Why the Amazon Deal Collapsed: A Tech Giant Stumbles in N.Y.

Amazon had promised to create more than 25,000 jobs on a new campus in Queens. On Thursday, it abruptly announced that it was canceling the deal.CreditBenjamin Norman for The New York Times

NY TIMES

A senior executive from Amazon, one of the world’s biggest companies, found himself last weekend in a showdown with a suburban state senator.

The executive, Brian Huseman, was trying to find out whether the New York state senator, Andrea Stewart-Cousins, would keep an obscure state board from blocking Amazon’s ambitious plans to expand in New York City.

It was the second phone call in two days between Mr. Huseman and Ms. Stewart-Cousins, who had just risen to power as Democratic majority leader, and once again, she tried to explain to him the politics of Albany.

Ms. Stewart-Cousins said in an interview that she told Mr. Huseman, “We just need to move on,” indicating that Amazon had to let the approval process run its course.

It was not the response that Amazon wanted.

For Amazon, long accustomed to highly deferential treatment from localities across the country, the phone call was a further indignity after weeks of relentless criticism from lawmakers, unions and progressive activists that the company feared was staining its reputation.

On Thursday, Amazon abruptly announced that it was canceling the deal, under which the company had promised to create more than 25,000 jobs on a new campus in Long Island City, Queens, in return for nearly $3 billion in government incentives.

An examination of the deal’s collapse showed that Amazon badly misjudged how it would be received in New York, apparently because the company has rarely ventured into such a raucous political arena as it has pursued a breakneck expansion in recent years.

This account was pieced together from dozens of interviews this week with government officials, Amazon representatives, lobbyists and others. Most spoke on the condition of anonymity to relay closed-door deliberations.

The company’s retreat capped several days of intense behind-the-scenes maneuvering between government officials and Amazon executives, including efforts by Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo to woo unions and Mayor Bill de Blasio to try to reach Jeff Bezos, the company’s chief executive.

On Monday, Mr. Cuomo and Mr. de Blasio, bitter rivals who had put aside their differences to mount a bid for an Amazon site, met in Albany to discuss how to pacify unions that had voiced strong objections to the company.

Mr. de Blasio then called a top executive in the company, seeking assurances that the deal was still on. The executive did not indicate that it was in trouble

On Wednesday, a senior Amazon executive in charge of real estate, John Schoettler, arrived from Seattle for a meeting convened by Mr. Cuomo in his Manhattan offices between Amazon and unions. By the end, the unions and the executives seemed to be making progress toward a resolution.

That night, the company decided internally to pull the plug.

The choice blindsided Mr. Cuomo and Mr. de Blasio.

“Out of nowhere, they took their ball and went home,” Mr. de Blasio said on Thursday night.

He learned of the decision in a phone call from Jay Carney, an Amazon vice president. Even as the deal was in peril, Mr. Carney, who oversees the company’s press and government relations, never went to New York to meet with officials, three people with knowledge of the meetings said.

Amazon can deliver toothpaste in traffic-snarled Manhattan on the same day an order is placed. But when it came to navigating the politics of New York, the company appeared out of step, a giant stumbling onto a political stage that — despite its data-driven success — it never fully understood.

“Amazon underestimated the power of a vocal minority and miscalculated how much it needed to engage with those audiences to make HQ2 a success,” Joseph Parilla, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, said, referring to the second headquarters search.

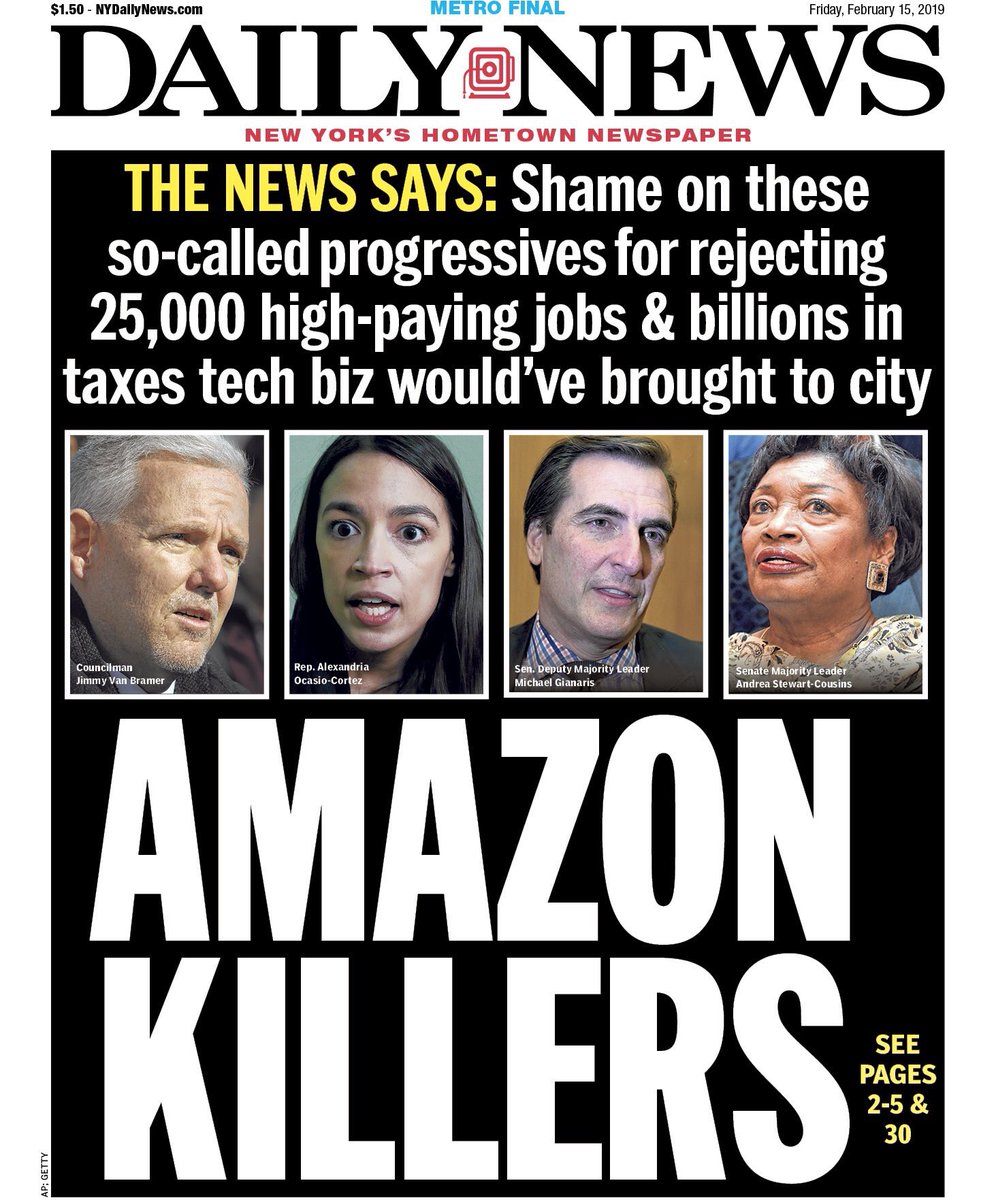

The company, in particular, failed to develop a robust strategy to address the growing influence of the progressive left in New York, led by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of Queens, who was elected in November and was a fervent skeptic of the deal.

The political winds changed so swiftly that local lawmakers in Queens who had signed a letter in 2017 trying to woo Amazon refashioned themselves as champions of the opposition in recent months.

Corey Johnson, the speaker of the City Council, refused repeatedly to even meet with Amazon representatives despite at least three requests. Mr. Johnson held hearings instead of the private meetings Amazon requested. Amazon met with 35 of the 51 council members, and more had been scheduled for this week. Mr. Johnson’s staff did meet with the company.

A spokeswoman for Amazon declined to comment for this article. But two people involved in internal discussions at Amazon said the company’s concerns were not primarily that the deal would fail to receive government approval. Executives were confident it would cross the finish line.

The company instead felt that, with little sign that the opposition was dissipating, it was staring down a decades-long commitment to a political climate in which everything the company did would be scrutinized.

“Amazon had to think about what a long-term relationship with New York City would look like, and based on the experiences with local and state politicians to date, concluded it would be difficult at best,” one of the people said.

Amazon executives involved in the negotiations said they were frustrated that the economic benefits of the project — a winning argument with many business leaders and some community members, failed to sway some officials.

“What we were hearing from people — small business owners, educators, community leaders — was completely different than what we were getting from the local elected officials,” said one of the people involved with the Amazon side.

Those feelings, and Amazon’s eventual retreat, were foreshadowed by testimony from Mr. Huseman last month at the City Council: “We were invited to come to New York,” he said, adding pointedly, “and we want to invest in a community that wants us.”

Instead, the company saw how its plans for Queens had become such a flash point that they turned into an issue in the Feb. 26 special election for public advocate, a citywide position with a big megaphone. Company officials worried that the debate over the project could drag on and become ensnared in the 2021 mayoral election, and beyond.

“In most places, people are just doing cartwheels and somersaults when Amazon comes in,” said Alex Pearlstein, vice president at Market Street Services, which helps cities attract employers. “New York just didn’t need them as bad as most places do.”

Amazon grew in Seattle for almost two decades with little civic engagement. Initially, most of its buildings were built by an outside developer. Neither Mr. Bezos, nor any Amazon executive, attended the groundbreaking ceremony for its headquarters that the mayor and governor threw.

By about 2015, as Amazon was developing its own buildings, and with roughly 25,000 employees in Washington State, it started engaging more, albeit slowly.

A top real estate executive chaired the local Chamber of Commerce, and it began forging relationships with two local nonprofits, one that works with homeless families and another job training program for the restaurant industry.

Yet even as housing costs soared in the booming city, Amazon did not take public positions in debates over how to alleviate the affordability crunch. It largely saw its role as creating high-paying jobs, and the city’s job to accommodate them.

So last year, when Amazon said it might halt its growth locally if the city approved a tax on large employers to fund homeless services and low-income housing, it sent a shock throughout Seattle. The city was not accustomed to the company playing hardball, let alone commenting on politics.

The trouble in New York City began last year with a hostile City Council hearing in December, and then another last month.

The company endured hours of attacks on its plans to come to New York, and on its business practices — particularly its stance against unions — in general. Protesters heckled. Council members forced an Amazon official to declare the company’s anti-union stance on the record.

The moment resonated for executives: Amazon was not accustomed to being forced to respond publicly on its policies and operations.

A turning point came on Feb. 4, when Ms. Stewart-Cousins, the new Democratic leader in the State Senate, selected Mr. Gianaris, the state senator and one of Amazon’s most vocal opponents, to the board with the power to block the deal. It was clear the opposition would not go away soon.

Mr. Cuomo could refuse to appoint Mr. Gianaris, of Queens. But the company wanted to know: What would happen then?

So on Feb. 8 and then again on Feb. 9, Amazon’s representatives spoke on the phone with Ms. Stewart-Cousins.

She told the company’s representatives that Mr. Cuomo was planning to reject Mr. Gianaris. But she could not say precisely what would happen next, the people said. Who would be named in his place?

Amazon wanted certainty that the next person selected would not be a roadblock: The fate of its campus could not hang on the whims of an unnamed state senator on a board — the Public Authorities Control Board — that few could name.

She did not offer any guarantees, but thought the Senate and the company would be able to work together.

“Obviously, the Legislature would have a role to play,” she said in an interview.

The next time she heard from Mr. Huseman was Thursday, just as Amazon announced that the deal was dead.

•

•