How Stephen Miller went from teen troll to Trump whisperer

Jean Guerrero’s new book, ‘Hatemonger,’ details the Trump aide’s early influences -- and how they shaped his work for the president.

WASHINGTON POST, CARLOS LOZADA

HATEMONGER: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist Agenda

By Jean Guerrero. William Morrow. 323 pp. $28.99

One of the few White House aides who has lasted the full term, Stephen Miller still wields influence over a policy arena that President Trump considers vital to his legacy. He is the “architect” of Trump’s restrictive immigration policies, and his “mind meld” with the president has produced executive orders and rhetoric heavy on exclusion, cruelty and “prejudicial white patriotism,” journalist Jean Guerrero argues in “Hatemonger,” her timely study of this White House survivor.

She makes clear how right-wing and nationalistic media personalities provided Miller the platform and tactics to hone his political vision — and theirs — and continued shaping his views during his time as a Senate aide and as a Trump adviser.

ATLANTIC Growing up in the so-called People’s Republic of Santa Monica as the son of well-off Jewish Democrats—his father was a lawyer and real-estate investor, his mother a homemaker—Miller was uninitiated in conservative thought. [Until he inadvertently came upon Guns & Ammo, which] led him to Wayne LaPierre’s book Guns, Crime, and Freedom, which he devoured, enraptured by the blunt force of the author’s prose. (“Clearly, the Warsaw ghetto stands in history as a shining example of the dangers of gun control.”)

WASHINGTON POST, CARLOS LOZADA

Guerrero dwells on [these] years in Santa Monica, Calif., where he grew up crossing the Mexican border for family vacations, eating meals cooked by Latin American housekeepers and attending school with Mexican American children. His confrontations started early. “As a boy, Miller waged an ideological war on his dark-skinned classmates,” Guerrero writes.

ATLANTIC Miller’s youthful political reinvention was also a puckish reaction to his surroundings. In the beachside bubble of liberal affluence where he was raised, people saw themselves as proud citizens of a progressive utopia. There were festivals celebrating multiculturalism, and “racial-harmony retreats” for students. Yet there were also tensions around racial and class inequality. Jason Islas, a progressive activist who was friends with Miller when they were kids, says it was the kind of place where wealthy white liberals would “conspicuously celebrate diversity in very self-congratulatory ways”—and then avert their eyes from the problems in their own community.

WASHINGTON POST, CARLOS LOZADA

In the summer after middle school, he informed a classmate that they could no longer be friends because of the boy’s Latino heritage. At his liberal high school, Miller admonished Mexican American students to “speak only English.” He worried that a Chicano student group wanted to reclaim California. “Racism does not exist,” he told school district committee on equality. “It’s in your imagination.” He fought against bilingual education, Spanish-language school announcements and Cinco de Mayo celebrations. In his most infamous early moment, he argued at an assembly that students should not have to pick up after themselves “when we have plenty of janitors who are paid to do it for us.”

Miller was, in essence, a troll, triggering the libs long before anyone called it that. “He was born with an ability to bring out anger from people,” a former counselor at the high school tells Guerrero, “and he rejoiced in that, it made him powerful.”

Guerrero drops tantalizing suggestions about Miller’s motivations. For instance, he complained to a childhood friend that one of his Latina housekeepers was “kind of emotionally abusive,” and he fretted about being dropped off at school in a housekeeper’s “junky” car, which made him “look poor.” Guerrero is persuasive when she notes that Miller’s childhood was a time of right-wing, anti-immigrant ferment in California.

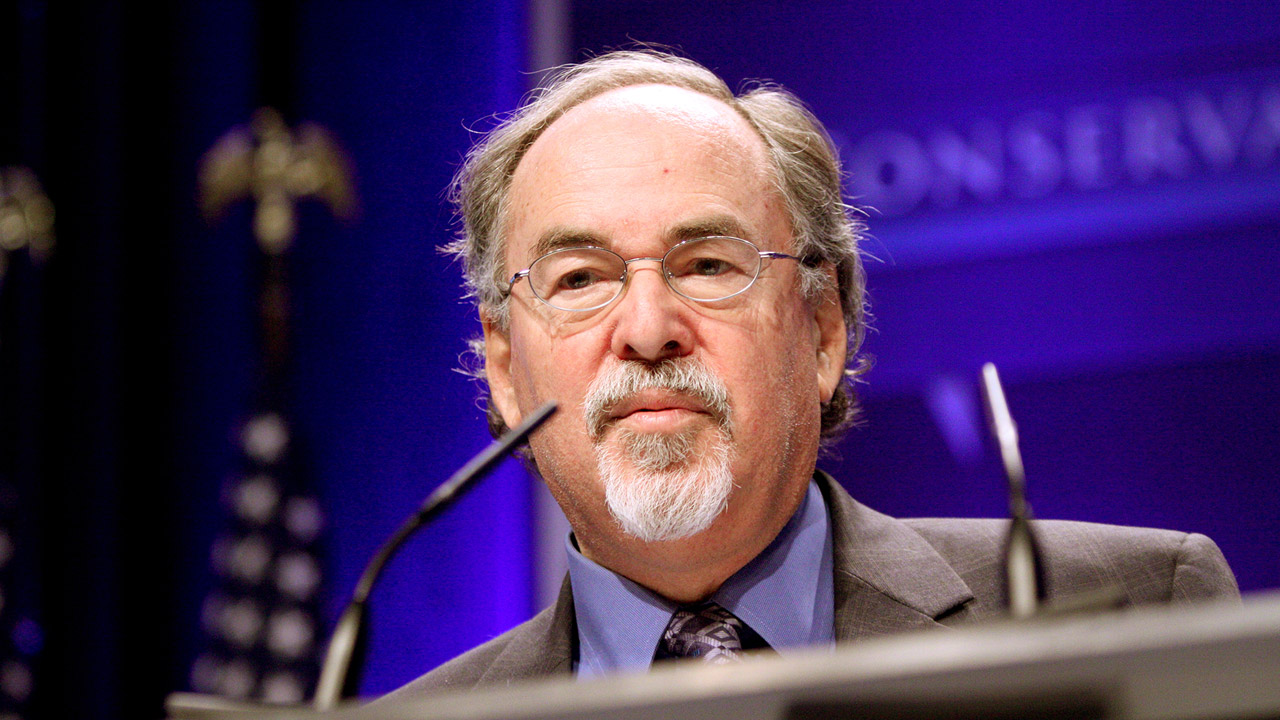

When Miller was in elementary school, Proposition 187 passed, prohibiting undocumented immigrants from accessing non-emergency state services, including public school. (It was later declared unconstitutional.) A teenage Miller, a fan of Rush Limbaugh’s 1992 book, “The Way Things Ought to Be,” started making radio appearances on the conservative “Larry Elder Show,” complaining about his high school. There he caught the attention of right-wing activist David Horowitz, [below] an ex-Marxist seeking to subvert the old lefty counterculture by teaching its tools to young right-wingers: how to attract media attention, stage controversial events and shame administrators who refused to “increase the scope of intellectual diversity” with conservative perspectives.

“In the 1970s, students started a political revolution on campus,” Miller wrote in an essay on Horowitz’s website, while still in high school. “Now is the time for a counter-revolution — one characterized by a devotion to this nation and its ideals.” He would become a Horowitz protege, and years later, Guerrero writes, the provocateur “would play a significant role in Trump’s campaign, with Miller as his vehicle.”

ATLANTIC : After 9/11, he emerged as a vociferous defender of the Bush administration, writing op-eds that compared students who opposed U.S. military actions to terrorists and concluding, “Osama Bin Laden would feel very welcome at Santa Monica High School.” During his junior year, he agitated for the school to lead regular recitals of the Pledge of Allegiance—and when his demand wasn’t met, he went on local talk radio to kick up some controversy. The tactic worked, and the school eventually acquiesced.

As an undergraduate at Duke University, Miller invited Horowitz to speak on campus, and he organized an immigration debate featuring Peter Brimelow, author of “Alien Nation: Common Sense About America’s Immigration Disaster.” The event was a “life-changing” experience for Miller, Guerrero writes, making him think more broadly about immigration, creating a framework for his initial instincts. In the 1995 book, Brimelow argued that the Statue of Liberty is not a symbol of immigration because the Emma Lazarus poem was only added to the pedestal years later; Miller would make the same argument in the White House press room in 2017.

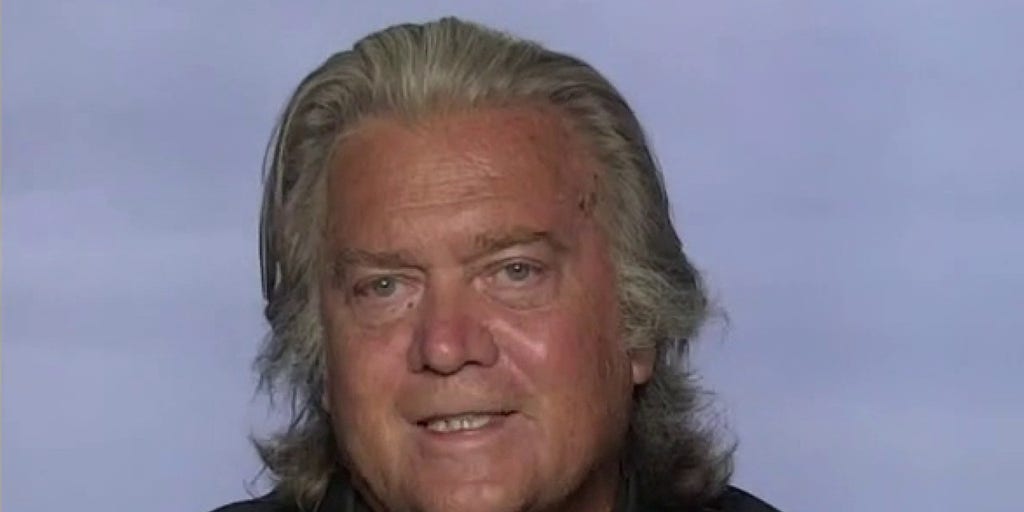

After Miller graduated from Duke, Horowitz helped him get a job as press aide for Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.) and later Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.), whose restrictive views on immigration dovetailed with Miller’s. On Capitol Hill, Miller gained a reputation as “vindictive” and a “street fighter,” but he also immersed himself in the details of immigration policy, absorbing statistics from prominent restrictionist think tanks. It was through Sessions that Miller met Bannon, and the three discussed the possibilities of a populist nationalist movement built on White voters — the opposite of the lesson the GOP establishment had drawn from Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential defeat.

Horowitz lurked behind the scenes, encouraging Sessions and Miller to counter the Democrats’ emotional social-justice appeals with “an equally emotional campaign that puts the aggressors on the defensive; that attacks them in the same moral language.” Fear, he argued, beats hope. Then Trump appeared, spouting crude versions of Miller’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. Fear was in the air, and soon, thanks to Bannon’s intercession, Miller was in the Trump campaign.

Miller’s backstory has been well reported (Guerrero often cites McKay Coppins’s 2018 Atlantic profile), as has his role in developing Trump’s immigration policies (the 2019 book “Border Wars” by Julie Hirschfeld Davis and Michael Shear details his efforts to exert total control over immigration policy by intimidating career Homeland Security officials). Guerrero’s contribution centers on how Miller’s early patrons retained their [influence.]

In May 2016, Miller emailed Horowitz, asking, “What are some ways the government and the oligarchs who rely on the government have ‘rigged’ the system against poor young blacks and hispanics?” Horowitz replied with multiple links, explaining that “the inner cities are war zones. . . . BLM [Black Lives Matter] makes criminals into martyrs.” The ideas soon appeared in a Trump campaign speech: “You can go to war zones in countries that we are fighting and it is safer than living in some of our inner cities that are run by the Democrats,” the candidate declared.

Later, Miller asked for help again: “The boss is doing a speech on radical Islam. What would you say about Sharia Law?” Horowitz responded that Islamic law is incompatible with the Constitution, adding that “referring to it as ‘Radical Islam’ — though inaccurate — is a good and necessary idea.” When Trump gave a speech attacking Hillary Clinton for not criticizing “radical Islamic terrorism,” Horowitz noticed. “Great f---ing ground-breaking speech,” he emailed Miller. “I spent the last twenty years waiting for this.”

At times, even his mentors worried that Miller and Trump were overdoing things. Horowitz suggested that accusing Barack Obama of founding the Islamic State was a distraction to the campaign. And Elder, [above] who encouraged his old radio guest to emphasize the national security risks of immigration — “we lack the ability to vet Muslim immigrants,” he wrote Miller during the campaign — argued that Trump’s attack on the loyalties of an American judge of Mexican descent went too far. (Both Horowitz and Elder shared these email exchanges with Guerrero.)

In the White House, Miller has gravitated toward his own preferred messages, usually revolving around brutal, fearmongering imagery of dangerous, criminal immigrants. That “gut-punching emotion,” Guerrero writes, “spiraling up from the underbelly of conservative media and a shared obsession with violent fantasies,” is a signature element of Trump and Miller’s worldview.

The mutual reinforcement between Trump World and conservative media is a constant refrain in coverage of this presidency. In “Hatemonger,” Guerrero makes such connections plain. And so does Miller. After Horowitz congratulated him on Trump’s “ground-breaking” campaign speech, Miller responded: “Thanks! Keep sending ideas.”

Carlos Lozada is author of the forthcoming “What Were We Thinking: A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era.”