Democrats, led by presidential nominee Joe Biden, denounced Trump’s actions as revelations from Bob Woodward’s book fueled a sense of outrage.

-

Trump’s comments came hours after excerpts from the book and audio of some of the 18 separate interviews he conducted with the author were released, fueling a sense of outrage over the president’s blunt description of knowing that he was not telling the truth about a virus that has killed nearly 190,000 Americans.

Democrats, led by presidential nominee Joe Biden, denounced Trump’s actions as part of a deliberate effort to lie to the public for his own political purposes when other world leaders took decisive action to warn their people and set those nations on a better path to handling the pandemic.

“He knew and purposely played it down. Worse, he lied to the American people. He knowingly and willingly lied about the threat it posed to the country for months,” Biden said in front of the United Auto Workers training facility in Warren, Mich., where he delivered a speech on a “Made in America” plan for the economy.

Biden called Trump’s actions “a life and death betrayal of the American people.”

Trump said publicly that he did nothing wrong.

“So the fact is, I’m a cheerleader for this country. I love our country. And I don’t want people to be frightened,” Trump told reporters at the White House after announcing his potential Supreme Court nominees if he wins reelection. “I don’t want to create panic, as you say. And certainly, I’m not going to drive this country or the world into a frenzy. We want to show confidence. We want to show strength.”

Trump says he knew coronavirus was ‘deadly’ and worse than the flu while intentionally misleading Americans

Despite this comment, Trump would spend another month comparing the coronavirus to the flu, arguing that since we don’t shut down society for the flu, we shouldn’t do it for the coronavirus. He invoked the flu comparison on Feb. 26, 27 and 28 and on March 2, 4, 6, 9 and 10, before ultimately admitting in late March, after adopting stricter safeguards recommended by health officials, that “it’s not the flu; it is vicious.”

That time period also brings an important new revelation from Woodward’s book. After Trump finally embraced those tougher measures March 16, he told Woodward that the nearly two months he had spent downplaying the virus were intentional.

“I wanted to always play it down,” Trump said March 19. He added: “I still like playing it down, because I don’t want to create a panic.”

The comments in Woodward’s book are nearly impossible to square with what Trump was saying at crucial junctures early in the outbreak. If he truly knew this was a far different situation than the flu, why would he keep comparing the two? If he truly knew the scope of the potential disaster ahead, why would he focus almost exclusively on downplaying it?

Avoiding “panic” is one thing, but leaving people with a false sense of security and risking them being underprepared is quite another. Trump certainly erred in that direction — and apparently deliberately so.

I’ve said from early in the outbreak that Trump’s M.O. seemed to be much more focused on avoiding momentary bad headlines about the situation — a trend that has characterized much of his presidency — than on truly combating it. When case numbers began to rise, Trump wrongly assured Americans that they’d soon drop. When the stock market began to drop, Trump seemed to fear that it would irreparably harm his silver bullet in the 2020 campaign: the economy.

As I also noted way back then, though, the danger for Trump — and the country — was much more in the long-term course of the outbreak than brief downturns in the markets. But Trump seemed to have an almost visceral reaction to the idea that the situation was dire or even just bad. That could be either because he believed it would personally reflect upon him, because he worried about strict measures to combat it damaging the economy in the months before his reelection campaign, or both.

The revelations Wednesday suggest that this was indeed a deliberate effort, rather than simply a president who was so utterly out of tune with his own health officials. Trump may not have bought his own hype in the way it appeared, but that doesn’t mean that lots of Americans — and especially Republicans — didn’t do so.

The newly reported comments, though, suggest that something more than optimism was lurking behind Trump’s early handling of the coronavirus outbreak. They suggest that he deliberately sought to give people a false sense of security. Even if you could perhaps argue that it was a well-intentioned effort to avert “panic” — and that’s a big if at this point, given Trump’s apparent fear of an economic downturn — it means that Trump, by his own admission, wasn’t really leveling with the American people about a life-or-death matter.

President Trump’s head popped up during his top-secret intelligence briefing in the Oval Office on Jan. 28 when the discussion turned to the coronavirus outbreak in China.

“This will be the biggest national security threat you face in your presidency,” national security adviser Robert C. O’Brien told Trump, according to a new book by Washington Post associate editor Bob Woodward. “This is going to be the roughest thing you face.”

Matthew Pottinger, the deputy national security adviser, agreed. He told the president that after reaching contacts in China, it was evident that the world faced a health emergency on par with the flu pandemic of 1918, which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

Ten days later, Trump called Woodward and revealed that he thought the situation was far more dire than what he had been saying publicly. “You just breathe the air and that’s how it’s passed,” Trump said in a Feb. 7 call. “And so that’s a very tricky one. That’s a very delicate one. It’s also more deadly than even your strenuous flus. This is deadly stuff,” the president repeated for emphasis.

Trump never did seem willing to fully mobilize the federal government and continually seemed to push problems off on the states,” Woodward writes. “There was no real management theory of the case or how to organize a massive enterprise to deal with one of the most complex emergencies the United States had ever faced.”

Woodward questioned Trump repeatedly about the national reckoning on racial injustice. Woodward asked the president about White privilege, noting that they were both White men of the same generation who had privileged upbringings. Woodward suggested that they had a responsibility to better “understand the anger and pain” felt by Black Americans.

“No,” Trump replied, his voice described by Woodward as mocking and incredulous. “You really drank the Kool-Aid, didn’t you? Just listen to you. Wow. No, I don’t feel that at all.”As Woodward pressed Trump to understand the plight of Black Americans after generations of discrimination, inequality and other atrocities, the president kept answering by pointing to economic numbers such as the pre-pandemic unemployment rate for Blacks and claiming, as he often has publicly, that he has done more for Blacks than any president except perhaps Abraham Lincoln.

In another conversation about race, on July 8, Trump complained about his lack of support among Black voters. “I’ve done a tremendous amount for the Black community,” he told Woodward. “And, honestly, I’m not feeling any love.”

When they spoke about race relations on June 22, when Woodward asked Trump whether he thinks there is “systematic or institutional racism in this country. Well, I think there is everywhere,” Trump said. “I think probably less here than most places. Or less here than many places.”

Asked by Woodward whether racism “is here” in the United States in a way that affects people’s lives, Trump replied: “I think it is. And it’s unfortunate. But I think it is.”

Trump shared with Woodward visceral reactions to several prominent Democrats of color. Upon seeing a shot of Sen. Kamala D. Harris of California, now the Democratic vice-presidential nominee, calmly and silently watching him deliver his State of the Union address, Trump remarked: “Hate! See the hate! See the hate!” Trump used the same phrase after an expressionless Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) appeared in the frame.

Trump was dismissive about former president Barack Obama and told Woodward that he was inclined to refer to him by his first and middle names, “Barack Hussein,” but wouldn’t in his company, to be “very nice.”

“I don’t think Obama’s smart,” Trump told Woodward. “I think he’s highly overrated. And I don’t think he’s a great speaker.” Trump added that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un thought Obama was “an asshole.”

Trump was taken with Kim’s flattery, Woodward writes, telling the author pridefully that Kim had addressed him as “Excellency.” Trump remarked that he was awestruck meeting Kim for the first time in 2018 in Singapore, thinking to himself, “Holy shit,” and finding Kim to be “far beyond smart.” Trump also boasted to Woodward that Kim “tells me everything,” including a graphic account of Kim having his uncle killed.

In the midst of reflecting upon how close the United States had come in 2017 to war with North Korea, Trump revealed: “I have built a nuclear — a weapons system that nobody’s ever had in this country before. We have stuff that you haven’t even seen or heard about. We have stuff that Putin and Xi have never heard about before. There’s nobody — what we have is incredible.”

Woodward writes that anonymous people later confirmed that the U.S. military had a secret new weapons system, but they would not provide details, and that the people were surprised Trump had disclosed it.

The book documents private grumblings, periods of exasperation and wrestling about whether to quit among the so-called adults of the Trump orbit: Mattis, Coats and then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson.

Mattis quietly went to Washington National Cathedral to pray about his concern for the nation’s fate under Trump’s command and, according to Woodward, told Coats, “There may come a time when we have to take collective action” since Trump is “dangerous. He’s unfit.”

Then-director of national intelligence Daniel Coats at a White House news briefing on Aug. 2, 2018. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

In a separate conversation recounted by Woodward, Mattis told Coats, “The president has no moral compass,” to which the director of national intelligence replied: “True. To him, a lie is not a lie. It’s just what he thinks. He doesn’t know the difference between the truth and a lie.”

Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law and senior adviser, is quoted by Woodward as saying, “The most dangerous people around the president are overconfident idiots,” which Woodward interprets as a reference to Mattis, Tillerson and former National Economic Council director Gary Cohn.

Kushner was a frequent target of ire among Trump’s Cabinet members, who saw him as untrustworthy and weak in dealing with heads of states. Tillerson found Kushner’s warm dealings with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu “nauseating to watch. It was stomach churning,” according to Woodward.

Kushner is quoted extensively in the book ruminating about his father-in-law and presidential power. Woodward writes that Kushner advised people that one of the most important guiding texts to understand the Trump presidency was “Alice in Wonderland,” a novel about a young girl who falls through a rabbit hole. He singled out the Cheshire cat, whose strategy was endurance and persistence, not direction.

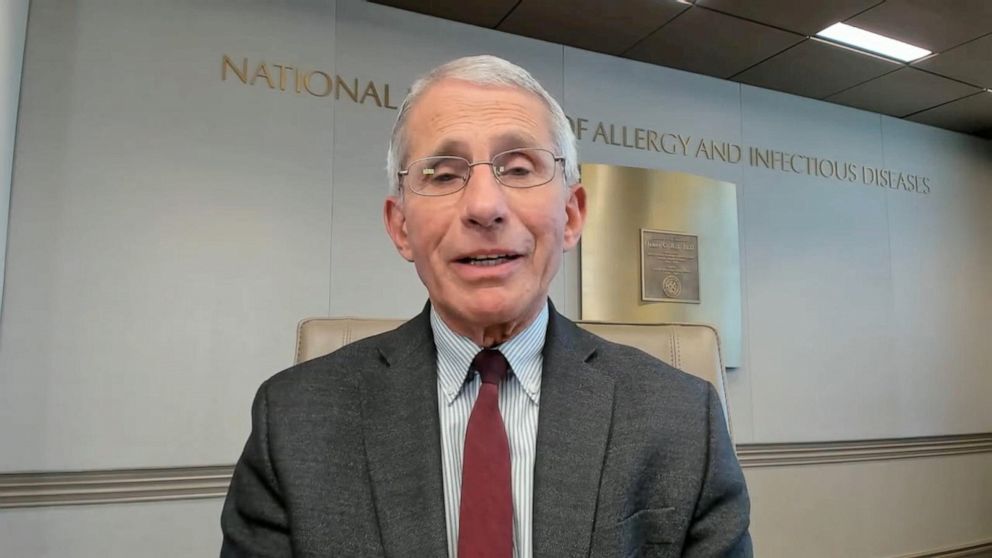

Fauci at one point tells others that the president “is on a separate channel” and unfocused in meetings, with “rudderless” leadership, according to Woodward. “His attention span is like a minus number,” Fauci said, according to Woodward. “His sole purpose is to get reelected.”

In one Oval Office meeting recounted by Woodward, after Trump had made false statements in a news briefing, Fauci said in front of him: “We can’t let the president be out there being vulnerable, saying something that’s going to come back and bite him.” Pence, Kushner, Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and senior policy adviser Stephen Miller tensed up at once, Woodward writes, surprised Fauci would talk in front of Trump that way.

Woodward describes Fauci as particularly disappointed in Kushner for talking like a cheerleader as if everything was great. In June, as the virus was spreading wildly coast to coast and case numbers soared in Arizona, Florida, Texas and other states, Kushner said of Trump, “The goal is to get his head from governing to campaigning.”

The president said he did this to avoid “panic” and a “frenzy," admitting a central revelation in the forthcoming book, “Rage,” by Washington Post associate editor Bob Woodward. “Trump’s comments came hours after excerpts from the book and audio of some of the 18 separate interviews he conducted with the author were released, fueling a sense of outrage over the president’s blunt description of knowing that he was not telling the truth about a virus that has killed nearly 190,000 Americans," Josh Dawsey, Felicia Sonmez and Paul Kane report. "Privately, however, the president realized the book would not be good for him politically. For weeks, he told advisers that Woodward’s book was likely to be negative … But the White House had done little to prepare for it, officials said. Initially, surrogates received bland talking points that included comments from White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany’s Wednesday briefing. In a phone interview with Fox News’s Sean Hannity on Wednesday night, Trump was dismissive of the book. [He said he's too busy to read it.] …

“Trump encouraged others to speak with Woodward and would often mention the journalist in conversations with other advisers, suggesting that he might call him again. Some of the conversations between the two men, a White House official said, were precipitated by Trump — who thought Woodward was more receptive to a favorable narrative about his presidency. There was widespread finger-pointing in Trump’s orbit Wednesday about the book and its revelations, but some advisers noted that Trump is the one who drove the decision to cooperate. … In a familiar routine on Capitol Hill, Republicans ducked from the latest Trump controversy, almost uniformly asserting they had yet to read Woodward’s book."

Woodward was criticized for not revealing Trump’s comments earlier. “Woodward said his aim was to provide a fuller context than could occur in a news story: ‘I knew I could tell the second draft of history, and I knew I could tell it before the election,'” writes media columnist Margaret Sullivan. "What’s more, he said, there were at least two problems with what he heard from Trump in February that kept him from putting it in the newspaper at the time: First, he didn’t know what the source of Trump’s information was. … Second, Woodward said, ‘the biggest problem I had, which is always a problem with Trump, is I didn’t know if it was true.’ … Woodward said he believes his highest purpose isn’t to write daily stories but to give his readers the big picture. ... Woodward’s effort, he said, was to deliver in book form ‘the best obtainable version of the truth,’ not to rush individual revelations into publication.”

|

“The official, Brian Murphy, who until recently was in charge of intelligence and analysis at DHS, said in a whistleblower complaint that on two occasions he was told to stand down on reporting about the Russian threat and alleged that senior officials told him to modify other intelligence reports, including about white supremacists, to bring them in line with Trump’s public comments, directions he said he refused,” Shane Harris, Nick Miroff and Ellen Nakashima report. “On July 8, Murphy said in the complaint, acting homeland security secretary Chad Wolf told him that an ‘intelligence notification’ regarding Russian disinformation efforts should be ‘held’ because it was unflattering to Trump, who has long derided the Kremlin’s interference as a ‘hoax’ that was concocted by his opponents to delegitimize his victory in 2016. … DHS’s intelligence reports are routinely shared with the FBI, other federal law enforcement agencies, and state and local governments. Murphy objected to Wolf’s instruction, ‘stating that it was improper to hold a vetted intelligence product for reasons [of] political embarrassment,’ according to a copy of his whistleblower complaint. … “The president’s political interests were often of greater concern to senior leaders at the department than reporting the facts based on evidence, Murphy alleges. He claims that Wolf and Ken Cuccinelli, [above] the department’s second-in-command, on various occasions instructed him to massage the language in intelligence reports ‘to ensure they matched up with the public comments by Trump on the subject of ANTIFA and ‘anarchist’ groups,’ according to the complaint. … [Murphy] was removed from his position and assigned in July to an administrative role, where he remains. His new assignment followed reports by The Post that his office had compiled ‘intelligence reports’ about tweets by journalists who were covering protests in Portland, Ore. In his complaint, Murphy called press coverage of his office’s activities ‘significantly flawed.’ … Murphy’s complaint prompted mixed reactions among former senior administration officials, who said he had valid and significant concerns but described him as a flawed messenger. … The House Intelligence Committee has asked Murphy to testify later this month.” (Read Murphy's 24-page complaint here.)

“The president’s political interests were often of greater concern to senior leaders at the department than reporting the facts based on evidence, Murphy alleges. He claims that Wolf and Ken Cuccinelli, [above] the department’s second-in-command, on various occasions instructed him to massage the language in intelligence reports ‘to ensure they matched up with the public comments by Trump on the subject of ANTIFA and ‘anarchist’ groups,’ according to the complaint. … [Murphy] was removed from his position and assigned in July to an administrative role, where he remains. His new assignment followed reports by The Post that his office had compiled ‘intelligence reports’ about tweets by journalists who were covering protests in Portland, Ore. In his complaint, Murphy called press coverage of his office’s activities ‘significantly flawed.’ … Murphy’s complaint prompted mixed reactions among former senior administration officials, who said he had valid and significant concerns but described him as a flawed messenger. … The House Intelligence Committee has asked Murphy to testify later this month.” (Read Murphy's 24-page complaint here.)