedy’s assurance that he supported an end to segregation.

Schlesinger later said that he regretted that the statement had come out so soon after Stevenson had been a guest in his house. Schlesinger’s wife, Marian, told newspapers she was still for Stevenson. (Robert Kennedy wrote in a postscript scrawled at the bottom of a letter to Schlesinger, “Can’t you control your own wife—or are you like me?”) At a party, Galbraith was accused of the “worst personal betrayal in American history.” Not everyone jumped ship.

But Ithiel de Sola Pool did. He sent a copy of Simulmatics’ first, confidential report to a Kennedy aide, Ted Sorensen; Pool may have handed one to Schlesinger, too. Sorensen mulled it over, but, at the moment, he, like everyone else, was busy getting ready for the Democratic National Convention, in Los Angeles. On July 5th, Lyndon Johnson entered the race, mainly to rattle Kennedy. Three days later, on CBS News, Stevenson said that, if drafted, he would run.

Conventions involve a lot of jiggery-pokery and more too-rich food and bad champagne than most people see in a lifetime. Then, there’s the dealmaking. Early in July, the Kennedy campaign set up headquarters in a four-room suite at the Biltmore Hotel. A young writer named Thomas B. Morgan, a very close friend of Ed Greenfield’s (and soon to be Simulmatics’ director of publicity), flew from New York to Los Angeles, where he wore a “Draft Stevenson” button on his lapel. He was there, as press secretary, to help establish headquarters for the nonexistent Stevenson campaign. Kennedy arrived in Los Angeles on Saturday, July 9th. So did Stevenson, who was greeted at the airport by thousands of supporters. Schlesinger, about to board his own plane, wrote in his diary, miserably, “If AES had any chance, I would feel happier in Los Angeles if I were working for him, or at least I think I would; I would feel happier for myself.”

Pool and Greenfield flew to Los Angeles, too, to make sure that Simulmatics’ report on Black voters in the North got into the hands of the platform committee. They had already given a copy of the report to Chester Bowles, the committee chairman, and another to Harris Wofford, a Kennedy staffer and friend of Greenfield’s who would draft the platform’s civil-rights plank. (“Let me suggest that some time soon you try to talk with a good friend of mine, a very astute public relations man, Ed Greenfield,” Wofford had written to Martin Luther King, Jr., earlier that year.) Bowles had appointed a twenty-man drafting panel that included only four Southerners. Meeting on Sunday, July 10th, it endorsed a platform called “The Rights of Man.” Its boldest plank staked out the most liberal position on civil rights ever taken by either party.

The public sees what happens on the Convention floor; the dealmaking takes place behind closed doors. Gore Vidal hosted a party that, as Schlesinger reported, included “everyone from Max Lerner to Gina Lollobrigida.” The morning after a party at the Beverly Hills Hotel, Minow pulled Stevenson into a bathroom, for a private word.

“Governor,” he said, “you can listen to what you hear from those people or to me. Illinois is caucusing in fifteen minutes and it’s almost one hundred percent for Kennedy.”

“Really?” Stevenson asked. “What do you suggest?”

“I suggest you not go out of here a defeated guy trying to get nominated a third time,” Minow said. “I suggest you come out for Kennedy, be identified with his nomination, and unite the party.”

Stevenson dithered. On the morning of Monday, July 11th, in the Kennedy suite at the Biltmore, Bobby Kennedy held a staff meeting. He took off his coat and loosened his tie and climbed onto a chair. “I want to say a few words about civil rights,” he said. “We have the best civil-rights plank the Democratic party has ever had. I want you fellows to make it clear to your delegations that the Kennedy forces are unequivocally in favor of this plank.” Schlesinger found it one of the most impressive speeches of the Convention.

Outside the arena, thousands of Stevenson supporters gathered, chanting and carrying banners. (“a thinking man’s choice—stevenson!” “face the moral challenge—stevenson.”) Even White admitted, “This was more than a demonstration, it was an explosion.” By Tuesday, the number of Stevenson supporters outside the arena seemed to have doubled. That night, Stevenson entered the Convention hall, not as a candidate but as a delegate for Illinois, to seventeen minutes of applause. Wednesday newspapers ran new headlines: “kennedy tide ebbs.”

The Minnesota senator Eugene McCarthy nominated Stevenson. On Wednesday night, McCarthy rose to make his speech. “Do not leave this prophet without honor in his own party,” he pleaded. “Do not reject this man.” By Morgan’s count, the applause lasted for twenty-seven minutes. And there was the unending chant, “We Want Stevenson!” Morgan described “a giant papier-mâché ‘snowball’—made of petitions bearing more than a million signatures calling on the convention to ‘Draft Stevenson’ ” floating up from the rostrum. Someone yelled, “Look, it’s Sputnik!”

As the galleries seemed to surge and throb, the delegates on the floor were strangely silent. McCarthy asked them to set themselves free from whatever pledge they’d made, no matter the caucuses and the primaries. But most delegates considered themselves bound, at least in the first ballot, by their instructions from the voters. “This the delegates knew; but not the galleries,” White wrote. Stevenson, in any case, had already lost. Earlier that day, he’d tried to persuade Chicago’s Mayor Richard Daley to deliver the Illinois delegation to him, and Daley had refused. His campaign ended before it had begun.

Kennedy was persuaded to offer the Vice-Presidency to Lyndon Johnson, as a means of assuring that, as President, he would have the full support of Johnson as Senate Majority Leader. No one expected Johnson to accept. “You just won’t believe it,” Kennedy said, when he came back from meeting with Johnson. “He wants it!”

Finally, on Friday, July 15th, an exhausted Kennedy delivered an acceptance speech so lacklustre that it gave Nixon confidence that he would have no trouble handling Kennedy in a televised debate. Schlesinger watched with a twinge. “I believe him to be a liberal,” he wrote in his diary. “I also believe him to be a devious and, if necessary, a ruthless man.” The next day, seeking out that ruthless man, Pool wrote to the Kennedy-for-President headquarters, formally offering the services of the Simulmatics Corporation.

Minow thought Project Macroscope was unethical and ought to be illegal. Schlesinger thought it just might work. On August 11th, Simulmatics began to compile three reports for the Kennedy campaign. Two weeks later, the firm presented its findings to Bobby Kennedy and top campaign staff, at a briefing held in R.F.K.’s office.

There’s really no way to measure the influence of the Simulmatics reports on the Kennedy campaign. After the briefing, the campaign followed Simulmatics’ advice about what Kennedy should do. The question is whether the Kennedy campaign would have done these things, anyway.

To conventional polls and political analysis, Simulmatics added computer simulations, not unlike, say, the simulations used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to predict the number of new covid-19 cases given various scenarios. A simulation program works by way of endless if/then statements: if this, then that. if/then was the syntax of Simulmatics’ reports. They began with the state of play: Kennedy was behind Nixon in the polls, but nearly a quarter of voters had not yet made a decision. “Negro voters are a danger point for the Kennedy campaign,” the Simulmatics team observed, and Jewish support for Kennedy was fairly weak, suggesting that “a straightforward attack on prejudice will appeal to these minorities since they are ideologically inclined to oppose such prejudices.” What Kennedy viewed as a liability might be turned into a strength. “The issue of anti-Catholicism and religious prejudice could become much more salient in the voters’ minds. If that occurs, what will happen?” The team had run a computer simulation, analyzing the effect of further discussion of religion on each of four hundred and eighty voter types concerning “(1) its past voting record; (2) its turnout at the polls; and (3) its attitude toward a Catholic candidate.”

As a result of this analysis, Simulmatics recommended that Kennedy confront the religious issue, with the aim not of averting criticism but of inciting it: “The simulation shows that Kennedy today has lost the bulk of the votes he would lose if the election campaign were to be embittered by the issue of anti-Catholicism. The net worst has been done.” If Kennedy were to talk more and more openly about his Catholicism, then he would be attacked for it. And, if he were attacked, that would shore up support where he needed it most. Simulmatics made this case on August 25th. Kennedy began tackling the issue of his Catholicism head on in early September.

Instead of deflecting anti-Catholic opposition, the campaign drew attention to it, seeking opportunities for the candidate to respond by decrying religious prejudice. Speaking before Protestant ministers of the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12th, Kennedy squarely condemned religious intolerance. “I may be the victim, but tomorrow it may be you,” he said. And he warned, “I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for President who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters, and the Church does not speak for me.”

Kennedy, who had been trailing Nixon in the polls all summer, gained on him after Labor Day because of his frank talk about religion, because of his new stand on civil rights, and because of his performance in televised debates with Nixon. In each of these cases, the approach he took had been recommended by Simulmatics.

Simulmatics had urged a stronger stance on civil rights in its first report, presented to the D.N.C. in May, sent by Pool to the Kennedy campaign in June, and handed to the chairman of the platform committee by Greenfield in advance of the Convention. Immediately after the Convention, Kennedy, who, according to White, was the Democratic candidate least appealing to African-Americans, set up a civil-rights “division” headed by Harris Wofford, the friend of Ed Greenfield’s who had drafted the civil-rights plank of the Party’s platform.

In October, Kennedy dramatically improved his standing with African-American voters when (urged by Wofford) he called Coretta Scott King, after her husband was arrested at a sit-in in Atlanta. One of the Simulmatics reports given to Kennedy specifically addressed the upcoming debates, describing them as a risk for Nixon: “The danger to Nixon is that Kennedy can make use of his more personable traits—including a range of emotions such as fervor, humor, friendship, and spirituality beyond the expected seriousness and anger.”

Kennedy spent Election Night, November 8th, at his family’s compound in Hyannis Port, where a pink-and-white children’s bedroom on the second floor of Robert Kennedy’s house had been converted into a data-analysis center. All night, Kennedy walked back and forth across the lawn, from his own house, where Jackie, eight months pregnant, was trying to rest, to Bobby’s house, where teletype keys were clattering. But ordinary Americans had their own data-analysis centers in their living rooms, or their kitchens, or wherever they watched television.

The election of 1960 was the fastest-reported one in American history. In Studio 65, CBS News’ election headquarters, an I.B.M. 7090 made a preliminary prediction at 7:26 p.m., when hardly any polls had closed, and with less than one per cent of all precincts reporting. CBS cautiously predicted a victory for Nixon. The mood at the Kennedy compound turned gloomy. But at 8:12 p.m., with four per cent of precincts reporting, the 7090 offered a new prediction: Kennedy would win with fifty-one per cent of the popular vote; two minutes later, CBS broadcast this prediction, absent any caveat.

I.B.M.’s prediction held. Kennedy’s electoral margin of victory, three hundred and three to two hundred and nineteen, was wide. But his margin in the popular vote—49.7 per cent to 49.6 per cent—was the closest since 1888, close enough to lead to two recount efforts led by the Republican National Committee but not endorsed by Nixon, who told a biographer that he wanted to spare the country the “agony of a constitutional crisis.” And, as Simulmatics had predicted, “Negro Voters in Northern Cities” turned out to be crucial to the Democrats’ victory. Kennedy won six of the eight states mentioned in the report.

“What we have demonstrated is how data from past situations can be used to simulate a future situation,” the scientists of Simulmatics had boasted. Were they flimflam men? Or had they reinvented American politics?

Simulmatics launched a publicity blitz. Five days after the election, the Boston Globe ran a piece about how Simulmatics had told Kennedy “why and what he must do” and credited the data company with both his victory in the debates and his position on civil rights. “We know the Kennedy brothers read our reports the day they got them—and knew what was in them three days later,” Pool told the reporter. “They are great readers.”

Simulmatics launched a publicity blitz. Five days after the election, the Boston Globe ran a piece about how Simulmatics had told Kennedy “why and what he must do” and credited the data company with both his victory in the debates and his position on civil rights. “We know the Kennedy brothers read our reports the day they got them—and knew what was in them three days later,” Pool told the reporter. “They are great readers.”

Even before the election, word had got out that White was writing a book about the campaign. Pool decided to write his own book about the making of the President, the story of how a “starry-eyed notion on the frontiers of science became a reality.”

Meanwhile, Morgan pitched an article to Harper’s. His story, “The People Machine,” appeared in the January, 1961, issue, which hit newsstands the week before Christmas and stayed there nearly until Kennedy’s Inauguration.

Most of the Cambridge Analytica-era questions and concerns raised in the early decades of the twenty-first century about computers and politics were first raised by Morgan’s essay in Harper’s, nearly six decades ago: “If, in a free society, information is power, how do we prevent tampering with the data provided by the machine? . . . As we seek more and more data for the machines, can we maintain our traditions of privacy?” The story was picked up all over the country.

The New York Herald Tribune reported that “a big, bulky monster called a ‘Simulmatics’ ” had been Kennedy’s “secret weapon.” An Oregon newspaper editorialized that the Kennedy campaign had reduced “the voters—you, me, Mrs. Jones next door, and Professor Smith at the university— . . . to little holes in punch cards,” implying that the tyranny of the People Machine made “the tyrannies of Hitler, Stalin and their forebears look like the inept fumbling of a village bully.” “Mouth more or less agape and breath more or less bated, we have been reading how by ‘simulmatics’ this marvelous contrivance gave young Mr. Robert Kennedy the ‘advance dope’ on problems as opaque as the religious issue,” the editors of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote dubiously. “Hinkle-pinkle! If Mr. Kennedy took serious stock in the machine—‘a model of the American people’ better than the original since it knew what the people would do even before they were sure—that would be enough to explain how he came so close to losing the election.” The distance between then and now is the measure of how entirely the American voting public now takes this kind of political shenanigan for granted. “Mouth agape” is not how Americans view the ordinary undertakings of the thousands of data-analytics firms that have come to advise our political campaigns.

Directly after that issue of Harper’s hit newsstands, Pierre Salinger, Kennedy’s press secretary, issued a public denial. “We did not use the machine,” Salinger said. “Nor were the machine studies made for us.” The rebuke ran in papers all over the country, under headlines like “kennedy camp denies use of an electronic ‘brain.’ ” But the denial only fanned the flames. “The fact remains,” the editors of the Cincinnati Enquirer remarked, “that the machine knew whereof it spoke.” The conservative columnist Victor Lasky confronted Salinger with the evidence. “Pierre’s recollection was somewhat refreshed,” Lasky later wrote, “after it was disclosed that Bobby Kennedy had helped finance the People Machine . . . and that reports based on its findings went directly to Bobby.” (Simulmatics’ reports can be found, today, in the archives at the Kennedy Library.)

In “J.F.K.: The Man and the Myth,” a fierce and partisan book published in September, 1963, Lasky would all but argue that, by using a computer simulation, Kennedy had stolen the election from Nixon. But after Kennedy was assassinated Lasky’s publishers halted printing. “I’ve cancelled out of everything,” Lasky said after the President’s death. “As far as I am concerned Kennedy is no longer subject to criticism on my part.”

Still, criticism endured. The University of California political theorist Eugene Burdick had worked for Greenfield in 1956, but decided not to join Simulmatics. Instead, he wrote a novel about it. In “The 480,” a political thriller published in 1964, a barely disguised “Simulations Enterprises” meddles with a U.S. Presidential election. “This may or may not result in evil,” Burdick warned. “Certainly it will result in the end of politics as Americans have known it.”

That same year, in “Simulacron-3,” a science-fiction novel set in the year 2034, specialists in the field of “simulectronics” build a People Machine—“a total environment simulator”—only to discover that they themselves don’t exist and are, instead, merely the ethereal, Escherian inventions of yet another People Machine. After that, Simulmatics lived on in fiction and film, an anonymous avatar. In 1973, the German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder adapted “Simulacron-3” into “World on a Wire,” a forerunner of the 1999 film “The Matrix,” in which all of humanity lives in a simulation, trapped, deluded, and dehumanized.

The first array of the matrix was erected in 1959. After the election of 1960, the Simulmatics Corporation ventured into nearly every realm of American life. In 1961, it introduced computer simulation to the advertising industry. In 1962, it was the first data firm to provide real-time computing to an American newspaper—the Times—for the purpose of analyzing election results. In 1963, it simulated the entire economy of a developing nation, Venezuela, with an eye toward thwarting Communist revolution.

Beginning in 1965, Simulmatics conducted psychological research in Vietnam as part of a larger project of waging a war by way of computer-run data analysis and modelling. In 1967 and 1968, at home, Simulmatics attempted to build a race-riot-prediction machine. In 1969, after antiwar demonstrators called Pool a war criminal, the People Machine crashed; in 1970, the company filed for bankruptcy. (Most of its records were destroyed; I stumbled across what remains, in Pool’s papers, at M.I.T.)

Simulmatics is a relic of its time, an artifact of the Eisenhower-Kennedy-Nixon Cold War; a product of the Madison Avenue of M&M’s and toothpaste ads; a casualty of mid-century American liberalism. The Simulations Enterprises of “The 480” is a mega-corporation and the “simulectronics” specialists in “Simulacron-3” are technical geniuses. The real Simulmatics Corporation was a small, struggling company. It was said to be the “A-bomb of the social sciences.” But, like a long-buried mine, it took decades to detonate. The People Machine was hobbled by its time, by the technological limitations of the nineteen-sixties. Data were scarce. Models were weak. Computers were slow. The men who built the machine could not repair it: the company’s behavioral scientists had little business sense, its chief mathematician contended with insanity, its computer scientist fell behind the latest research, its president drank too much, and nearly all their marriages were falling apart. The machine sputtered, sparks flying, smoke rising, and ground to a halt.

Simulmatics failed. And yet it had built a very early version of the machine in which humanity would find itself trapped in the early twenty-first century, a machine that applies the science of psychological warfare to the affairs of ordinary life, a machine that manipulates opinion, exploits attention, commodifies information, divides voters, atomizes communities, alienates individuals, and undermines democracy. Facebook, Palantir, Cambridge Analytica, Amazon, the Internet Research Agency, Google: these are, every one, the children of Simulmatics.

“The Company proposes to engage principally in estimating probable human behavior by the use of computer technology,” Greenfield promised investors in Simulmatics’ initial stock offering. By the time of the 2016 election, the mission of Simulmatics had become the mission of nearly every corporation. Collect data. Write code: if/then/else. Detect patterns. Predict behavior. Direct action. Encourage consumption. Influence elections. If Simulmatics had not begun this work, then it would have been done by someone else. But, if someone else had done it, then it might have been done differently. ♦